The Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday proposed a new rule for nutrition labels on packaged food and drinks that’s intended to help people make healthier choices at a glance.

Under the proposed rule, which shoppers could see as early as 2028, food manufacturers would be required to display levels of saturated fat, sodium and added sugar on the front of the packaging, in addition to the standard nutrition labels on the back.

Packaged foods in the United States often come with a number of health and nutrition claims, which can make it confusing for consumers to know what’s good or bad for them, said Lindsey Smith Taillie, a nutrition epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Fruit drinks, for example, may advertise high levels of vitamin C on the front of the bottle, making them seem like a healthy choice, but at the same time, they are loaded with added sugar, Smith Taillie said.

The idea is that by placing certain nutrition information directly in front of consumers, they’ll be more likely to make health-conscious decisions.

"We believe that food should be a vehicle for wellness, not a contributor of chronic disease," Rebecca Buckner, the FDA's associate deputy director for human food policy, said on a call with reporters.

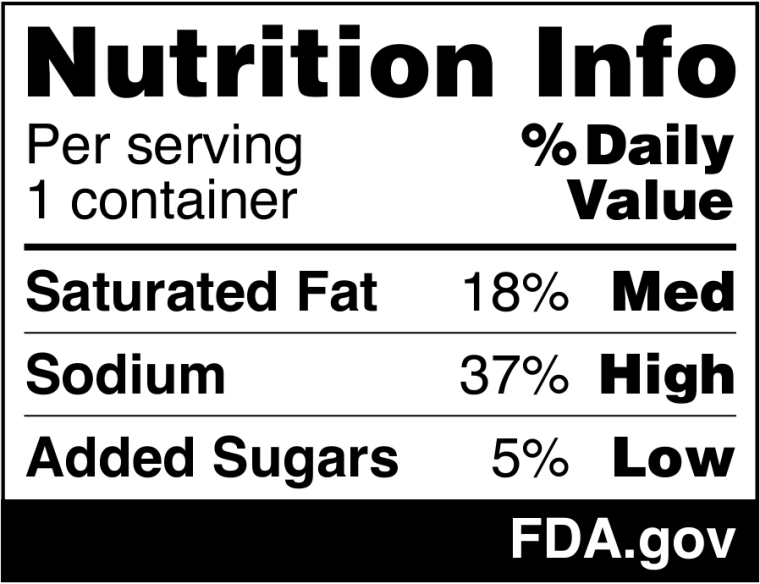

The FDA's proposed front-of-package label would include the amount of saturated fat, sodium and added sugars and whether those amounts are considered "low," "medium" or "high."

FDA officials said the label it landed on was backed by science, including a body of research, consumer focus groups and an agency-led study of nearly 10,000 adults that looked at how people responded to several possible designs.

Saturated fat, sodium and added sugar were chosen as the three nutrients because research shows they're leading contributors to chronic disease, including cancer, heart disease and diabetes, Buckner said.

“I think people want to know this information to help them make good decisions,” said Dr. Yian Gu, a nutrition epidemiologist at the Columbia University Medical Center in New York City.

The extra information won’t do much good if people aren’t aware of how certain nutrients, such as saturated fat, can affect their health, Gu said, adding that more work needs to be done on educating people about their nutrition.

The FDA proposed the labels amid high rates of diet-related chronic diseases, such as Type 2 diabetes and heart disease, in the United States. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for 1 in every 5 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 1 in 10 people have diabetes, mostly Type 2 diabetes. And about 2 in 5 adults have obesity, the CDC says.

“These diseases are not coming from nowhere,” Gu said. “If people are not aware of the science behind all of this nutrition, they will not pay attention to it.”

The front-of-package labels wouldn’t go into effect immediately, according to the FDA. The proposal includes a 120-day comment period, after which the agency may make additional changes to the proposal or finalize the new rule.

Large food manufacturers would have three years after the rule is finalized to make the changes to most of their products, the agency said. Smaller manufacturers would get an additional year to implement the changes.

While it’s not the FDA's intention, Buckner said the new food labels could lead food manufactures to reformulate their products so they could move to the "low" or "medium" categories.

The Consumer Brands Association, an industry trade group, has opposed the mandatory labeling, saying the FDA is considering “schemes with arbitrary scales and symbols that could cause confusion among consumers.”

Sarah Gallo, senior vice president of product policy at the Consumer Brands Association, said in a statement that the group has instead pushed the FDA to collaborate on industry-led initiatives, including Facts Up Front, which allows food manufacturers to voluntarily summarize important nutrition information — such as calories, saturated fat, sodium and added sugars — on the front of packaging. The industry has also introduced SmartLabel, which allows consumers to access detailed nutritional information via QR codes, Gallo said.

Will the labels affect consumers’ habits?

Putting nutrition labels on the front of packages isn’t a new concept — at least outside of the United States. Dozens of countries, including the United Kingdom, Mexico, Chile, Australia and New Zealand, have implemented similar measures.

In 2016, Chile introduced mandatory labels on the front of packaging, alerting consumers to high levels of sugar, saturated fat and other potentially harmful ingredients.

In 2022, Brazil also implemented mandatory front-of-package labels for products.

Colleen Tewksbury, an assistant professor of nutrition science at the University of Pennsylvania, said research has found that the labels do influence what people buy in those countries.

However, she said, the findings may not easily translate to the United States, where “individualism” prevails and consumers don’t “want to be told what to do.”

Often, she said, the people who change their buying behaviors were the ones who were already looking to make changes.

“Research is relatively clear that having very simplistic front of packaging labeling does catch people’s attention, but the second step to that is whether or not it changes purchasing behaviors,” Tewksbury said. “We really don’t know if it’s going to fully impact people’s purchasing habits.”

Smith Taillie, of the University of North Carolina, questioned whether the new label would help people make healthier choices, noting that the design looks similar to what's already found on the back of food packaging.

She also said the front-of-package label could cause confusion among shoppers by including daily value percentages and a low-to-high ranking system.

“A ‘low’ in sugar label on a product that does not typically contain sugar anyway may lead consumers to think a product is healthier than it is,” she said.

What’s more, she added, items that come in small portion sizes — like salty potato chips — are unlikely to get the “high” designation, also giving people a false impression about their healthiness.