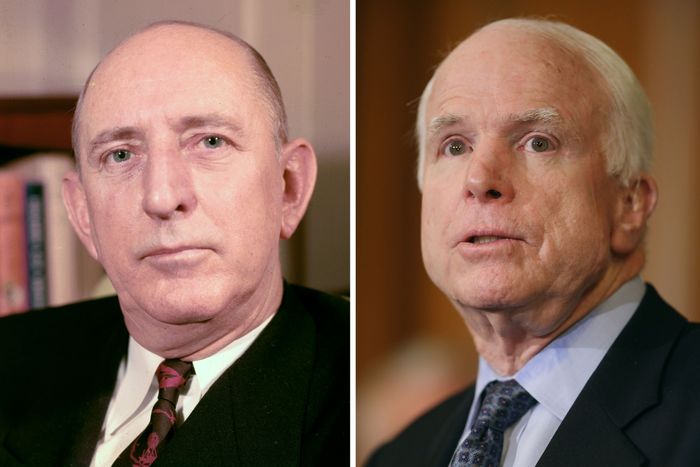

For 36 years, the three structures where the offices of U.S. senators (and their committees) are located have been named the Russell, Dirksen, and Hart buildings. There is now a bipartisan move afoot to rename the oldest building, the Russell Building, after the late John McCain.

From 1909 until 1958, the Russell Building was simply named the Senate Office Building (or, as some might think is appropriate, the SOB). When a second Senate building was opened in 1958, they became the Old and New SOBs. And finally, when a third building was being planned in the early 1970s, the Senate decided to name two of them after recently deceased senior figures, Democrat Richard B. Russell and Republican Everett M. Dirksen. The third building went through all sort of delays, not opening until 1982, but in 1976 it was named after Michigan Democrat Phil Hart, a much-liked figure who was dying of cancer.

So the current naming of these edifices was not the product of some highly deliberative process of adjudging contributions to the Senate or the nation, but rather a reaction to contemporaneous deaths (or in Hart’s case, a certain future death).

Still, the fact that the Russell Building is being targeted for redesignation isn’t attributable simply to the fact that McCain’s office (and for that matter, the Armed Services Committee that both he and Russell chaired) was located there. Russell’s long career (he served in the Senate from 1933 until his death in 1971) was multi-faceted. He was a staunch New Dealer who famously won his first full term by beating hyperreactionary Eugene Talmadge, and sponsored the first national free school lunch program. He was also one of the principal architects of U.S. defense strategy after World War II. A wizard in the use of Senate procedures and traditions, Russell was one of Lyndon B. Johnson’s chief mentors. An entire volume of Robert Caro’s epic biography of LBJ, Master of the Senate, revolves around Russell’s willingness in 1957 to allow a desiccated civil-rights bill to emerge from the Senate out of a desire to help Johnson become president.

But that was the exception that proved the rule. The 1957 bill was the opening wedge in a drive that LBJ built on as president to enact the sweeping 1964 Civil Rights Act over a determined opposition led by Richard B. Russell. And it is as the last great leader of southern segregationists that Russell will always be renowned.

Although Russell generally avoided the crude, blatant racism of many of his southern colleagues (including his long-time junior Senate colleague, Eugene Talmadge’s son Herman, who did eventually clean up his own act as well), it was precisely the respect in which he was held in the Senate that made him such a formidable champion of Jim Crow in its dying days. And there was no question where he stood on racial equality, as Walter Shapiro pointed out last year:

As historian Gilbert C. Fite wrote at the conclusion of his biography of Russell, “White supremacy and racial segregation were to him cardinal principles for good and workable human relationships. [Russell] had a deep emotional commitment to preserving the kind of South in which his ancestors had lived. No sacrifice was too great for him to make if it would prevent the extension of full equality to blacks.”

Perhaps in renaming Russell’s building after John McCain the Senate would be engaging in the same sort of sentimental tunnel-vision that led them to so honor the genteel racist from Georgia and the mellowed old reactionary Everett Dirksen in 1972. But it’s time Richard B. Russell’s name came down from the Old SOB. His era is long past, thank God.