Last weekend, Americans weathered a “once in a lifetime” storm for the fourth time in 13 months. After a summer of unprecedented wildfires in the West, hurricane season has (once again) brought “unprecedented” devastation to communities on the East Coast. Faced with such ecological upheaval, our primeval ancestors would be scrambling to discern what they’d done to provoke nature’s wrath.

We modern humans are a bit less confused, but much more complacent. We don’t need to ask a shaman why monsters like Florence are paying us such frequent visits. We don’t need burn a witch to find out what’s bringing heat waves to the Arctic. Everyone who (earnestly) wishes to know why this is happening knows the three-word answer: manmade climate change.

And we know what we have to do to fix it. We don’t lack the technological capability and industrial capacity to build a sustainable economy. If America’s finest minds could figure out how to split the atom in the 1940s — and put men on the moon by the end of ’60s — they can work out how to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by the middle of this century.

If technical expertise isn’t a barrier to radical action on climate, money certainly isn’t an issue. If our aim is to maximize Charles Koch’s prosperity during his last few years on Earth, then there might a tension between reducing carbon emissions and achieving our economic goals. But if we wish to maximize human prosperity during our children’s lifetimes, no such trade-off exists. The costs of inaction on climate change are exorbitant; the return on investment in sustainability, massive. Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley estimate that every degree of Celsius warming will cost the global economy, on average, 1.2 percent of GDP. On the other hand, a recent report from the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate found that a global shift to sustainable development would net humanity an extra $26 trillion by 2030.

On its face, the choice confronting humanity shouldn’t be a difficult one: We can either mobilize against climate change as we once did for world wars, and, thereby, safeguard the long-term survival of human life on planet Earth while making our civilization immensely wealthier — or, we can sit back and watch cable news coverage of this month’s “1,000-year storm” until our coastal cities sink into the sea.

Alas, by all appearances, we Americans are opting for door No. 2. And if the world’s most powerful nation (and prolific per-capita carbon emitter) fails to take radical action on climate, the prospects of other countries doing so will be slim.

Last week, Vox’s climate columnist David Roberts offered a succinct explanation for our baffling decision: While we have the technology, policy tools, and economic incentives necessary for radical action, we lack “the political will.”

This assessment is almost certainly correct — but it also has the potential to mislead. In a (self-proclaimed) democracy like the United States, “political will” and “popular will” are often treated as synonymous. And in American political discourse, the idea of massively expanding the public sector to combat environmental threats is often treated as the eccentric fantasy of a far-left fringe. Thus, some might read “America lacks the political will to pursue an ambitious climate agenda” as “the American electorate does not support an ambitious climate agenda.” And that would be unfortunate — because the latter claim is just one of our reactionary elite’s many convenient untruths.

New research from Data for Progress (DFP) throws this point into sharp relief. To assess the political viability of a “Green New Deal” — which is to say, a program of massive public investment and government hiring aimed at reducing America’s carbon emissions as rapidly as possible — the progressive think tank conducted an analysis of existing public-opinion data, while commissioning a battery of original polls. In doing so, they found majoritarian support for a wide range of ambitious environmental policies, including a federal “green jobs” guarantee.

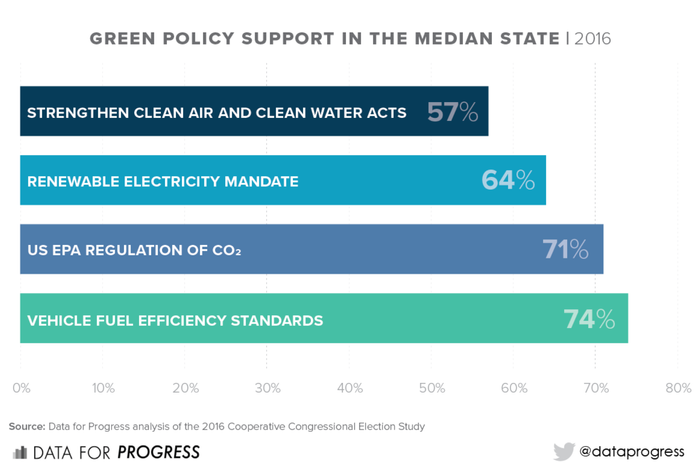

Examining survey data from the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, DFP found overwhelming public support for “strengthening enforcement of the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, raising fuel efficiency standards, setting a renewable electricity mandate, and allowing the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate carbon dioxide.”

