On Monday, it will be 2 1/2 years since a Chinese fighter played chicken with a U.S. EP-3 spy plane over the South China Sea and lost. The ensuing crisis, which featured a captive plane and crew and coming as it did on the heels of China’s successful stealing of American nuclear warhead secrets, struck many as a preview of a century of Sino-American competition to come. Since the 9/11 attacks, American attention turned toward the Islamic world and the threat posed by religious fervor run amok, and that suits China just fine.

Perhaps no other country on earth has found as much to be happy about in the post-Sept. 11 world as China. The war on terrorism, and America’s need for cooperation from any nation that will offer it, has provided shelter from the normal frictions that a large, rising communist power would experience in its dealings with the United States. China, in turn, has moved to take advantage of this in many ways. In some instances, like rapid economic expansion, this has been largely a matter of momentum. In others, like its crackdown on ethnic Muslims inside China and its alleged nuclear cooperation with Pakistan, are the source of concern in Washington.

On the other hand, China provided significant assistance to the U.S. effort against the Taliban and al Qaida, groups it, too, counts as enemies. It joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, requiring it to meet new standards for transparency and market access. Most recently, China finally dropped its rhetoric about “non-interference in other nation’s affairs” and pushed North Korea into multinational talks on nuclear weapons that began Wednesday in Beijing.

So the atmosphere is dramatically different - a world away, even - from the hostile rhetoric and barely veiled threats of April, 2001, when, in the words of Rep. Tom DeLay, the Republican Whip of the House, the spy plane affair showed “the reckless, ruthless, and irrational mindset of China’s Communist government.”

Compare DeLay’s words with the praise that one of the administration’s leading hawks, Secretary of State John Bolton, had for China during a visit last month in which he thanked Beijing for its help on North Korea: “I think the Chinese government has devoted a lot of attention and effort toward the question of getting multilateral negotiations underway. We’ve considered those efforts very important, and I’m not sure that there is anything else specifically that we could think of that the government here could do that they haven’t already tried.”

Emerging power

While America may be distracted, nothing that has happened since Sept. 11, 2001 has altered the basic debate over China that has been raging in American foreign policy circles for over two decades. Is China an awakening communist giant bent on dominating Asia and challenging America militarily, or is it a liberalizing country slowly shedding communism and bound to be a reliable trade and diplomatic player well before it can stand toe-to-toe with America?

The data will support either argument, if one is inclined to use data selectively.

American China hawks, primarily on the Right, cite China’s successful nuclear espionage efforts at Los Alamos, its continued repression of human rights and its designs on Taiwan as evidence that this is an enemy in the making.

The internationalist Left in America sees China as the Right’s convenient excuse for continuing to build strategic weapons, including a new ballistic missile shield and a proposed new generation of nuclear missiles, all unlikely to fend off al Qaida but important to the stock price of American defense contractors.

Taken together, however, most China experts suggest that the jury is out on what kind of nation China is becoming. Several recent studies noted that factions in China’s leadership hope to attain military parity with the United States sometime in the 21st century. Yet even the most hawkish of these panels, the congressionally chartered U.S.-China Security Review Commission, says “no one can reliably predict whether relations between the U.S. and China will remain contentious or grow into a cooperative relationship molded by either converging ideologies or respect for ideological differences, compatible regional interests, and a mutually beneficial economic relationship.”

No one offers any credence to the idea that China, outside of being suicidal, presents a military threat to the United States - a common assertion only recently. As the Council on Foreign Relations put it in May, “for the foreseeable future, China will be preoccupied with domestic problems-political succession, public health issues, non-performing loans and a potential banking crisis, rising unemployment, growing inequality, and corruption. To address these domestic concerns, China’s leaders need a peaceful international environment in general and good relations with the United States in particular.”

China's military power

But China, hawks contend, is engaged in an enormous military buildup, underscored by the deployment of surface-to-surface missiles along the coast facing Taiwan, the democratic island-state that broke away in 1949 but which Beijing still claims. Last August, discussing those missiles, U.S. Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz said “I don’t see that building up your missiles is part of a fundamental policy of peaceful resolution.”

