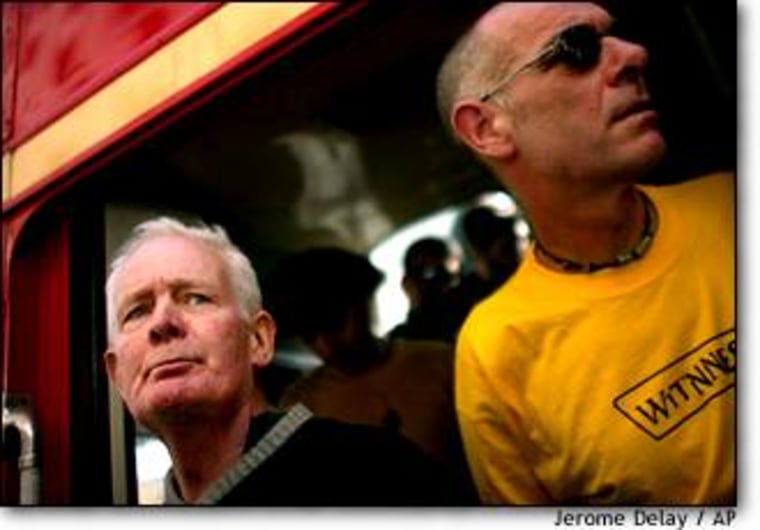

Looking out from the top of a red double-decker bus careening through Baghdad, American antiwar activist Ken O’Keefe sees the whole world as on his side. “How can The New York Times say Iraqis are hoping for war?” asks the California-born veteran of the Persian Gulf War, busily videotaping himself with a minicam, “How do you explain all those Iraqis waving and clapping out there?”

ON THE STREET, local Iraqis seemed at first startled, then bemused, at the bizarre convoy snaking through their suburbs. Led by buses festooned with peace slogans, Beatles pictures and a panoply of mostly European antiwar activists, the convoy was headed to a power station, where some “human shields” would hunker down to try to thwart possible U.S. bombing. As someone strummed a guitar, a long-haired Turkish hippie, dressed in a patchwork jacket embroidered with tiny mirrors, flashed peace signs out the front window of the bus in between tokes on a marijuana cigarette.

More than 200 international human shields, including at least a handful of Americans, have arrived in Baghdad to protest against a U.S.-led war. Many traveled some 3,000 miles on the two double-decker buses through continental Europe, Turkey and Syria. They say they’ll attach themselves to power facilities, water treatment plants, bridges, hospitals and other installations crucial to civilian life. O’Keefe, the founder of www.humanshields.org, last set foot in Iraq as part of a U.S. Marine unit charged with securing a major highway between Kuwait and Iraq during the gulf war. Now O’Keefe, who has a teardrop tattooed under his left eye—“to represent the suffering in the world”—lives in Hawaii rescuing marine turtles. “I don’t let fear dictate my life,” he says, “I’m more fearful riding a big wave in Hawaii than I was in combat.”

For peace activists worldwide, from Finland to Mount Fuji, all roads lead to Baghdad. Antiwar pilgrims have ranged from professional peaceniks to a papal envoy, from Hollywood “bad boy” Sean Penn to former Russian prime minister Yevgeny Primakov. Even German beauty queen Alexandra Vodjanikova, 19, flew into Baghdad last week in hopes of meeting the Iraqi president. “I’m just a little girl, but I hoped to ask Saddam Hussein to cooperate with the weapons inspectors,” says Miss Germany, barefoot and wearing a low-cut rust-colored pantsuit during a breakfast interview with NEWSWEEK. “Madonna did her video clip, and other people are doing street protests. I’ll do what I can.” On Wednesday, the beauty queen left Baghdad without a presidential audience, but she did have a protracted meeting with Hussein’s son Uday. The hit parade of celebrities may be just beginning: Winnie Mandela, former wife of South Africa’s Nelson Mandela, is among those expressing an interest in joining the peace cavalcade.

The activists’ tactics are as diverse as the personalities. This week, 17 Spanish antiwar activists “liberated” the Spanish embassy in Baghdad, which had been evacuated by its diplomats two weeks earlier. The only occupant left was a smiling Iraqi gardener who let the peaceniks in without a fight; he seemed pleased that some Spaniards—any Spaniards—had returned to the diplomatic mission. The peaceniks didn’t tamper with the locked file cabinets in the embassy, but they did use its photocopying machine to duplicate their manifesto. They also hung up a banner reading NO SANCTIONS, NO WAR on the white stucco building.

The most exotic subculture is the world of the human shields, who say they’ll put their lives on the line by living at vital Iraqi installations. At least temporarily, their number included a St. Bernard search-and-rescue dog named Gustavo, who came with a group led by Canadian grandmother Roberta Taman. Taman made a 4,000-mile overland journey from France to “wrap our arms around Iraq and say no to war.” She left Baghdad in mid-February to join her husband in Albania, where she’ll “garden for peace.” Gustavo, for his part, had to relinquish the tiny brandy keg customarily attached to his collar because Iraq’s religious laws frown on alcohol.

