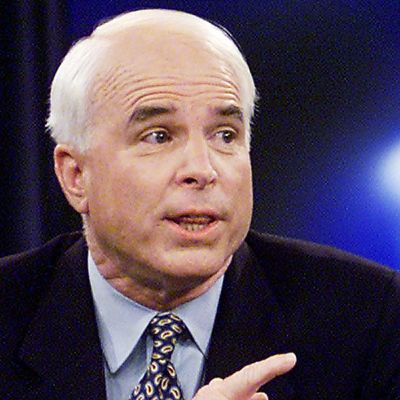

In February 2000, the fate and identity of the Republican Party seemed to come down to a primary contest between John McCain and George W. Bush. McCain had shocked Bush by recording a resounding victory in New Hampshire, deflating Bush’s healthy lead in the next primary to virtually nothing. If McCain won South Carolina, the entire Bush enterprise, built upon the expectation of inevitability, might have come crashing down. So, too, might have the grip held by the reactionary social and economic vanguard of the conservative movement.

It was a moment in time drenched in the familiar hyperbole of breathless horse-race journalism. But unlike most such moments, the importance of the contest has only grown over time. Today, from the standpoint of the Trump era, all the forces that were brought to bear against McCain in South Carolina are ascendant. And the historical importance of McCain’s doomed rebellion looms larger than ever.

McCain’s quest for the nomination began as a gadfly candidacy organized around his wartime heroism and idiosyncratic support for campaign finance reform. As the Establishment coalesced around Bush, McCain wandered into what, quite by accident, developed into a full-blown ideological insurgency. McCain denounced Bush’s “tax cuts for the rich” and the widening income inequality they would exacerbate. He depicted his candidacy as the ideological heir to Teddy Roosevelt, a progressive who had attacked the political influence of the wealthy.

McCain’s populist formulation struck a chord with the party base, which had little innate interest in reducing the tax burden on the rich. But the Republican elite viewed McCain with perfect horror. His attempt to reimagine the party in populist terms, rather than as a vehicle for the upward redistribution of wealth, posed an existential threat. The fight they waged in South Carolina reflected their understanding of the danger of his apostasy.

The National Rifle Association, the religious right, the business lobbyists centered around taxophobic party activist Grover Norquist, along with conservative media, descended upon the state. McCain’s extraordinary heroism in war, combined with Bush having pulled strings to get a safe post in the Texas National Guard, gave the insurgent a natural connection to the state’s outsize veteran population. But Bush’s campaign reframed the question by depicting McCain as a cultural alien, and Bush as one of them.

Bush delivered a speech at Bob Jones University, a white Evangelical outpost that still banned interracial dating. The attacks on McCain were wild. Flyers accused him of having a black child (McCain had adopted a daughter from Bangladesh). Various attacks charged McCain with having turned against his country in captivity. The war hero became a coward, and the laggard president’s son a hardscrabble good ol’ boy.

After South Carolina, McCain’s crusade to revive Roosevelt Republicanism drove him farther and farther away from his party. Over the next few years, he carved out a completely unique ideological identity within his party, co-sponsoring a Patients’ Bill of Rights, a bill requiring background checks at gun shows, regulations requiring higher auto-emission standards. He wrote an article in the liberal Washington Monthly calling for expanded national service. He very nearly left the Republican Party.

But McCain also came to believe that he had no presidential future outside the Republican Party, and that his Rooseveltian vision had no future within it. In 2004, McCain decided to reconcile himself to the party leadership. He stopped breaking from the administration and returned to the Republican orthodoxy that had defined him before his 2000 campaign. A small version of his heterodoxy returned when he cast a decisive vote against Donald Trump’s plan to repeal Obamacare. But by that point, he stood mostly alone, displaying the courage of a man who had no more political future to lose.

What McCain attempted in 2000 was something large and historic. He was trying to make the GOP into something like a regular right-of-center party similar to the kind found in other democracies — a party that did not reject academia and expertise, and was not bound by mindless anti-government dogmas like supply-side economics and climate science denial.

The coalition that crushed his rebellion in South Carolina has prevailed ever since. Donald Trump ramped up the cultural revanchism, and downplayed the economic orthodoxy, but the basic Republican formula has remained in place. And since South Carolina, nobody has even tried tried to replicate the feat McCain attempted. The Republican Party has been moving farther and farther right for four decades, and in one brief moment of rebellion, John McCain nearly reversed the course of history.