Movie star and gay icon Judy Garland’s funeral was held June 27, 1969, in Manhattan’s wealthy Upper East Side neighborhood. Just hours after the “Wizard of Oz” luminary was laid to rest — shortly after midnight on Saturday, June 28 — the historic Stonewall uprising erupted just four miles south in the city’s bohemian West Village.

For decades, the two incidents have been tied together, treated more like cause and effect than coincidence.

“The combination of a full moon and Judy Garland’s funeral was too much for them,” Walter Troy Spencer wrote in the opening line of his Village Voice column on July 10, 1969. He then proceeded to call the Stonewall uprising the “Great Faggot Rebellion.”

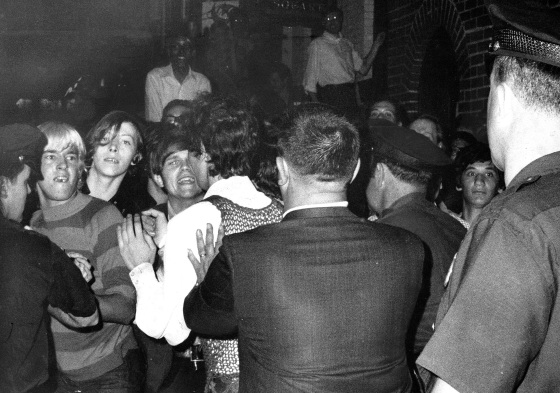

But witnesses to the now-iconic rebellion — including two of Spencer’s own colleagues at the Village Voice — have attributed what unfolded to LGBTQ people saying "enough is enough" when faced with yet another police raid on a gay establishment.

Stonewall witness and longtime gay activist Mark Segal calls the Garland claim “the biggest myth” surrounding the uprising.

“That really angers me and angers all of us who were here,” Segal told NBC News. “It’s an insult to each of us.”

“Some old songstress had nothing to do with it,” Segal said of Garland, who was 47 at the time of her death. “Our generation was wearing T-shirts and jeans. We were dancing to the Fifth Dimension and songs from ‘Hair.’ We were dancing to The Beatles, Motown. We weren't dancing or singing to Judy Garland.”

The Garland myth is just one of many surrounding the iconic Stonewall uprising. After all, back in 1969, not everyone was carrying a video camera in their pocket.

“Stonewall, like any major historical event that gets a lot of attention, has been interpreted in a lot of different ways,” George Chauncey, a Columbia University history professor and author of “Gay New York,” told NBC News. “There have been huge debates over who threw the first stone, who first fought back the cops.”

There’s even a debate as to who was actually there.

“This is what changed the world as far as the LGBT community is concerned,” Segal said. “Everybody wants their own little piece of it.”

But because there was no video of the multiday-uprising, barely any photographs and just 13 arrests from that first day, it’s almost impossible to prove who was and was not there.

“It was a riot; nobody was taking attendance,” Segal added. “There was no roll call.”

In fact, for decades, there have been questions about whether or not the longtime director of the Stonewall Veterans Association — a group of New York City people who claim to have been witnesses to the historic 1969 uprising — was there himself.

There have also long been criticisms that the Stonewall uprising was “whitewashed,” with the contributions of people of color largely ignored. Chauncey agrees with this critique. In fact, Chauncey said the uprising happened precisely because of the diversity of the crowd.

“You had a lot of people of color, drag queens, underage street kids who had already dealt with the police a lot and were often much fiercer in dealing with policing than white middle-class college students or business people would have been,” he said.

“Middle-class, white, gay people normally expected the police to protect them as part of their class and racial privilege, but they were marginalized and criminalized because they were gay, and that was always a contradiction to them that a lot of them didn't really know how to manage,” Chauncey continued. “So the Stonewall erupted in part because of who was there. These are precisely the people who have been fighting the police before."

Many have credited iconic black transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson with “throwing the first brick” (or shot glass or stone) during the historic rebellion. But in an audio interview with historian Eric Marcus for his “Making Gay History” podcast, Johnson herself claimed to have not arrived until the uprising was well underway.

“I was uptown and I didn’t get downtown until about 2 o’clock, because when I got downtown the place was already on fire,” Johnson said of the Stonewall Inn. “It was a raid already. The riots had already started.”

There’s even disagreement regarding how many nights the uprising actually lasted.

One Stonewall veteran, Fred Sargeant, said the riots lasted seven days.

“We thought it petered out at around five [days], but then the Village Voice ran an article which was deeply homophobic, and so there was a protest for that article in the same spot where the Stonewall riot occurred, so they all kind of blended together.”

Segal claims there were only four days of actual rioting, and after that there were simply daily “meetings” held by the newly formed activist group Gay Liberation Front.

“There wasn't a day we were not on this street,” he said of Christopher Street, where the Stonewall Inn sits. “So if people were to say we were here for seven days, that's fine.”

“I would say we were here for the next 365 days,” Segal added. “This was our street. This was our home. We told the police it's now ours.”

While the Stonewall uprising is often credited with being the start of the gay rights movement, there was a nascent but growing movement for at least two decades prior, as NBC News has previously reported.

While Stonewall was a critical turning point in the movement, it was not even the first LGBTQ protest at an establishment where gays congregated. Four years prior to Stonewall, in April 1965, there were pickets outside Dewey’s, a Philadelphia coffee shop, after gay and genderqueer people were refused service.

The following year, at Gene Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco, where many LGBTQ young people gathered, patrons rioted after being refused service.

“At one point, the owner decided to get rid of them hurting his business, so called the cops, and they fought back,” Chauncey said. “There was a huge skirmish there. They threw their water glasses and ashtrays at the cops.”

A year after the uprising at Compton’s — and more than a year before Stonewall — there was a protest at the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles.

But despite not being the first, the Stonewall uprising is still the most famous. And despite the many myths and mysteries surrounding it, Chauncey said the historic event has continued to be influential in the ongoing battle for LGBTQ rights.

“The important thing about Stonewall, and I think the useful thing about Stonewall, is that a lot of people point to it and say, ‘We can't stay quiet. We can’t acquiesce. We have to fight back against anti-queer policing and the dominant society.’” he explained. “And as long as that's what Stonewall means to people, and it inspires people to fight, then Stonewall is serving a useful political purpose.”

Editor's note: All four episodes of "Stonewall 50: The Revolution" will be posted to nbcnews.com/nightlyfilms throughout June. To see more LGBTQ archival images, visit The New York Public Library's "Love & Resistance: Stonewall 50" page.