The looting and scattered violence that accompanied the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime should not be surprising and will not last much longer. A far more important issue for Americans to ponder is this: Having sent the world’s most professional military to win the war, would it really be wise to turn the responsibility for securing the peace over to the United Nations, or even the U.S. State Department?

Many of the scenes playing out on the streets of Baghdad, Basra, Kirkuk and Mosul are a confirmation of almost everything the Bush administration claimed about how the Iraqi people would respond to Operation Iraqi Freedom. Joyous mobs, giddy with the intoxicating effects of their new-found freedom celebrating and blessing George Bush.

At the same time, there is widespread looting — I prefer to refer to this as “redistributive justice” — taking place as each city is liberated. Two Shiite clerics were killed by a mob in Najaf in what was reported to be a case of rivalry between pro-U.S. and pro-Saddam factions. There have been several suicide bombings.

Some of the same commentators who just a few days ago were wailing that coalition forces were bogged down and losing the war are now making dire pronouncements regarding the chaos and loss of control in Iraq’s cities. Without even a second’s reflection on the irony, they warn that bringing order to Iraq will be a much more difficult task than the campaign to liberate it. If winning the peace is even three times harder than fighting the war, it will be only a tenth of the challenge the United States and its allies faced at the end of World War II or are currently confronting in Afghanistan.

NOT SO HARD?

In reality, bringing order to Iraq, now that Saddam Hussein’s regime has been defeated, will not pose much of a problem for the coalition. Already the stories of an impending humanitarian crisis must compete for attention with reports of large shipments of food, water and medicines moving into Iraq by sea and truck.

Basra, fully occupied by British forces only a few days ago, is swiftly returning to a semblance of normalcy. A Central Command briefer, Brig. Gen. Vincent Brooks, making reference to an incident in Basra in which a British patrol engaged a gang of armed bank robbers, declared: “They were shot. Looting went down in Basra.”

A dusk-to-dawn curfew has been imposed on Baghdad. Additional ground forces are flowing into the theater to relieve the well-worn 3rd Infantry and 1st U.S. Marine divisions and provide more “boots on the ground.”

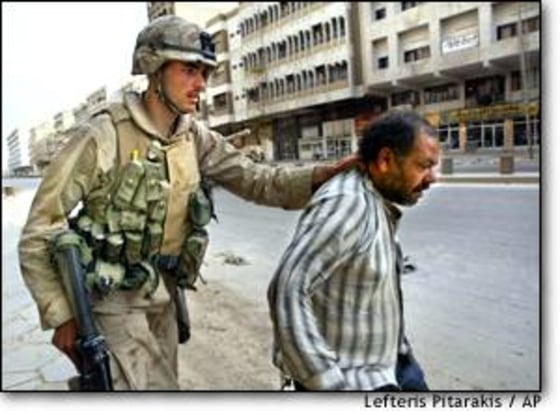

The new rules of engagement issued by Gen. Tommy Franks, commander of the war, reflect the new reality on the ground. Troops are forbidden to use deadly force to prevent looting. They should allow government workers to go to their jobs. Hospitals, businesses and mosques should remain open. Schools should reopen and record attendance. Police, fire and emergency workers should continue to report to their jobs unless told otherwise.

FALSE ALARM

Many commentators have expressed concerns that U.S. troops will be forced into the unfamiliar role of policemen and that this would be a dangerous and inappropriate use of combat forces. In fact, this role is neither unfamiliar nor particularly challenging to U.S. forces. Combat units have been operating as peacekeepers in the Balkans for almost eight years now. It turns out that Abrams tanks, Bradley fighting vehicles and Apache helicopter gunships are extremely useful for maintaining order, particularly when the lawless elements are armed with automatic rifles and rocket-propelled grenades.

The United States has established special peacekeeping-urban warfare training centers in both Louisiana and Germany for units assigned to those missions. The U.S. military has a long and illustrious tradition of performing police duties around the world. British forces will ably assist them. The British almost never miss an opportunity to remind Americans of their extensive experience in urban counter-insurgency in Northern Ireland.

DOWN THE ROAD

The longer-term outlook for Iraq is more problematic. Unfortunately, the analogies to the occupation of Germany and Japan are incorrect. The coalition faces a different problem than that which confronted the victorious Allies after World War II. In both those cases, there was a strong national identity, an single, unifying ethnicity, some halting exposure to democratic institutions and, despite the efforts of totalitarian regimes to stamp it out, a civic culture. The purpose of occupation after World War II was not liberation but control. While “de-Saddamization” of the government, police and military must be on the coalition’s agenda, this activity is less important than the creation of new institutions.

Once order is restored and basic services re-established the coalition must pursue three complementary goals simultaneously. First, the oil must flow in order to obtain the resources with which to rebuild the country. Second, an interim government must be created that is fully representative. It must reflect not only the ethnic divisions in Iraq but, more important, that nation’s various social and economic interests. One of the tasks for this interim government is to call a constitutional convention that will create the basis for a representative government.

Finally, a new Iraqi military must be created, one of sufficient size and capability to protect the nation but not so large as to be a threat to the new government. A critical aspect of this step will be the establishment of strong civilian control of the military. This is one of the most important lessons that the coalition can teach Iraqis.

The rebuilding of Iraq is too important a task to be turned over to the United Nations and too complex to be given to the U.S. State Department. As a result, it will inevitably become a responsibility of the coalition in general, and the U.S. Department of Defense in particular. The critics of this approach need to answer one question: Who else has the capabilities to rebuild a nation?

(Dan Goure is an NBC military analyst who served in the Pentagon during the first Gulf War. He is now senior military analyst of the Washington-based Lexington Institute.)