The election of Donald Trump stirred slumbering spirits of resistance in the LGBTQ community. More acutely, it stirred them in factions of the gay and lesbian communities that had perhaps become comfortable under the Obama administration. Pride parades became marches, which drew on a rich history of LGBTQ protest. But on the anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall Riots, it seems fitting to ask: Are we truly returning to our radical roots?

Earlier this month, No Justice No Pride, an activist group challenging corporate sponsorship in pride parades, disrupted D.C.’s Capital Pride event over its relationship with Northrop Grumman, a weapons manufacturer, and Wells Fargo, which helped financed the hotly contested Dakota Access Pipeline. Activists also called for Capital Pride to prevent the LGBTQ liaison unit of the Metropolitan Police Department and military personnel from officially participating, citing police brutality across the U.S.

The very next day was the D.C. Equality March for Unity and Pride, which was inspired by the Women’s March on Washington that flooded the streets of the nation’s capital in January. Both the disruption and the march were ostensibly acts of resistance, but they submitted two very different models of achieving justice, despite the fact that both genuflected to Stonewall’s influence.

It’s indicative of a deep divide between activists across the country: those who joined the #Resistance after Trump’s inauguration, and social justice advocates who had also taken to the streets under Obama. It’s not that cleanly delineated, of course. People who attended the Women’s March could very well have been involved in Black Lives Matter before the election. So perhaps the divide is more aptly described as those who seek incremental reform within our current sociopolitical system, and those who seek reform by dismantling that system altogether.

In the context of the LGBTQ community, that meant higher scrutiny than ever on corporate relationships with pride events this year. What emerged could understandably be seen as a paradox: pride organizers were more interested in activism than usual, and activists had more problems with pride organizers than ever.

But it makes sense when we consider that, in the end, the bulk of the LGBTQ people in what could be called the anti-Trump #Resistance does want something different from the LGBTQ people who would align themselves closer to No Justice No Pride. It also makes sense that the former would have less of a problem with corporate relationships and police presence than the latter, considering the former’s willingness to work within the present system to achieve change.

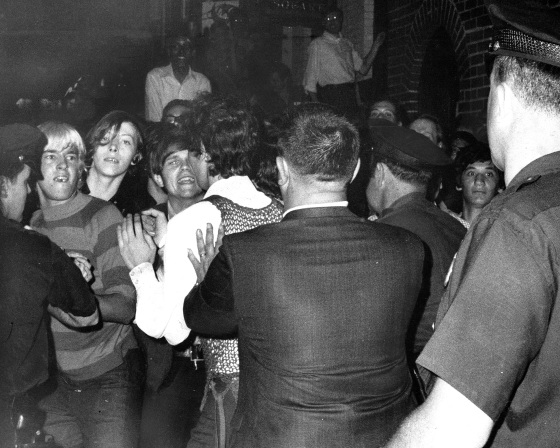

Which approach to justice is the best method is subjective and up for debate. But what’s undeniable is that the stauncher adherents to both sects see themselves, and Stonewall, in very different lights. To some, it exists in the immediate present as a reaction to targeted police brutality. To others, it exists as a kind of predecessor, closer in form to its present status as a hallowed monument, and today’s LGBTQ activism is derived from it as opposed to embodying it.

One thing we know for sure: There were no corporate sponsors of Stonewall, and this is true of many present-day movements. Whether you believe corporate sponsors are indicative of a movement’s evolution or of its decay is likely indicative of what kind of activist you are.