Last week, a 28-year-old socialist — who had campaigned on a call to abolish Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) — defeated the chairman of the House Democratic caucus in a primary election.

Republican operatives promptly salivated: For decades, GOP candidates had been leveling attacks against a fictional Nancy Pelosi, one who supported “open borders” and “collectivism.” Now, they could attack the actual Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — and cast this feminist, socialist, “globalist” radical as the true face of today’s Democratic Party; the one that “real Americans” in the heartland didn’t need to leave — because the party had already left them.

Unsurprisingly, Democratic leaders scrambled to distance their party’s national brand from the one that had just prevailed in the Bronx. “They made a choice in one district,” Pelosi told reporters last week. “So let’s not get yourself carried away.”

On Sunday, Illinois senator Tammy Duckworth told CNN that, while Ocasio-Cortez was “the future of the party in the Bronx, where she is … I think that you can’t win the White House without the Midwest and I don’t think you can go too far to the left and still win the Midwest.”

Ocasio-Cortez begged to differ.

And they’re both probably right.

Certain aspects of Ocasio-Cortez’s campaign were tailored to an electorate of working-class Bronxites, and young, highly educated gentrifiers (who are, for the moment, one of the core constituencies for far-left politics in the U.S.). Democratic candidates in heavily white, rural swing districts probably wouldn’t benefit by adopting the slogans “abolish ICE” and “democratic socialism.” Those phrases are radical, by design; their purpose is to galvanize activist energy — and expand the boundaries of political possibility — by articulating a vision of transformative change. And they’ve proven quite effective at serving those functions.

But they aren’t optimal slogans for the Democratic Party in heavily white, nonurban swing districts — and were never meant to be.

“Abolish ICE” either means an end to all internal immigration enforcement (a very reasonable idea, but one that will sound unreasonable, at least at first, to many voters that Democrats need to win this fall), or else, a progressive reorganization of the federal government’s immigration-enforcement bureaucracy (an idea that will sound very boring to many voters that Democrats need to win this fall).

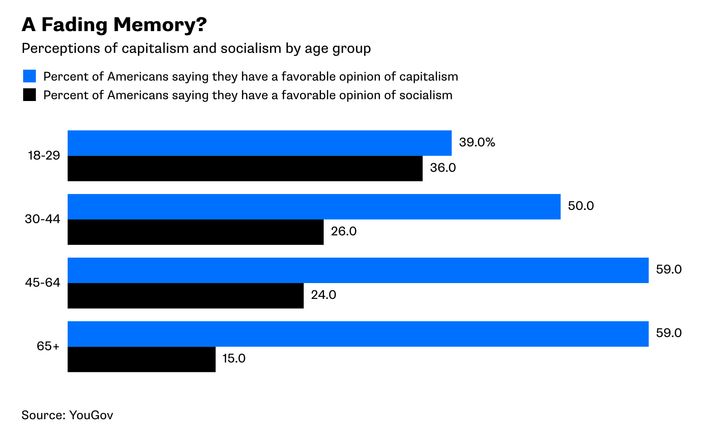

Meanwhile, although socialism is coming back into fashion among the young, that word’s approval rating is still lower than Donald Trump’s with voters over 30.

And yet, if some of the signifiers of Ocasio-Cortez’s politics are too “far left for the Midwest,” there’s little reason to believe that the substance of her politics is. Republicans might have the upper hand in a fight over abstractions like “socialism” or the “abolition of internal immigration enforcement.” But it’s far from clear that Democrats would lose an argument over the virtues of Ocasio-Cortez’s policy platform — even before a “Midwest” audience.

Both Medicare for All and single-payer health care enjoy majority support in recent polling from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Data for Progress (DFP), a progressive think tank, used demographic information from Kaiser’s poll to estimate the level of support for Medicare for All in individual states. Its model suggests that, in a 2014 turnout environment — which is to say, one that assumes higher turnout for Republican constituencies — a majority of voters in Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania would all support a socialist takeover of the health-insurance industry (so long as you didn’t put the idea to them in those terms).

Now, it is true that support for Medicare for All is malleable when pollsters introduce counterarguments. But even if we stipulate that support for the policy is somewhat weaker than it appears, there is little doubt that any Democrat running on Medicare for All in a purple district will have a more mainstream position on health-care policy than the national Republican Party. Polls consistently find that an overwhelming majority of the American public — one that includes most Republican voters — supports higher federal spending on health care, and opposes cuts to Medicaid (just 12 percent of the public supports cutting that program). Every major GOP health-care plan introduced in the past decade runs counter to those preferences; the ones introduced in the last year would have slashed Medicaid spending by nearly $1 trillion.

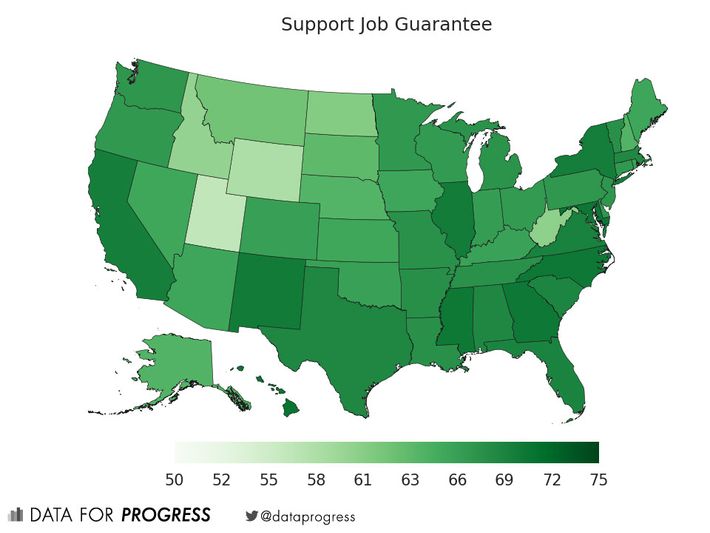

The most radical economic policy on Ocasio-Cortez’s platform — a federal job guarantee — meanwhile, actually polls quite well in “flyover country.” In a survey commissioned by the Center for American Progress, a supermajority of voters agreed that “for anyone who is unemployed or underemployed, the government should guarantee them a job with a decent wage doing work that local communities need, such as rebuilding roads, bridges, and schools or working as teachers, home health-care aides, or child-care providers.”