Yet Wolfowitz and other defense and military officials do not go so far as to paint China as the enemy. The Bush administration’s term — “strategic competitor” — wsa meant to distinguish Bush policy from Clinton’s “strategic partner.” But the distinction basically disappeared with the trade center towers.

Statistically, China ranks 4th in the world in annual defense spending at $47 billion, that is dwarfed by American spending in excess of $400 billion.

Further, the more China’s spending is examined, the less impressive it becomes. China starts from a very low standard, fielding weapons systems that barely match the standards of the 1980s U.S. military. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), impressive on paper at 2.9 million troops, is deliberately inflated to prevent young men from swelling the ranks of those unemployed by the introduction of market forces into China’s economy.

Perhaps the most telling indicator of China’s military power was an internal “White Paper on National Defense” commissioned by the PLA in 2000 that spoke frankly about prospects for closing the gap with America’s military. Its authors assert that U.S. relative power - the gap between the United States and all other states - would remain constant, if not actually increase, in the coming decades.

Alastair Iain Johnston, a China expert at Harvard University, wrote recently that “in practice this means that [China] cannot realistically think of replacing the United States as the regional hegemon.”

The economy, perhaps, stupid?

American economic nationalists wield their own statistics, and in many ways they are more convincing. Even if China cannot threaten the United States militarily over the next thirty years, will there be a blue collar job market in America in the meantime?

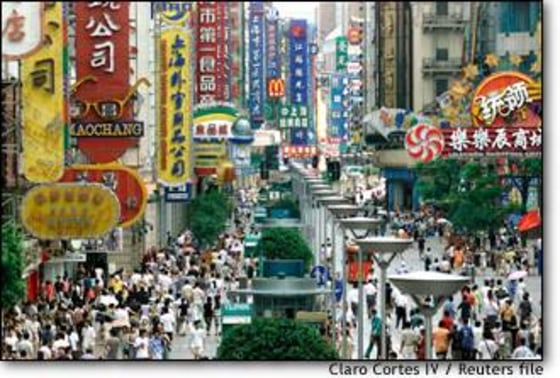

No one who examines the statistical data can doubt that China will pose a major challenge economically to the United States in the coming decade. China’s economy continues to grow at a pace that defies even bullish analysts.

Though official statistics are widely mistrusted and China’s internal poverty rate is far higher than it admits, the consensus is that China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by 5-to-8 percent in 2002 and is likely to match that level in 2003 and 2004. Moreover, this is a pace it has maintained for over a decade.

That already makes it the sixth largest economy in terms of output in the world, and one growing at a rate that will put it firmly into third place (surpassing Germany) by 2008 and on track to matching No. 2 Japan in the second decade of the new century. Economists are quick to note that China has to grow by 2 to 3 percent simply to create enough jobs for its growing population.

Still, China is booming, and the economic displacement its growing power will cause already has the world’s industrial giants worried. “Asian Tigers” like South Korea, Thailand and Singapore already have seen manufacturing jobs they stole from the West shifting to even cheaper China.

Japan is concerned that its electronics industry may also suffer. Already making more than half the worlds footwear, sporting equipment and toys, China is poised to move in on the high value retail market in a new way: with its own brands. Electronics companies like Panasonic and Seimens and Sanyo, who so far have contracted Chinese labor to build their brands cheaply, may soon find their DVD players and car stereos facing competition from China’s own brands. Last year, one such company — Apex — entered the U.S. market via marketing deals with Wall-Mart and other major distributors and outsold every other brand except Sony.

The American Textile Manufacturers Institute earlier this year launched a ”China Threat Initiative” to build support for tariffs that would protect what is left of the U.S. textile industry.

China’s own huge and growing middle-class, with India’s, also will become increasingly important in setting tastes and trends. General Motors, for instance, expects China to become the world’s largest market for cars by 2025.

None of this, of course, means that China will be the next Soviet Union, though it doesn’t rule it out, either. Predicting either option remains a matter of opinion. What is for certain is that America’s Sept. 11 tragedy and the wars that followed have granted China a respite from the cyclical ideological frictions and diplomatic clashes that divert attention from its own long-term interest: growing into a stronger, more prosperous and influential nation. How that squares with American interests remains to be seen.