Earlier this month, the Labor Department revealed that America’s unemployment had fallen to its lowest level since 1969. President Trump proceeded to declare that he was now presiding over “the greatest economy in the HISTORY of America” — and a bitter debate over whether Trump had truly made the economy “great again.”

This argument centered on two distinct questions:

1) Is the economy actually great?

2) To the extent that the economy is great, is said greatness a product of Trump’s wise leadership?

The second question is easier answer than the first. There is essentially no evidence that the president’s tax cuts (his sole piece of major economic legislation) did anything to significantly improve America’s macroeconomic performance. Since that legislation’s passage, economic growth in the U.S. has actually slowed; consumer spending and wage growth has been tepid; and business investment, unremarkable.

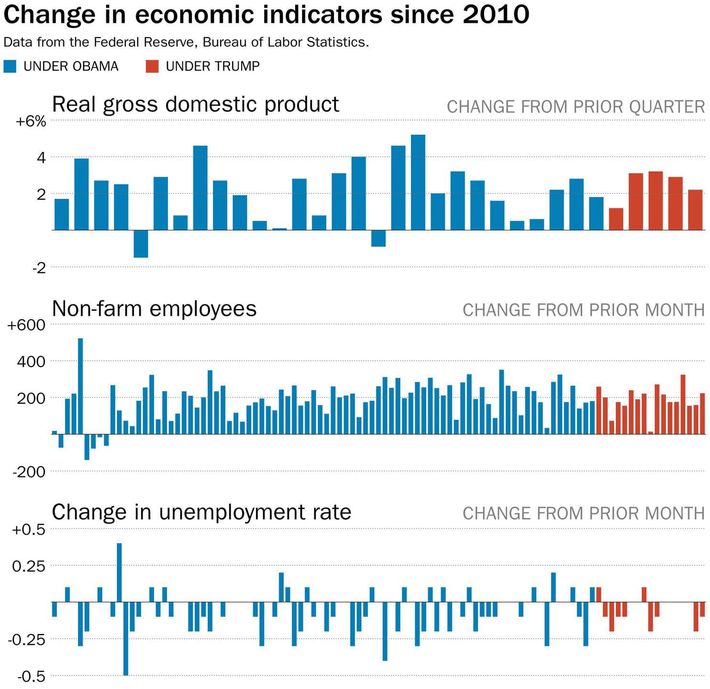

One can reasonably credit Trump for successfully avoiding any policy mistake disastrous enough to derail the expansion he inherited (a preemptive war with North Korea, for example). But his entrance into the Oval Office did not coincide with any significant, positive change in the economy’s preexisting trend line. If you do not own a pass-through business or a significant amount of corporate stock, chances are Trump has personally done nothing to significantly improve your economic circumstances.

Whether the Trump economy has been “great” is a more subjective matter. By most measures, it is better now than when Trump took office; and by some, it is exceptionally strong. The overall unemployment rate is the lowest it’s been in decades; the African-American unemployment rate is the lowest in recorded history; and the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers is the lowest it’s been since the government starting tracking that statistic in December 2000.

On the other hand, Americans are deeply indebted, many are stuck with part-time jobs, and wage gains have been so disappointing, their weakness has challenged fundamental premises of mainstream economics: Simply put, you aren’t supposed to be able to pay workers this little when the unemployment rate is this low.

And on Tuesday, the big picture on Americans’ paychecks grew even darker: In May, U.S. inflation accelerated to its fastest pace in more than six years — and wiped out what little wage growth the typical American worker had seen over the past 12 months in the process.

The consumer price index was 2.8 percent higher this past pay May than it was the same month one year ago; that increase leaves real average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers (a.k.a. the vast majority of workers) 0.1 percent lower than they were 12 months ago.

Notably, while wage growth was infamously tepid during the Obama years, the low-inflation environment of 2015 and 2016 did allow ordinary workers to secure real raises. Part of the uptick in inflation this year is a product of rising oil prices, a phenomenon over which the American president has little control. But some of it is likely attributable to the deficit expansion that Trump used to finance his regressive tax cuts. (To the extent that is the case, ordinary workers are effectively paying for the price for the Koch brothers’ big payday).

Regardless, the fact that workers aren’t seeing any real wage gains — at (somewhere near) the peak of an economic expansion — is a crisis. The share of growth that goes to labor (as opposed to capital) has declined substantially in recent decades. If workers can’t secure a bigger slice of the economic pie at a time of 3.8 percent unemployment, when can they?

That is a genuinely hard question. But it seems reasonable to guess that Americans will not see truly significant wage gains, so long as their president continues to do everything in his power to reduce their leverage over their bosses.