Critically, support for this premise was almost exactly as strong among rural-dwelling demographic groups as it was among urban ones: According to DFP’s modeling, CAP’s proposal boasts roughly 69 percent support in urban zip codes, and 67 percent in rural ones.

There are a lot of reasonable, technocratic objections to the job guarantee as a policy. But polling suggests that there is majoritarian support for a massive public-jobs program of some kind — and that framing said program as “guaranteed jobs” might be politically effective.

Other items on Ocasio-Cortez’s platform poll similarly well. A bipartisan majority of voters have espoused support for “breaking up the big banks” in recent years, while nearly 70 percent of Americans want the government to take “aggressive action” on climate change, according to Reuters/Ipsos.

“Housing as a human right” might sound radical, but in substance, it’s anything but: The Department of Housing and Urban Development believes it could end homelessness with an additional $20 billion a year in funding; other experts put that price tag even lower. I don’t think the question, “Should the government raise taxes for the rich by $20 billion, if doing so would end all homelessness in the U.S.?” has been polled, but I would be surprised if it didn’t poll well, even in the Midwest.

Similarly, on the question of immigration enforcement, Ocasio-Cortez’s position is likely more palatable when rendered in concrete terms than in abstract ones. Many white Midwesterners might recoil at phrases like “abolish ICE” or “open borders.” But if one asks the question, “Should the government concentrate its immigration-enforcement resources on combating violent criminals and gang activity, instead of going after law-abiding day laborers?” I suspect you’d find more support for the democratic socialist point of view.

The palatability of Ocasio-Cortez’s policy platform reflects two important realities: Actually existing “democratic socialism” — which is to say, the brand championed by its most prominent proponents in elected office — is almost indistinguishable from left-liberalism; and left-liberal policies are already quite popular in the United States.

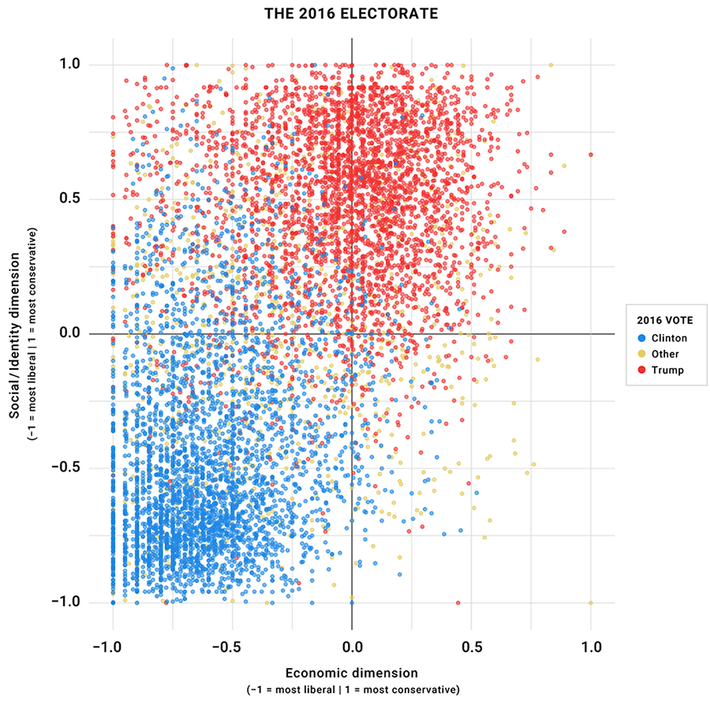

If all Americans voted for the party whose positions on economic policy best matched their own stated preferences, then the Republican Party would not be competitive in national elections. The GOP’s strength derives entirely from the considerable appeal of white identity politics with constituencies that happen to wield disproportionate power over our political system.

Thus, the key for Democrats — especially in the Midwest, where a lot of economically liberal, culturally conservative white voters live — is to increase the salience of class identity in American elections.

And a modified version of Ocasio-Cortez’s politics might actually be a good model for that endeavor. In her paid messaging and public oratory, the 28-year-old socialist relentlessly characterizes politics as a struggle between working people and unaccountable, corporate interests. In her justly celebrated campaign ad, Ocasio-Cortez never used the words “socialism” or “abolish ICE.” Instead, she established the authenticity of her connection to her district; name-checked some of the specific material anxieties and challenges facing the voters who live there (rising rents, foreclosure, gentrification); and then defined her race as one of “people versus money — we’ve got people, they’ve got money.”

Transporting this model from the Bronx to Macomb County would certainly require switching up the details. But there’s little reason to think that a customized version of Ocasio-Cortez’s class-centric, social-democratic politics can’t thrive in the Rust Belt.

All of which is to say: Tammy Duckworth should embrace “socialism with Midwestern characteristics.”