This week, the shields began “deploying,” as they called it, to various locations. On Wednesday, a group bedded down at the Daurra oil refinery in Baghdad. Earlier, a multinational group arrived at a water-treatment plant where the Italians among them immediately began cooking pasta. On Sunday, 15 would-be shields set up camp at the Baghdad South Power Station, which was largely destroyed in 1991. “I want the world to know there’s no such thing as collateral damage,” said O’Keefe after activists had set down their backpacks and bedrolls on metal beds laid out dormitory style in a plush conference room featuring at least a dozen likenesses of Saddam Hussein. “If anyone here dies due to bombing, it’s murder.”

A gray-haired member of the group, Godfrey Meynell, then took the floor to deplore war, international capitalism and global warming. Another British citizen, a professional eco-activist known as “Muppet Dave,” a.k.a. David Howarth, is a hardened veteran of half a dozen guerrilla-style U.K. environmental protests. (In one of them, he lived for weeks in a tunnel under the Manchester airport runway.) Was he ready to die? “Every day people die from pollution, from global warming, from getting run over on the highway. More people died in 1991 from dirty water than from bombing; that’s one reason I want the electricity to stay on so that water and medical facilities will continue,” says the peace activist, whose tattoos and eyebrow rings fascinated Iraqis.

One Iraqi power-generation official, Ihsan Obeidi, seemed appreciative—if a bit overwhelmed—by the circuslike environment that eclipsed the plant’s towering smokestacks and power transformers. “We have a bomb shelter here. We’ll bring the shields to the shelter if there is an attack,” he says, ignoring the paradox of trying to save the lives of those who had converged here precisely to risk them.

This festive, almost surreal, scene is a stark contrast to Iraq’s detention of 2,000 foreigners during its 1990 invasion of Kuwait. Many of the captives were expatriate technicians and foreign oil workers; most were transported to Iraq, where some were held at missile bases, oil refineries and other strategic facilities as part of Baghdad’s efforts to prevent a U.S.-led assault. Iraqi authorities were harshly criticized for holding hostages—whom they euphemistically called “guests.” The foreign detainees were released before the gulf war began. At the same time, a small number of volunteer human shields came to Iraq. But they were kept at an isolated “peace camp” and had little impact on international public opinion, which largely favored a military solution.

Now the international mood is much different. Public and official sentiment in the West remains starkly divided. And the Baghdad government has shown a savvier approach. For most human shields, their Iraqi odyssey includes one early stop at a whitewashed Ottoman-era palace in old Baghdad. This is the headquarters of the Organization of Friendship, Peace and Solidarity, headed by former minister and diplomat Abdul-Razzaq Al-Hashimy. His organization provides accommodation and meals for the shields at several small Baghdad hotels, replete with international telephone lines and free Internet service. It also provides a list of facilities prepared to host the shields.

Al-Hashimy is a combative supporter of the regime who speaks perfect English. He insists all the shields are volunteers. (“Do they have a death wish? Ask them!”) In an interview with NEWSWEEK, he spent much of the time cracking satirical jokes blasting U.S. President George W. Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair. “Why don’t they attack North Korea? Because Pyongyang has no oil and no Israel. This all convinces me that President Saddam Hussein is the right man for Iraq.”

The human shields may not be able to thwart a war. But they have attracted official attention. U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld last week warned Baghdad that the Iraqi government’s support for lodging civilians near potential targets is “a crime against humanity.” “Deploying human shields is not a military strategy,” said Rumsfeld. “It’s murder.” Human-rights advocates adopted a more evenhanded approach, condemning both sides for their respective attitudes. “If Iraq uses people as human shields, that is a war crime,” says Kenneth Roth, head of the U.S.-based Human Rights Watch, ”[But] if the United States attacks targets that are shielded by civilians without demonstrating an overwhelming military necessity to do so, that would be a war crime, too.”

Some of the shields seemed to be just now waking up to the complex issues—and the risks—swirling about them. “I’m trying to meet with [U.N. weapons inspectors] to make sure the sites we’re stationed at aren’t close to legitimate military targets,” says one Western peacenik on condition of anonymity. Both the Baghdad South power plant and the Daurra refinery are close to military sites or VIP palaces, and “a handful” of shields were beginning to worry they’d be forced to stay in places where they didn’t want to be, he said. “There’s a rumor going around that when we want to leave Iraq, some might not be allowed to.” At least for now, Iraqi authorities show no sign of adopting such tactics. More likely, they’ll reap the propaganda windfall that the human shields represent—then send them home if they’re no longer useful.

© 2003 Newsweek, Inc.