Brett Kavanaugh would make a perfectly normal Supreme Court justice. The appellate judge boasts all of the conventional credentials for that post (as his former professors at Yale Law will eagerly inform you). His jurisprudence, while markedly right-wing, is well within the conservative mainstream. As of this writing, he is not known for boasting about his affinity for grabbing women by their genitalia, or preying on seventh-grade girls in mall food courts, or abetting sexual abuse in wrestling team locker-rooms, or spending taxpayer money on “tactical pants” — or engaging in any of the other behaviors that have come to define abnormal Republicanism in the Trump era. On the contrary, Kavanaugh is, by most accounts, normcore to the core — a grade-A “carpool dad,” courteous mentor, and good friend to many an elite Washingtonian, pro-Trump and anti-Trump, alike.

Thus, when some progressives responded to Kavanaugh’s nomination to the high court by expressing despair for their democracy’s future, the right-flank of “the Resistance” cried foul. In their view, it was perfectly understandable for liberals to lament an ideological defeat — but equating that defeat with a democratic crisis was not. After all, Donald Trump’s tendency to do the latter is part of what makes him a threat to American democracy: to suggest that the other side’s policy victories are losses for the republic itself is to suggest that the maintenance of democracy requires its suspension. The Week’s Damon Linker offers a representative rendition of this critique:

[T]he liberal response to the Kavanaugh announcement … would seem to imply that the mainstream Democratic position has arrived at the point where it considers not just President Trump’s most egregious statements, behavior, and policies to be a truly alarming threat to liberal democracy in America — but longstanding, mainstream Republican positions an alarming threat, too.

…On this view, Republicans are less a perfectly legitimate rival for power than a civic menace — a formidable enemy that needs to be decisively defeated. It’s hard to see how the ordinary back-and-forth of democratic politics, with two or more parties trading or sharing power, can be allowed to continue when the prospect of the other side’s political victory could precipitate the end of the system itself.

…Do Democrats really intend to suggest that Americans need to agree with them or else risk subverting American democracy as such? If so, they should be clear about it — and honest with themselves about what it implies, which is that what was formerly considered perfectly normal (the ordinary give-and-take of democratic politics) has now become a luxury the country can no longer afford.

The problem with this analysis is simple: “mainstream Democrats” have come to view the Republican Party as a threat to democracy because the Republican Party has come to (correctly) view democracy as a threat to itself. For this reason, the idea that the GOP is a “civic menace” is perfectly reconcilable with a commitment to “the ordinary give-and-take of democratic politics.” While many progressives want to make structural changes to the American political system to reduce the probability of the GOP (as currently constituted) holding power, those changes are all aimed at making our electoral institutions more democratic, not less.

Linker misses this because he declines to engage with the substance of the left’s critique. Instead, he points to three tweets from left-of-center Twitter users (one from a prominent chronicler of climate change, two from Hollywood entertainers) and concludes from these that “mainstream” Democrats now believe opposition to gun control is tantamount to treason.

It is indisputably true that individual progressives do, on occasion, irresponsibly equate discrete conservative policy victories with democratic crises. But to the extent that there is a consensus among Democratic intellectuals and operatives that the Republican Party is no longer “a perfectly legitimate rival,” that view is rooted in the “normal” GOP’s myriad attempts to erode the possibility of popular sovereignty.

Normal Republicans are trying to disenfranchise Americans who do not agree with them.

These efforts fall into two categories. The first, and most alarming, consists of attacks on the formal mechanisms of democracy — on the capacity of eligible voters to cast their ballots, and on the ability of electoral majorities to translate their will into political power.

Long before Donald Trump’s foray into conservative politics, “mainstream Republicans” had already made restricting the franchise a top policy priority. On some fronts, the party has made this ambition explicit — Republican-controlled state governments have pushed to implement (or maintain) laws that disenfranchise former felons. In 2002, Mitch McConnell defended such measures by asserting, from the Senate floor, that “voting is a privilege.”

The GOP has been less forthright about its attempts to disenfranchise Americans who don’t have criminal records. Instead, it has pursued this aim under the pretense of concern for a crisis of mass voter fraud. George W. Bush’s (“normal, mainstream”) Republican administration launched a five-year investigation into this alleged crisis — one that produced “no evidence of any organized effort to skew federal elections.” Subsequent research into this matter has affirmed the Justice Department’s conclusion that “impersonation fraud” is all but nonexistent in American elections.

Had Republicans been sincerely concerned about such fraud, the discovery that it did not exist would have sapped their enthusiasm for passing “voter ID” laws (which reliably depress nonwhite voter participation); but they weren’t, so it didn’t.

In reality, the Republican Party has been pushing such measures because it would struggle to retain power if America’s large, nonvoting population — which is disproportionately young, low-income, and nonwhite — were to start regularly showing up at the polls. This claim is affirmed by public opinion data and demography, but also, on occasion, by Republican operatives themselves. Last year, the chairman of Montana’s Republican Party advised his co-partisans against holding a “mail-in” special election to replace outgoing House member Ryan Zinke because such an approach would enable too many Democrats to vote. In 2016, the executive director of North Carolina’s Republican Party sent an email urging the state’s (GOP-controlled) county election boards to restrict access to early voting, so as to benefit the GOP.

