Just before members of the Gay Officers Action League (GOAL) marched past the Stonewall Inn, the finish line of last year’s New York City Pride March, a small group of activists slipped past the barriers and chained their hands together to prevent the officers from passing, a protest technique called a “lockdown.”

Dozens of cops working security at the march surrounded the protesters, and, over shouts of “f--k the police” and “racist, sexist, anti-gay, NYPD, KKK,” began to break through what appeared to be chains and rubber tubes the protesters had used to lock themselves together. Twelve protesters affiliated with the group No Justice No Pride were arrested, and after a brief delay, the march continued.

The irony of the incident was not lost on many in the crowd — cops arresting gay people in front of the Stonewall Inn, the very place where homophobic police brutality sparked the modern LGBTQ rights movement nearly five decades years prior. In fact, New York City’s first gay pride march, which was held on June 28, 1970, was organized to commemorate the one-year anniversary of what has become known as the Stonewall Riots — when in 1969 patrons of the now-iconic gay bar finally had enough after yet another police raid.

“We have to come out into the open and stop being ashamed, or else people will go on treating us as freaks. This march,” activist Michael Brown told The New York Times on that day in 1970, “is an affirmation and declaration of our new pride.”

Last year’s clash between the NYPD and anti-police protesters was not an isolated incident. Protesters in several cities across the U.S. and Canada have, over the past two years, tried to prevent, disrupt or minimize the presence of police officers in pride marches — even though the officers impacted are typically members of LGBTQ police groups, like GOAL. Nonetheless, protesters say they’re doing so to take a stand against police brutality and harassment of marginalized groups, namely people of color and the transgender community.

EARLY DAYS OF GOAL

The relationship between the police and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer community has long been fraught, but for LGBTQ cops, the right to march in pride is a hard-fought civil rights victory.

In the decade after that first pride march on June 28, 1970, New York’s gay rights movement made so much progress that by 1981 the police force itself was facing LGBTQ activism from within. Gay cops in New York City, for example, led by Officer Charles Cochrane, sought to form their own employee resource group, like the ones that existed for Hispanic, Irish-American and African-American cops.

