Although it happened with scarcely a shot fired, the seizure Thursday of Kirkuk by Kurdish forces backed by U.S. special operations forces may not lead to immediate peace in the city. A 5,000-year-old-city amid rich oil fields on a productive agricultural plain in northern Iraq, Kirkuk holds the key to the country’s future prosperity. But it also contains all the elements for a “war within a war” that could draw other nations into the 3-week-old conflict.

Hundreds of thousands of Kurds, and far fewer numbers of Turkoman and Assyrian Christians, were ethnically cleansed from the city and hundreds of nearby villages by Saddam Hussein over the past 30 years.

Now, they are anxious to go reclaim the homes, farms and businesses, which were given to Arab settlers by Saddam’s regime. Violence is possible if the settlers do not voluntarily leave quickly.

Turkey has threatened that if the Kurds — who see Kirkuk as the symbolic center of Iraqi Kurdistan — retain control of the city, Ankara could send up to 40,000 troops across the border to confront the “peshmerga” fighters.

The Kurds, for their part, have said they would view a Turkish incursion as an invasion and would fight. Iran has also said Turkish interference could trigger their own incursion.

A variety of steps need to been taken to avoid this worst-case scenario.

TURKEY’S FEARS

Turkey’s policy in Iraq in the past decade has been to ensure that the Iraqi Kurds do not achieve a stable autonomy that might serve as a model for Turkey’s Kurdish population.

More then 20 percent of Turkey’s population is Kurdish, though Turkey has long denied their ethnic distinctiveness, calling them “mountain Turks.”

Ankara has fought a brutal war against a Kurdish independence movement for 15 years in mainly Kurdish southeastern Turkey.

Iraqi Kurds, however, since the 1958 founding of the Iraq republic, have called not for independence, but rather for autonomy or federal status within the Iraqi state.

Still, Ankara fears this war could open the way for its Kurds — empowered by control of oil-rich Kirkuk — to make a bid for an independent state.

Ahead of the U.S.-led war, Turkey refused to allow 62,000 American troops transit across Turkey to open a northern front in Iraq. Paradoxically, at the same time, Turkey expressed fear that without large numbers of U.S. troops, a power vacuum would be created in northern Iraq that Kurdish forces would fill.

The United States scrambled to persuade both Turkey and the Iraqi Kurds to refrain from making unilateral moves. Ankara finally said in early April it would not intervene — unless its national security was threatened. But it agreed to work under U.S. military authority.

On Thursday, Secretary of State Colin Powell said he had reached an accord with Turkey to have Kurdish forces pull back from Kirkuk. At the same time, the United States agreed that Turkey could send a small group of monitors to Kirkuk.

Kirkuk “will be under American control,” White House spokesman Ari Fleischer said.

U.S.-KURDISH COOPERATION

Ahead of the war, a U.S. military liaison and coordination command was established in northern Iraq to bring the more then 60,000 Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga fighters under the coalition umbrella.

Up to 3,000 U.S. troops are now in Iraqi Kurdistan and planeloads of tanks, heavy weapons and armored personnel carriers continue to land nearly daily at two airstrips.

The first U.S.-Kurdish joint effort, to rout the radical Islamic group Ansar al-Islam from its mountain stronghold along the Iranian border, was touted as a huge operational success by U.S. special operations forces.

This cooperative action paved the way for a closer working relationship between U.S. and Kurdish forces. Along the 260-mile long demarcation line between Iraqi Kurdistan and government-controlled Iraq, U.S. special operations forces, working with Kurdish intelligence, call in air strikes against Iraqi troops, pounding their positions,

In the past week, Iraq has abandoned one checkpoint after another along the northern front.

As the Iraqis fell back from the line toward Kirkuk, Kurdish peshmerga moved in to fill the void.

The Kurdish government had repeatedly said recently that it would not make a unilateral move against Kirkuk or encourage an uprising outside of coalition strategy. However, U.S. Central Command was vague Thursday on whether the decision to march on Kirkuk was made by the Kurds or by U.S. special operations forces.

While stressing that the right of return is a “sacred right,” Barham Salih, prime minister of eastern Iraqi Kurdistan, recently said, “We will only move on Kirkuk with Iraqi democratic forces, within the coalition.”

An international commission will be set up to address claims of the Kurds, Turkomans and Christians who were expelled from Kirkuk, he said.

Many of the displaced, languishing for years in the poverty of dispossession in Iraqi Kurdistan, may have gotten the government’s message. “We will go back in an organized way,” said Khalid Neriman, who was expelled from Kirkuk in 1996 when he was a university student. Many also say they are tired of fighting and will not risk their lives to retake the city.

“We will leave it to our government,” Neriman said.

With Saddam’s regime apparently dissolving in Baghdad, it may not require a large force to wrest control of Kirkuk and nearby Mosul, Iraq’s third-largest city.

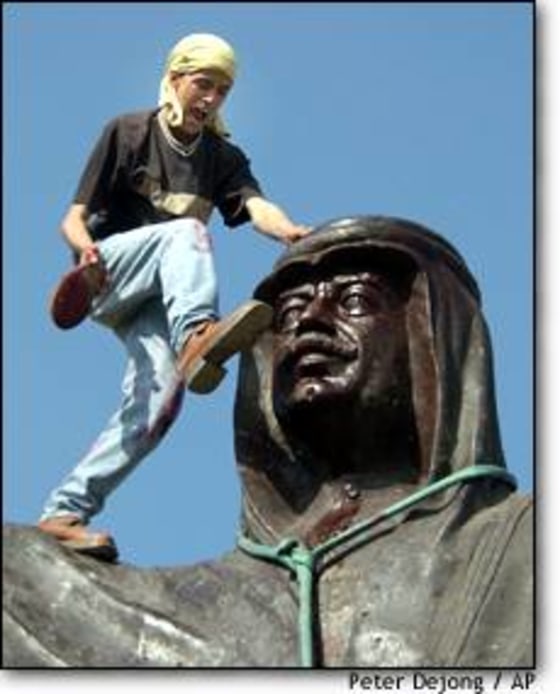

But it remains to be seen if the Kurdish people, in their exuberance over the demise of a hated regime they have fought for 30 years, will be able to resist the urge to rush in and reclaim symbols long denied them by the regime.

And it remains to be seen if the U.S.-Kurdish coalition will maintain control of the situation and hold off a Turkish and Iranian intervention.

(Maggy Zanger teaches journalism at the American University in Cairo and has been conducting research in Iraqi Kurdistan for several years. She is also an NBC news analyst.)