As the pool of eligible voters has grown less white, and more millennial, the task of customizing the electorate has become increasingly urgent for Republicans. This is most apparent in North Carolina, where the GOP-dominated state legislature has taken radical measures to insulate itself from the threat of an increasingly diverse and liberal electorate. There, “normal” Republicans have purged thousands of voters from the rolls; pushed to add a voter ID requirement into the state constitution; and passed a law aimed at making it prohibitively expensive for many counties to offer early voting (generally, increasing the availability of early voting increases African-American turnout).

Not content to merely reduce Democratic voter participation, state-level Republican parties have also worked to dilute the influence of those Democratic voters who do happen to make it to the polls through aggressive, partisan gerrymandering. To be sure, such biased district-drawing is a bipartisan enterprise — and, because the Republican coalition is more geographically disparate than the Democratic one (which is heavily concentrated in urban areas), the former would enjoy disproportionate power in House elections, even with “nonpartisan” maps (conventionally defined, anyway). Nevertheless, the key point is that, in the present context, the GOP has a deep investment in the survival of extreme forms of partisan gerrymandering, while Democrats are more than happy to dispense with such distortions of the popular will. What’s more, the GOP’s attempts to minimize the power that Democrats can secure by winning a majority of the vote extends well beyond partisan redistricting; in the Tarheel State, it has also involved systematically limiting the power of offices that the Democratic Party happens to win.

“Normal” Republican Supreme Court justices have played an indispensable role in these assaults on formal democracy. The Roberts court’s evisceration of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — which is to say, of voting protections that the GOP had failed to repeal through democratic means — was a precondition for many of the Republican Party’s state-level assaults on African-American voting rights. Meanwhile, the conservative justices’ (perhaps, more defensible) refusal to put any limitations on partisan gerrymandering has further abetted the GOP’s attempts to consolidate minority rule.

Brett Kavanaugh’s jurisprudence demonstrates that he shares the “mainstream Republican positions” that led his fellow conservative jurists to abet voter suppression. And his taste in judicial heroes suggests that he does not consider protecting African-Americans’ civil rights to be a very important part of the Supreme Court’s mission.

Progressives aren’t the ones who believe that America “can’t afford” to allow Republican voters to elect a government that enacts their preferences — GOP elites like Brett Kavanaugh are.

In addition to its attacks on the formal institutions of democracy, the GOP has also sought to erode the substance of self-government. It has done this, chiefly, by working to insulate the policy preferences of the economic elite from popular rebuke — despite the fact that a majority of Republican voters oppose many of said preferences.

Upon taking unified control of the federal government last year, mainstream Republicans made passing trillion-dollar cuts to federal health-care spending — and massive reductions in the tax burdens of the wealthy and corporations — their top two legislative priorities. The Trump administration, meanwhile, pursued a deregulatory agenda that involved, among other things, expanding the liberty of coal companies to dump mining waste in streams, preserving the rights of retirement advisers to gamble with their clients’ money, and reducing federal oversight of predatory lenders.

These policies certainly demonstrated that elections have consequences. And yet, progressives who decried them were not lamenting the “the ordinary give-and-take of democratic politics,” so much as the ordinary “take-and-take-and-take of plutocracy.” There is a reason that Republican voters did not spend the 2016 campaign chanting, “drain the Medicaid expansion funds into the wealthy’s bank accounts,” or “make payday lenders immune from federal oversight again” — most Republicans do not want their government to do such things. In fact, polls show that a majority of the GOP electorate opposes cutting federal health-care spending, Medicaid funding, or the tax rates of the wealthy and corporations — and supports environmental protections of air and water, and strong federal regulation of Wall Street.

But one doesn’t have to trust such polls to know that there is no popular mandate for the agenda that Republicans have been implementing; one need only observe the party’s compulsion to lie about what that agenda is.

Donald Trump campaigned for the presidency on promises to replace Obamacare with a health-care plan that would “take care of everybody,” and to oppose any and all cuts to Medicaid. In making the case for repealing and replacing Obamacare in January 2017, Mitch McConnell suggested that Republicans’ problem with the program was that it had done too little to deliver universal access to affordable health care. “There are 25 million Americans who aren’t covered now,” the Senate majority leader told Meet the Press. “And many Americans who actually did get insurance when they did not have it before have really bad insurance that they have to pay for, and the deductibles are so high that it’s really not worth much to them.”

This “normal” Republican proceeded to co-author a health-care bill that would have cut Medicaid by nearly $800 billion; swollen the ranks of the uninsured by more than 20 million, and increased out-of-pocket healthcare expenses for much of the Republican base. McConnell attempted to shield this legislation from public scrutiny until shortly before holding a vote, while refusing to allow any extended hearings or public debate on its contents. In this fashion, the GOP came within a few of Senate votes of restructuring the American health-care system in a manner that it knew its own constituents did not support.