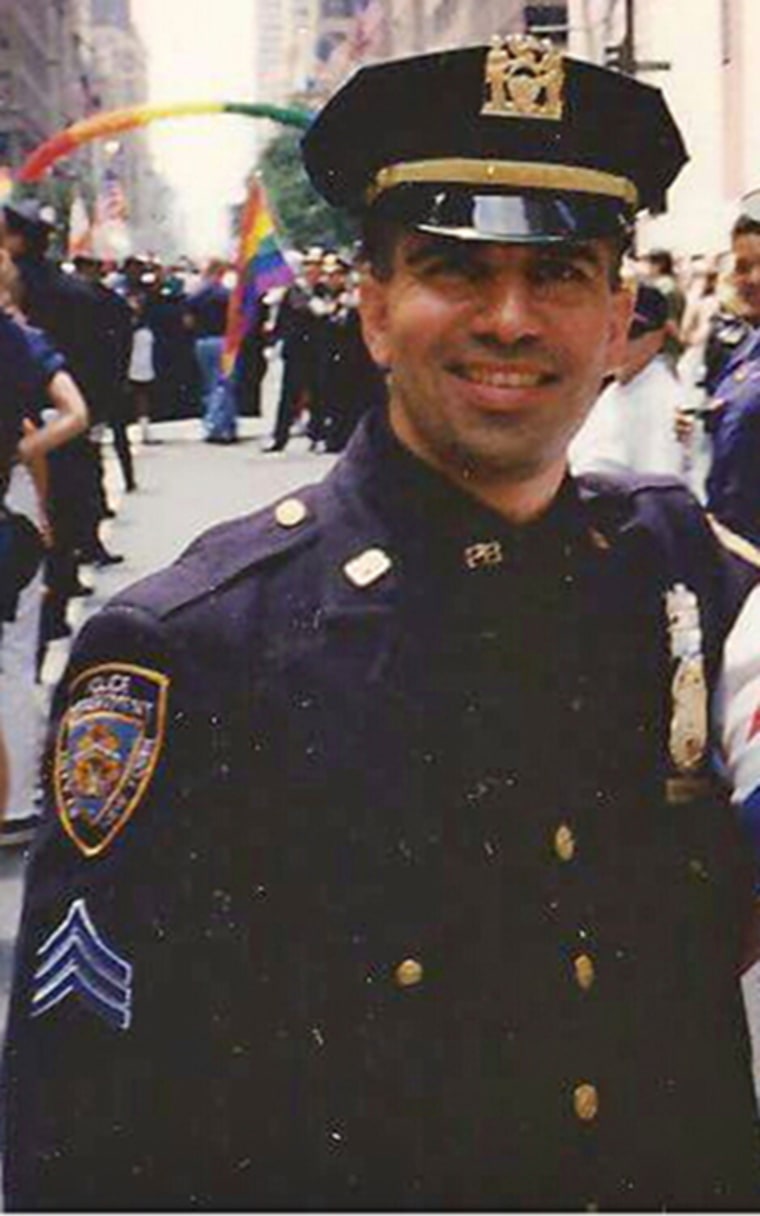

Edgar Rodriguez, now a retired NYPD sergeant, was still in the New York City Police Academy when Officer Cochrane entered his classroom in 1982.

“We all stood to attention, [the instructor] introduced him in full uniform, and said he had an announcement about a fraternal organization he was starting,” Rodriguez remembered.

Cochrane told the rookies his new group was called the Gay Officers Action League, or GOAL. A few months earlier, Cochrane had become the first NYPD officer to publicly come out when he announced that he was gay at a city council meeting in November 1981.

“Is anybody here interested in joining?” Cochrane asked the class.

“When he said this the room fell silent,” Rodriguez recalled, “and I could hear a faint snicker in the back of the room.”

Rodriguez also said he could hear his “heart thumping in [his] chest.”

“I was deeply closeted, and I thought, ‘This has got to be a setup to see who’s closeted and fire them,’” he recalled. “I never raised my hand.”

Later that day, a woman from Rodriguez’s Police Academy class asked him which room the gay officers’ group was meeting in. “Why do you ask?” Rodriguez responded. “Well, I’m a lesbian,” she replied. Rodriguez said he thought to himself, “What’s a lesbian?”

Rodriguez, who kept his sexuality to himself in his early days as a cop, recalled overhearing on several occasions racist, sexist and homophobic comments from his largely straight, white and male colleagues back then.

When he was posted to New York City’s 6th Precinct, which covers Greenwich Village, he recalled a senior officer asking him, “So you work with all the fags?” Rodriguez corrected him, responding, “You mean lesbians and gays?” Rodriguez said the officer apologized and told him their interaction had been a learning moment. “He kept nudging me in the arm and said, ‘You know kid, you really taught me something.’”

Trying to make change from within was a slow process for Rodriguez, who said homophobia was rampant in the NYPD in the ‘80s. He recalled a particularly daunting incident when a fellow officer who had been patrolling Macombs Dam Park, where the new Yankee Stadium now stands, encountered a well-known gay cruising area. Later that day in the locker room, Rodriguez overheard him say, “F-----g faggots. If I ever find out that one of us is the f-----g fggot, I’m going to blow his head off ‘by accident.’”

“I remember feeling the fear shoot through my body, and I thought, ‘I’m never going to come out,’” Rodriguez said.

But eventually, he did come out. Rodriguez recalled marching in his first NYC Pride March with GOAL in the late ‘80s. He was still closeted to most of his fellow officers, but when he was off duty, he lived openly in the gay neighborhoods of New York City.

“We didn’t have uniforms,” Rodriguez said of that first march. “I was terrified. I was closeted.” He said he put on a hat and sunglasses and held a banner in front of his face as he began to march.

As the march proceeded, however, Rodriguez said something changed.

“A crowd of spectators let out a roar of acceptance that just charged through my body, and it was one of the most incredible experiences I’ve ever had in my life,” he said. “The energy that came from that crowd of love and support — I threw off my glasses and my hat and marched proudly.”

Then in 1996, 14 years after Rodriguez declined to raise his hand when Officer Cochrane spoke in front of his Police Academy class, Rodriguez became the president of GOAL.

But even in the mid-’90s, Rodriguez said the NYPD had a long way to go in terms of LGBTQ acceptance. That’s why in 1996, the year he took the helm at GOAL, the group sued the NYPD for discrimination. As part of the suit, GOAL wanted to march in the annual NYC Pride March in uniform and with the official police marching band — a request that had been rejected in previous years. By June of that year, GOAL had won concessions from the NYPD and was permitted to march in uniform, to use the marching band and to host an event at NYPD headquarters. The lawsuit worked.

Rodriguez said even though GOAL had been participating in the NYC Pride March for years before the lawsuit, it was different afterwards.

“The roar from the community was 10 times louder than it was when I first marched outside of uniform,” Rodriguez said.

