Courtesy of Sony Pictures

Good news: The assembly of Michael Jackson rehearsal footage bearing the apt title This Is It does not play like the work of necrophiliac greedheads squeezing the last dollar out of a moonwalking skeleton. It’s vivid, illuminating, and sometimes — more often than you’d think possible — inspiring. Despite the (anonymous) reports in the days after Jackson’s death of his inability to rise to the occasion, the prospective London concert series that consumed his final months doesn’t look to have been an inherently doomed enterprise. Touch and go, certainly. But Jackson’s discipline and drive outlasted his body. He wanted one last time to go onstage and be as he was.

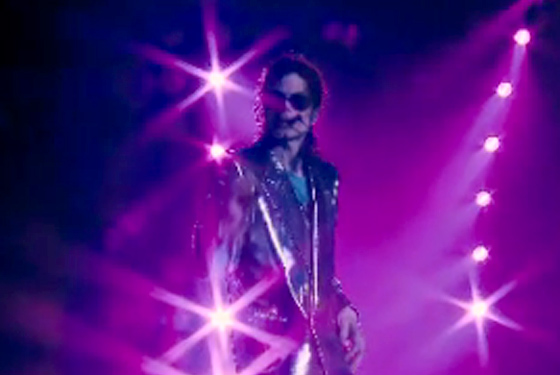

He doesn’t spell that out, and neither does anyone else. This Is It provides no context, no posthumous commentary on the sad trajectory of Jackson’s life, no reference to anything outside the Los Angeles auditorium in the final weeks of rehearsal before the huge company would depart for Great Britain. This footage would probably have ended up as a DVD supplement to a concert film. There are a Chorus Line–like casting session and brief interviews with overawed dancers, singers, and musicians (“Michael is the epitome of one of the great entertainers of all time”), but most of the movie is process. The concert series — his first time onstage in over a decade — was to feature his big hits, from “ABC” with the Jackson Five through “Billie Jean,” “Black and White,” all the way up to that eco-anthem with the elephants and rain forest. There would be elaborate multimedia interpolations, among them updates of the incomparable “Thriller” and “Smooth Criminal” videos. There would be fireballs, elevators, and a bulldozer. Jackson did nothing small. There would be no acoustic set. There would be no acknowledgment that he was a 50-year-old man.

The challenge for the film’s director, Kenny Ortega (who was also directing the stage show), and the army of heirs, moneymen, and meddlers, was to walk a delicate line: They had to remind us why Jackson was the King of Pop but also to leave in signs of his vulnerability. Too much potency and our morbid curiosity would go unsatisfied; too much pathos and the charge of exploitation would be even harder to fight.

They got the balance about right. Jackson’s legs are pool-cue thin, so that every time he lands you fear a crack … Yet when Ortega splits the screen into run-throughs on two or even three different days, the dancing is awesomely on point. Jackson’s not just keeping up with the superhuman young specimens in his troupe; he’s credibly leading them. “Smooth Criminal” has the old rat-tat-tat electricity. “Beat It” has you bouncing in your seat even if Michael is a quarter century older than the members of the gangs he’s magically separating. He’s not impersonating Michael Jackson, he is Michael Jackson — and everything emanates from him. Before the final round of auditions, Ortega tells the prospects, “Dancers in a Michael Jackson show are an extension of Michael Jackson” — and as skinny as Jackson is, they do seem like projections of his spirit and will. Another choreographer explains that it’s not just athleticism that’s required: “If you don’t have that goo, that ooze coming out of you, you’re not gonna get the job” — which sounds alarming, but makes perfect sense. The choreography is all snap and ooze, snap and ooze, violent spasm and simmer.

… and all of it controlled by the man himself. “That can’t trigger on its own,” he says, more than once, about the back-up dancers’ moves or a light change or a downbeat. “I gotta cue that.” Jackson emerges here as a control freak who swaddles his commands in diapers of love: “It’s not right but that’s okay, it’s all for love — just get it there.” Having once been terrorized in rehearsal by his dictatorial dad, he’s bent on getting the same results in a different way. “I know you mean well,” he tells his sound crew, pointing to his headphones after a botched performance of “ABC.” “I’m trying to adjust the inner ears with … the love, the love, L-O-V-E.” No one knows what he’s babbling about, but at least he’s not humiliating anyone. From offscreen, Ortega speaks to him as he might to the 6-year-old monarch in The Last Emperor.

The voice — well, that was a potential disaster. Accounting for his pitiful sounds from the stage in “I Can’t Stop Loving You” (“I’m trying to conserve my throat, please, so understand … I shouldn’t be singing right now. I’m warming up to the moment. Don’t make me sing out. [To singer Judith Hill] You’re fine to do it. I gotta save my voice … ”), he seems to think the problem is his cords; to my inexpert ears, it sounds like he doesn’t have the lungs. In some numbers, his vocals have clearly been sweetened, but Ortega leaves in enough wobbly notes to let you know that even the oohs and yips were an effort. (So many top singers lip-synch these days that they could probably have done a work-around — but the proud, perfectionist Jackson might not have been able to live with that.)

One of the techies gushes that Jackson always has to “push the boundaries” — which must have been especially worrisome to someone whose boundaries had already been pushed as far as any human’s can go. Perhaps if he had pulled this concert series off, he might have been able to leave that young Michael behind and move in a new direction … reinvent himself … maybe alongside John Lennon if Mark David Chapman had misfired … and Buddy Holly on back-up guitar if his plane hadn’t crashed, and … Oh, what’s the use? He was a mess and destined to self-destruct. When he held forth onscreen in a prologue to that song about the danger to the Earth (“I love the planet … I love trees … What have we done to the world?”), all I could think was, “What have you done to your own natural state?” In the name of evolution, this beautiful African-American boy turned himself into a whey-faced ghoul with a nose whittled down to cartilage. Maybe in the end he displaced his horror at his own self-mutilation onto Mother Nature.

At the premiere last night, I was worried when Ortega introduced the film to audiences in seventeen cities via a live feed from L.A.: “Tonight we come together in the name of blah blah … this is for the fans blah blah … the last sacred documentary of our leader and friend blah blah … ” Would Michael Jackson be thrust at us as a deity? Maybe if the footage had supported it. A new video made for “Smooth Criminal” onstage showed the 50-year-old Jackson interacting with Rita Hayworth as Gilda and dodging Bogie’s bullets — and it seemed wrong, a horrible disconnect. That Jackson doesn’t belong with Hayworth and Bogie, but the earlier Jackson of the original videos of "Billie Jean" and "Beat It" and "Black and White" and "Smooth Criminal" sure does. The Jackson of This Is It is worth treasuring for a different reason. Like all great artists behind their mythical facades, he was in there working, counting steps, working, trying to hit the notes, working, and working, and still, always, working …