Shortly after Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony to the Senate concluded Thursday, Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn told reporters that he “found no reason to find her not credible.” Few, if any, of Cornyn’s colleagues and allies in the media did, either.

Thus, when Brett Kavanaugh came before the the upper chamber Thursday afternoon, Senate Republicans had no means of discrediting the account that had preceded his. Nor did they have much interest, as a political matter, in publicly disparaging an ostensibly credible sexual assault survivor. So, instead, they centered their defense of Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee on the claim that Ford’s allegations were perilously lacking in corroborating evidence.

“You are not guilty because somebody makes an accusation against you in this country,” Cornyn informed Kavanaugh Thursday afternoon. “We are not a police state. We don’t give the government that kind of power. We insist that those charges be proven by competent evidence.”

Variations on this argument were recited (with varying levels of righteous indignation) by nearly every Republican on the committee, as well as Kavanaugh himself. But there was one conspicuous problem with this line of reasoning: If Ford’s claims were credible, but lacking in substantiation, why shouldn’t Kavanaugh’s nomination be put on hold while the FBI further investigated her allegations, as well as those of Deborah Ramirez and Julie Swetnick?

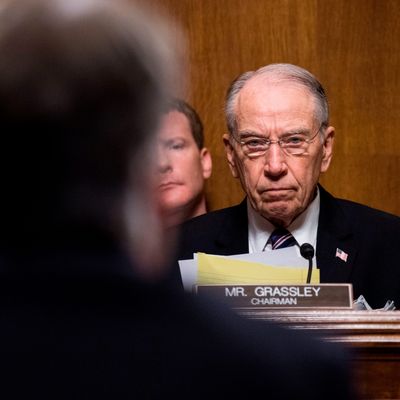

Variations on that question were recited (with varying levels of righteous indignation) by nearly every Democrat on the committee. And each time, the Republicans would respond with what amounted to a non sequitur: “The FBI does not, in this or any other case, reach a conclusion,” Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley asserted (quoting a statement Joe Biden made during Clarence Thomas’s hearings) multiple times. “They do not reach conclusions. They do not make recommendations.”

It is true that the FBI would not offer a recommendation for whether the Senate should consider Brett Kavanaugh guilty of sexual assault. But it’s also true that no one is asking the FBI to do that: The request is merely that federal law enforcement gather further evidence, so that the Senate might have the opportunity to better assess the veracity of an allegation that Cornyn, himself, has deemed to be credible. Which is to say: Senate Republicans spent the afternoon lamenting the lack of evidence at their disposal — and then indignantly rejecting offers to supply them with further evidence.

To the extent that Grassley and his colleagues addressed this dissonance, they did so by insisting that there were no further facts left to find: The allegations made by Julie Swetnick and Deborah Ramirez were patently untrue, while the one made by Christine Ford had already been comprehensively investigated.

But both of those claims are plainly false. The most obvious problem with the latter assertion was the absence of Mark Judge from Capitol Hill Thursday. Ford testified that Judge was an eyewitness to the assault in question. Judge has written extensively about his history of problem drinking, and also, allegedly, once told an ex-girlfriend that he and another man had taken turns having sex with a drunk girl. But instead of subpoenaing Judge — and subjecting him to interrogation in the Senate chamber — Senate Republicans declared themselves satisfied with a single-paragraph statement saying that his friend Brett Kavanaugh would not be capable of the behavior Ford describes.

Kavanaugh and the Republicans treated Judge’s willingness to issue a sworn declaration — which would put him at risk of perjury if his claim was proven false — as a testament to his credibility so strong that no further interrogation was required.

And yet, Julie Swetnick also submitted a sworn declaration to the committee, in which she claimed, at the risk of perjury, that Kavanaugh and Judge had participated in gang rapes of drunk girls at parties in the early 1980s. In Swetnick’s case, however, the existence of a sworn declaration was deemed not only insufficient to establish her credibility, but failed to even render her account worthy of any consideration, whatsoever.

Meanwhile, Kavanaugh (unlike Ford) offered the committee plenty of cause for questioning his credibility. The federal judge stated over and over again that “all four witnesses [cited by Ford] said that it did not happen” (“it” being his alleged assault of Ford). But that claim was demonstrably untrue. Ford claims that she was assaulted in a private bedroom in the presence of Kavanaugh and Judge and no one else. She further claims that she left the house after the assault and never told any of the party’s other guests about it. Leland Keyser, a friend of Ford’s who Ford claims was at the party, has not said that the alleged assault never happened, but merely that she does not remember the party — which would have ostensibly been, for her, an unremarkable evening of drinking that occurred 36 years ago. Even Mark Judge, in his initial statement, did not deny Ford’s claim but merely said that he did not recall the events she described.

Now, perhaps a layman could be forgiven for failing to appreciate the distinction between “the witness says the crime didn’t happen” and “the witness says she doesn’t remember the party where the crime is alleged to have happened.” But, generally speaking, one expects a Supreme Court justice to use words precisely — particularly, words that are meant to characterize testimony about a serious crime.

And, as Jonathan Chait notes, this was hardly the only apparently mendacious statement Kavanaugh made in the course of his confirmation process:

Kavanaugh has said too many things that strain credulity for all them to be plausibly true. He almost certainly lied about having had access to files stolen by Senate Republicans back when he was handling judicial nominations in the Bush administration. His explanation that the “Renate Alumni” was not a sexual reference is difficult to square with a fellow Renate Alumnus’s poem ( “You need a date / and it’s getting late / so don’t hesitate / to call Renate”) portraying her as a cheap date. His insistence that “boof” and “devil’s triangle” from his yearbook were references to flatulence and a drinking game drew incredulous responses from people his age who have heard these terms. His claim that the “Beach Week Ralph Club” was a reference to a weak stomach seems highly unlikely.

So, at the end of the day, we’re left with one witness whose testimony sounded credible, even to Cornyn; and another who appears to have made a series of facially untrue statements. We have one side that has requested the gathering of further evidence to adjudicate the dispute, and one side that vehemently opposes such fact-finding.

Make of that what you will.