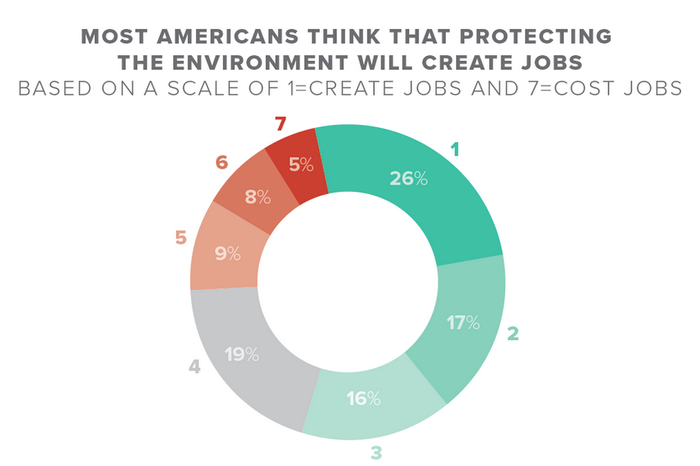

Meanwhile, a glance at the American National Election Studies (ANES) 2016 findings revealed that some 58 percent of Americans believe that efforts to protect the environment create more jobs than they kill.

Most remarkable, however, were the results of DFP’s original polling, which it conducted in partnership with YouGov Blue. When asked whether they would “support or oppose giving every American who wants one a job scaling up renewable energy, weatherizing homes and office buildings, developing mass transit projects, and maintaining green community spaces,” 55 percent of respondents said yes, while just 18 percent said no — making a “green jobs” guarantee slightly more popular than a generic version of the proposal (i.e., a jobs guarantee without an environmental angle). What’s more, 51 percent of voters said they’d be more likely to vote for a candidate who supported a green jobs guarantee, while just 20 percent said they’d be less likely to do so. Meanwhile, the idea of massively expanding “big government” — for the sake of subsidizing big coal’s competitors — was only a single percentage point underwater with voters who backed Donald Trump in 2016.

Of course, policies that play well in opinion surveys don’t necessarily bring voters to the polls. It is absolutely true that, as of this writing, there aren’t a whole lot of single-issue climate voters in the United States. Most Americans are more concerned with their everyday material challenges — and/or, sources of cultural alienation — than with the long-term trajectory of global temperatures. When Gallup asked Americans to name their country’s most important problem last month, just 2 percent chose “environment/pollution”; 16 percent cited “immigration/illegal aliens.” This doesn’t mean that the American people, as a whole, want the government to prioritize immigration restriction over environmental protection. As DFP’s findings would suggest, the opposite is true: Earlier this year Gallup found that 62 percent of voters believe that the government is doing too little to protect the environment — while 57 percent want policymakers to prioritize environmental preservation over economic growth. By contrast, just 29 percent of the public told the pollster that immigration to the U.S. should be reduced.

Thus, the fact that immigration restriction looms so much larger in our politics than environmental protection is not a reflection of the popular will. There are more Americans who want to reduce carbon pollution than ones who wish to cut immigration — the latter are just much more committed to, focused on, and organized around their cause.

Our problem, then, isn’t that voters won’t let their political leaders take radical action on the most important issue facing humanity, but that voters aren’t forcing their leaders to prioritize the long-term survival of civilization over the myopic concerns of entrenched interests.

Or else, if we stipulate that some of our (Democratic) political leaders earnestly want to bring about a radical policy response to climate change, then the problem is that such leaders haven’t found a way to turn passive public support for such an agenda into a mobilized political movement. Which is understandable. How to pull off that task is a genuinely difficult question.

But there’s reason to think that a “Green New Deal” might be part of the answer. In its report, Data for Progress frames that policy as a means of not only achieving climate sustainability, but also, of providing living-wage jobs to underpaid workers; forcing private-sector employers to raise wages and improve benefits; and redressing racial injustice by reducing disparities in access to clean air, clean drinking water, and green recreational space.

Climate might not (yet) be highly salient to the average Democratic voter; but jobs and racial justice are. DFP’s polling suggests that Democratic politicians could rally voters around ambitious “intersectional” climate policies — if they can find the personal will.