COPS VS. PROTESTERS

From Washington, D.C., to Sacramento, a number of progressive LGBTQ activists, some of them too young to remember the gay police activism of the ‘80s and ‘90s, view cops to be an unwelcome — and even threatening — presence at pride events.

In addition to getting cops out of pride, many of these different activist groups also have an array of social justice demands. Last year at Capital Pride in Washington, D.C., a group called No Justice No Pride (NJNP) blocked the pride parade and forced it to reroute. The group says it exists “to end the LGBT movement’s complicity with systems of oppression that further marginalize queer and trans individuals.”

Part of those systems of oppression are the police, according to Ale Jacinta, a member of No Justice No Pride. She said the point of the organization is to transform Capital Pride from a day when a majority of the community gets sloshed and watches a parade to a day of building community power.”

In 2017, No Justice No Pride delivered a list of demands to Capital Pride’s organizing committee. They demanded transgender people and members of local Native American tribes be named to paid positions on Capital Pride’s planning committee. The group also demanded that the event “stop celebrating the police,” prevent the Metropolitan Police Department from participating in the march and ban all law enforcement agencies from recruiting at the event.

“At the end of the day, NJNP doesn’t want a formal cop presence in the parade,” Jacinta said. “We look at our history and our present reality and see there is very little accountability for the extrajudicial murder of civilians, especially brown and black folks.”

But Capital Pride held fast, and a diverse group from the Metropolitan Police Department marched in both the 2017 and 2018 parades — guns holstered and in uniform. Unlike in 2017, No Justice No Pride did not block the 2018 Capital Pride march, held earlier this month. Jacinta said the group decided this year to focus on “taking back D.C.'s historically trans sex worker stroll” to protest harassment they and other trans activists say they face from the Metropolitan Police Department.

Other activist groups have had better success in preventing or minimizing the presence of police officers in pride events. In Sacramento, police did not march in this year’s pride event on June 10 due, in part, to the community outrage that followed the murder of Stephon Clark, an unarmed black man shot by two cops in March.

In Minneapolis, the city’s police chief told his officers if they want to march in the Twin Cities Pride event on Sunday, they would have to do so out of uniform and unarmed. Like Sacramento, community tensions have been simmering in Minneapolis following a high-profile police shooting.

Last year’s anti-police protest at the NYC Pride March was organized by a number of community groups operating under the No Justice No Pride umbrella. In a Facebook post following the protest, the New York group Hoods4Justice explained why it joined the protest effort.

“We stand against any police presence in Pride, since police have never stood with us. The police serve as the state’s puppets to terrorize Black, Brown, and working class communities. The notion that police serve all people is a myth,” the post stated. “Trans women who survive hate attacks are 6 times more likely to experience violence when dealing with police than cis-gender folks.”

Jay Walker, an organizer with the Reclaim Pride Coalition, a group involved with the No Justice No Pride movement, said the NYPD and Heritage of Pride, the LGBTQ group that organizes the annual NYC Pride March, have made a few concessions this year. The NYPD has agreed not to arrest pride participants for failing to wear required Pride March wristbands, and Heritage of Pride agreed to provide space in the march for LGBTQ activist groups, like ACT UP! New York and Gays Against Guns.

However, this year members of the Gay Officers Action League will march, as they have every year since 1996, in uniform with their guns holstered.

MOVING FORWARD

Rodriguez said while he knows where the protesters are coming from, he disagrees with their tactics.

“I understand the people of color and the other people who have been abused by officers that are representing the NYPD,” he said. “I know police brutality existed, I know it exists; I observed it when I was a rookie officer, and I saw it happen … but doing this is counterproductive.”

“They have to remember that it is us, the people of color, marching in uniform, and us, the LGBT people marching out in uniform. We are the people who were on the ground,” he added.

Rodriguez said when he was policing the 6th Precinct, which covers much of Manhattan’s gay neighborhoods, he once saw a transgender woman with blood streaming down her cheek running away from a group of men. He asked her if she was OK, and she just said, “I’m fine.”

“She was too afraid to let me help her, and the pricks who attacked her got away,” he recalled. “She was too afraid to embrace my willingness to protect her.”

NYPD Detective Brian Downey, the current president of the Gay Officers Action League, said imagery of uniformed LGBTQ cops marching proudly “is powerful,” and he hopes it will prevent people in the community, like the trans woman Rodriguez described, from being afraid of cops.

“I think that imagery needs to be displayed, because people to this day, I don’t know for what reason, people still don’t know we exist. People still don’t know we are a resource for people, and I think it is important that people know that,” he said.