Severe, possibly life-threatening strep infections are rising in the United States.

The number of invasive group A strep infections more than doubled from 2013 to 2022, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published Monday in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Prior to that, rates of invasive strep had been stable for 17 years.

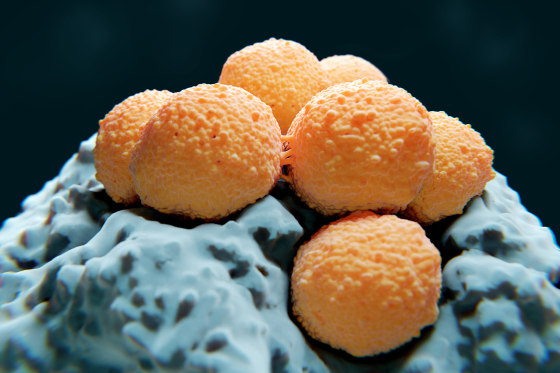

Invasive group A strep occurs when bacteria spread to areas of the body that are normally germ-free, such as the lungs or bloodstream. The same type of bacteria, group A streptococcus, is responsible for strep throat — a far milder infection.

Invasive strep can trigger necrotizing fasciitis, a soft tissue infection also known as flesh-eating disease, or streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, an immune reaction akin to sepsis that can lead to organ failure.

“Within 24 to 48 hours, you could have very, very rapid deterioration,” said Dr. Victor Nizet, a professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Cases can transition from “seeming like a routine flu-like illness to rushing the patient to the ICU, fearing for their recovery,” he added.

The data came from 10 states, with roughly 35 million people total, that track the infections.

In 2013, around 4 out of 100,000 people were diagnosed with invasive strep. By 2022, that rate had risen to around 8 out of 100,000. The number of cases rose from 1,082 in 2013 to 2,759 in 2022.

The study identified more than 21,000 total cases of the infection over the nine-year period, including almost 2,000 deaths.

“When you see this high number of deaths, extrapolate that across the country — we’re probably well into more than 10,000 deaths,” Nizet said.

Dr. Christopher Gregory, a CDC researcher and an author of the study, said the threat of invasive strep to both the general population and high-risk groups has “substantially increased.”

The study calls for “accelerated efforts” to prevent and control infections. It also offered a few possible explanations for the rise in cases.

First, rising rates of diabetes and obesity, among other underlying health conditions, over the study period made some people more vulnerable to invasive strep. Both diabetes and obesity can lead to skin infections or compromise the immune system.

Second, invasive strep is increasing among people who inject drugs, which can allow the bacteria to enter the bloodstream. Infections have also increased in people experiencing homelessness — in 2022, the rate of infections among this population was 807 out of 100,000. Gregory said the rate was “among the highest ever documented worldwide.”

Finally, strains of group A strep appear to be expanding and becoming more diverse, which could create new opportunities for infection. Strains that have expanded in recent years seem more likely to cause skin infections than throat infections, according to the study.

Those strains may also be driving resistance to antibiotics used to treat certain cases of invasive group A strep, macrolides and clindamycin. While penicillin is the go-to antibiotic to treat strep infections, it can be used in combination with clindamycin to treat toxic shock syndrome, and doctors sometimes prescribe a macrolide if a patient has a penicillin allergy.

Overall, the study found that the rate of infections was highest in adults ages 65 and older, and rose in all adults from 2013 to 2022. But it did not detect an increased rate in children.

“That was, to me, the most shocking part of the study,” said Dr. Allison Eckard, division chief for pediatric infectious diseases at the Medical University of South Carolina. “Because clinically, we really are seeing what feels like an increase.”

In late 2022, there were widespread reports from children’s hospitals of a spike in pediatric cases of invasive strep. The CDC issued an alert at the time, noting a possible link to respiratory viruses such as flu, Covid and RSV, which can make people susceptible to strep infections.

Eckard said pediatric cases have also started to look different in recent years.

“We are just seeing more severe cases, more unusual cases, more necrotizing fasciitis, and cases that do raise concern that there is something going on more nationally,” she said.

Eckard added that more research should explore whether certain strep strains are becoming more virulent, or if severe strains are becoming more prevalent.

Doctors said the rise in group A strep infections also points to the need for a vaccine, especially given the rise in antibiotic resistance. However, Nizet questioned whether that would be feasible now, with top vaccine scientists leaving the Food and Drug Administration.

“The lack of vaccine is devastating,” Nizet said. “Of course, we’re concerned about the turn of attitudes at the FDA and the CDC that seem to be putting some sticks in the spokes of the wheel of vaccine development.”