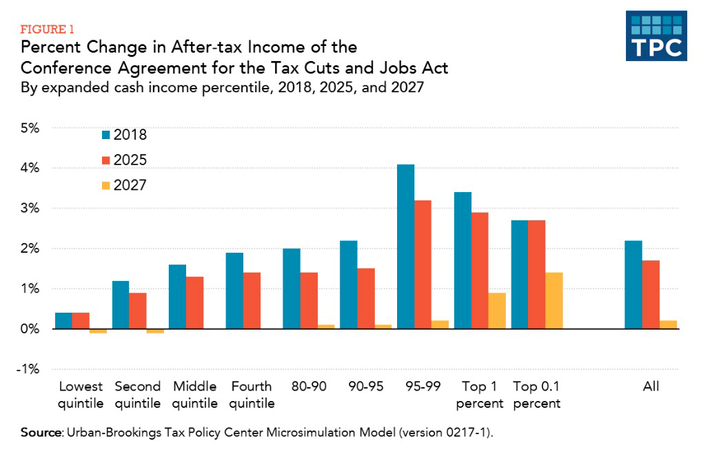

The party deployed the same tactics (more successfully) in its pursuit of regressive tax cuts. “Tax reform will protect low-income and middle-income households, not the wealthy and well-connected,” President Trump assured supporters in a speech in Indiana last September. “They can call me all they want. It’s not going to help. I’m doing the right thing, and it’s not good for me. Believe me.” National Economic Council director Gary Cohn went further, promising, “The wealthy are not getting a tax cut under our plan.” Three months later, the White House celebrated the passage of a tax cut package that delivered the lion’s share of its benefits to the top one percent.

This was not abnormal. Mainstream Republicans take a similar approach to governance at the state-level, where their party’s maniacal commitment to ever-lower taxes has left many deep red-states incapable of adequately funding the most basic government services — not least, public education. This is not because rank-and-file GOP voters would rather maximize the profit margins of Republican-aligned industries than keep their schools open five days a week. In Oklahoma, polls have longed suggested that a majority of voters support raising taxes on gas companies to increase teacher pay. The Republican legislature’s refusal to do so helped produce the teachers strike that rocked Oklahoma this past spring, while nearly identical developments played out in Arizona, Kentucky, and West Virginia.

It is certainly true that Democratic office holders also break campaign promises, and try to divert public attention from the more unpopular aspects of their agenda. But the party does generally run on the policies it intends to make its governing priorities — and is at least directionally honest about what those policies are. (Barack Obama did not campaign on a promise to slash Medicaid spending, or lower taxes on the super-rich.)

By contrast, the GOP’s commitment to a fiscal and regulatory agenda with no significant constituency — outside of its high-dollar donor class — leads the party to campaign on a combination of grossly mendacious descriptions of its true aims, or tribal appeals that have little-to-no policy content, like calls to imprison Hillary Clinton for ill-defined crimes, or repeal “sanctuary city laws” that do not exist, or force African-American football players to stand for the national anthem. (To the extent that “identity politics” are poisoning American civic life, the Republican Party’s commitment to a plutocratic agenda that it cannot afford to debate on the merits is largely responsible.)

In its mission to undermine popular government — so as to insulate the policy preferences of reactionary elites from majoritarian opinion — elected Republicans have received the indispensable aid of normal conservative jurists like Brett Kavanaugh. Over the past decade, the Roberts court has worked to systematically increase the influence that concentrated wealth can exert over American politics, while vetoing democratically enacted attempts to either constrain that influence, or else to buck the substantive preferences of the Republican donor class. The court’s efforts on this front include abolishing virtually all restrictions on corporate spending in American elections; overturning an Arizona law that attempted to counter such spending by providing candidates with public funds; legalizing most forms of political bribery; and gutting anti-trust law. The court has also come within one vote of striking down Barack Obama’s landmark health-care law on audaciously specious grounds.

Brett Kavanaugh’s legal writings suggest that he endorses the expansive conception of corporate rights established by the high court’s previous conservative majority. And he has also evinced sympathy for a theory of the executive branch which, in practice, all-but prohibits effective regulation of private industry.

In sum: The modern Republican Party has demonstrated a commitment to suppressing voter participation; reducing the influence of majorities over electoral outcomes; and subordinating the policy preferences of its own constituents to those of reactionary elites. It has further demonstrated a willingness to achieve the latter end by lying to its own base about its intentions for public policy; obfuscating the policy-making process to limit public awareness of the government’s activities; appointing activist judges who will veto democratically enacted legislation on dubious grounds; and stoking the most incendiary cultural divisions in American life.

To call such a party a “civic menace” is not say that democracy has become “a luxury that the country can no longer afford” — it is to say the very opposite.