Special operations forces along with CIA operatives are spearheading the advance of U.S. forces in northern Iraq. According to U.S. officials on Monday, the elite teams — working closely with Kurdish forces — are within a few miles of Kirkuk, Iraq’s third-largest city, and they have already taken control of the prized oil fields. The stealthy advance highlights the huge role the special operators are playing in the war against Saddam Hussein.

Special Operations Forces, an umbrella term for the Delta Force, Green Berets, Navy SEALs and Army Rangers, have been based in northern Iraq for months, working closely with the CIA’s Special Activities Division.

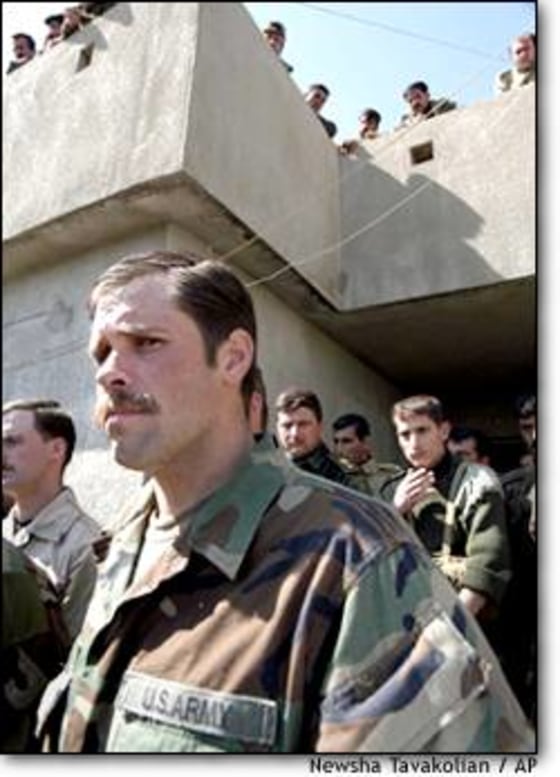

Together with British and Australian SAS troops and Polish “GROM” commandos, these operators have build close ties with Kurdish leadership and the local “peshmerga” fighters to pave the way for official opening of the “northern front” last week with the arrival of the 173rd Airborne Brigade at Harir air base.

Local leaders were won over, airstrips were graded and improved, and local guides and interpreters were assigned for the paratroopers, whose ranks now number around 1,600 in the Kurdish-run territory.

The essential role in establishing the front and pushing toward Kirkuk underscores the important role special operations forces will play in this war, unlike Operation Desert Storm.

In 1991, the special operations force was employed late and not to its full capability in part because Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf, who ran the coalition campaign against Iraq, was understandably concerned that behind-the-lines activity might have alerted Baghdad to the dangers on Iraq’s flanks.

What has changed? Why are these elite forces being employed early and often in this conflict?

Special operations are by nature risky. They rely on surprise and shock for the combat edge — when they work, it can give the campaign a huge advantage. But when they fail, it can be ugly.

It takes resolve and backing at the highest levels in the Pentagon and White House to authorize these risky operations, and the elite force is getting that now. From President Bush to Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, special operations are not only supported, they are being encouraged.

AFGHANISTAN ACHIEVEMENTS

Undoubtedly, the special operations forces’ impressive accomplishments in Afghanistan have contributed to this trust and confidence.

A handful of special operators working with their CIA comrades turned around a demoralized Northern Alliance in days — winning the confidence of the anti-Taliban force as they delivered awesome air power to crush the government units.

Many of these same Army, Navy and Air Force operators are now in the Persian Gulf region. They are experienced, psychologically ready and have been in the field for months. They are known quantities, and their commanders, like former Delta Force commander Gary Harrell, are in key positions. Conventional commanders, beginning with Gen. Tommy Franks, know and trust them.

The strategic objective this time requires their language and cultural skills. This operation is about regime change and reconstruction, as distinct from the limited mission of the last Gulf War — to eject the Iraqi army from Kuwait.

NORTH AND SOUTH

The special operation teams, once again working closely with their CIA comrades, are throughout Iraq.

In addition to the north, operatives have infiltrated Iraqi society in an effort to induce wholesale defections of key Iraqi political and military leaders while also building a relationship with the Shiite opposition in the south of the country.

The members also are conducting reconnaissance and surveillance operations on high-value targets, which include key personalities, the oil fields, command and control facilities, and air defense sites.

As the war rolls on, you can expect the special teams to attack these targets, kill key members of the regime and provide terminal guidance and human eyes on the target for battle-damage assessment.

Furthermore, the U.S. Army Rangers have seized key airfields in western Iraq that will become a base for all operations in the old Mesopotamia region of the Euphrates River valley, and Navy SEALs working in concert with Royal Marine Commandos led the assault to seize strategic off-shore oil terminals and the approaches to the al-Faw peninsula and the Rumeila oil fields. Polish Special Operations forces, the GROM, participated with Navy SEALs and British Special Boat Service (SBS) in an operation early in the war to secure off shore oil platforms.

AFTER THE WAR

Special operations forces’ utility will continue following hostilities. Special ops civil affairs and psychological operations units will coordinate international relief at the grass-roots level, aiming to gain the support and trust of the Iraqi people for the effort.

Special operations forces units may well be involved in the hunt for lower-level figures in the Iraqi regime. They will also train and equip new Iraqi military units.

Of course, they must still continue fighting the U.S. global war on terrorism. Their greatest challenge may be getting some rest between these intense and risky engagements.

The special operations forces are a small, select group of warriors who take years to train. You cannot create more of these units overnight no matter how badly you need them.

(Retired Gen. Wayne Downing was commander of a joint special operations task force assigned to U.S. Central Command during Desert Storm.)