Three foreign powers — the United States, Britain and France — are moving in different ways to re-establish the spheres of influence in Africa they abandoned at the end of the Cold War. With the United Nations struggling to muster the resources and political consensus needed to tackle the continent’s many ills, these three nations are moving, somewhat reluctantly, to prevent Africa’s most poorly governed states from breeding epidemics, refugee flows and terrorism that could threaten the West. Indeed, France and the United States, rivals for influence in many parts of the world, have found common ground in Africa.

While American attention is focused on President Bush’s five-nation tour of the continent, he is actually the last of the leaders of these three Western powers to tour Africa this year promising new aid and assistance in return for economic reforms and military concessions.

British Prime Minister Tony Blair and French President Jacques Chirac made their own swings through Africa earlier this year, each focusing on the crisis most central to his nation’s historical interests, each dispersing and trumpeting aid packages put together by the rich nations of the European Union.

For Blair, the focus was the fragile democracies once ruled by Britain — Nigeria and Kenya — and Zimbabwe, a formerly prosperous nation being run into the ground by Robert Mugabe.

For France, the focus is French-speaking former colonies in West Africa, as well as the Francophone former Belgian colony in Congo, site of a cataclysmic war that has claimed some 2.5 million lives since 1997.

Increasingly, officials and Africa experts say, Britain, France and the United States are on the same page when it comes to Africa, at least in terms of security issues. While Paris and Washington remain wary of each other elsewhere, a U.N. diplomat says, “it has dawned on them that, as the two countries with the greatest influence in Africa, they have an enormous interest in coordinating whatever attention they can pay” to the continent.

Examples are not hard to find. U.S. special operations forces and other units have been hosted at the French base in the East African nation of Djibouti since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, using them to project power into Somalia, Kenya and Yemen.

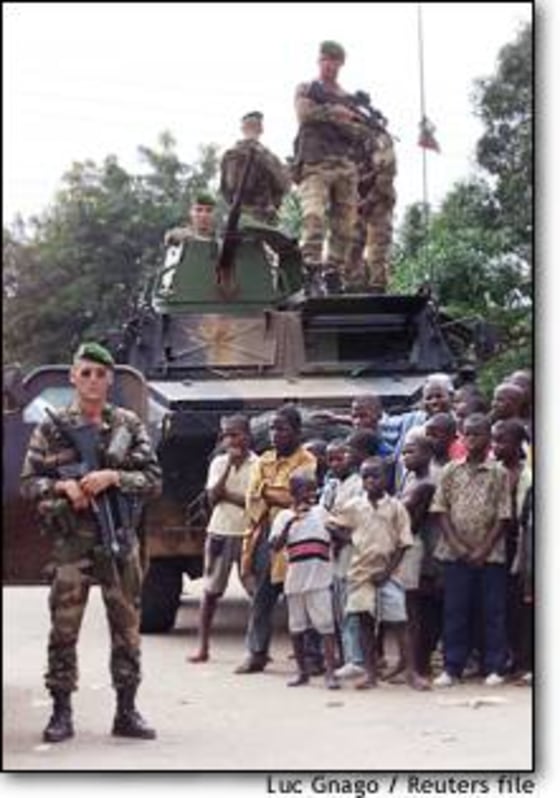

Earlier this year, Britain and France both intervened in restive former colonies to prevent fragile governments from being overrun by rebel movements. At the urging of Paris and London, the United States appears to be on the brink of doing the same in Liberia, the one African state it can claim a quasi-colonial relationship to. In all three cases, officials say, there have been intensive consultations and efforts to coordinate positions.

Even as Washington fumed at French diplomacy on Iraq back in February, for instance, the State Department’s top official on Africa, Deputy Secretary of State Walter Kansteiner, told Congress that Ivory Coast had been saved by “the intervening presence of French military forces.”

On the one great African issue where the two nations disagreed — the war in Congo — the United States on Wednesday officially informed U.N. diplomats that it would drop its objection to the expansion of the peacekeeping force there now that French troops have intervened and demonstrated that a professional force can pacify at least some part of the country.

The United States has no intention of participating with troops. But Washington’s decision to drop its objections to a French proposal to enlarge the U.N. force is seen as another sign of cooperation in a region where the two have been seen as rivals.

Swallowing pride

A few short years ago, British or French troops’ being welcomed back to Africa would have been difficult to imagine.

Mahmood Mamdani, a Columbia University professor who has written on colonialism’s legacy, says the end of the Cold War brought a kind of irrational optimism to the continent.

“Africans thought everything would change, that dictators would be orphaned,” says Mamdani, reached at his home in Uganda. Partly because of this reflex, African support for a U.S. initiative to create a “pan-African peacekeeping brigade” withered and died in the mid-1990s.

There are no such qualms today.

Now, says Mamdani, African leaders are not so quick to refuse outside help. After the genocidal violence of Rwanda in 1994, horrific unrest in West Africa, a war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, and most of all the multinational carnage in Congo, Mamdani says “those who would have objected 10 years ago today have had a big dose of reality since. They know the price paid for grandstanding, and now, even dignity has to be swallowed.”

Liberia swallows hard

On Monday, U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan, himself a West African native of Ghana, is to meet with Bush to press for U.S. troops in Liberia. He will also ask the president to consider another cold, hard fact of Africa’s relationship with the West: The countries of sub-Saharan Africa receive about $55 billion a year in international financial aid yet pay more than $91 billion a year back to Western banks because of a crushing loan burden. And, even as Bush and his big power colleagues talk of generous new trade benefits, the fact is - as The Economist put it last week — the average European cow gets a government agricultural subsidy worth many times more per year than the average income of Africa’s struggling farmers.

Outright debt forgiveness appears to be off the table for now, and farm subsidies are political third rails both in Europe and the United States, particularly with Bush’s reelection looming.

On Liberia, however, Annan may do better. Bush has resisted a firm commitment, but Liberians have thronged the U.S. military assessment team sent to consider the country’s needs this week, and expectations are high that some U.S. force will be approved.

Ending the civil war in Liberia, founded in 1820 by freed American slaves and bankrolled by such early American luminaries as James Monroe and Henry Clay, could be narrowly defined as America’s tending to its “sphere of influence” in Africa.

But officials say the administration believes it cannot take the same geographically based view of Africa as former colonial rulers.

The superpower perspective

Whatever Bush decides with regard to Liberia, where hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. aid has sustained a series of misanthropic rulers over the past several decades, Washington clearly is concerned about the security implications posed by the “failing states” that can be found in every corner of the continent.

Along these lines, U.S. diplomats, often working through contacts supplied by their British and French counterparts, have approached Uganda, Senegal, Nigeria and South Africa about the possibility of obtaining military landing, overflight and refueling rights.

In some cases, a State Department official says, the discussions go beyond such logistical functions “and involve contingency bases and possibly even pre-positioning pacts,” a reference to the kinds of agreements Washington signed with several Persian Gulf states in the early 1990s allowing the military to warehouse supplies for entire brigades — all of which turned out to be vital during the recent Iraq war.

Africa cannot compete for priority with the likes of Iraq or Iran or North Korea. But it does appear to be an area of increasing cooperation among testy allies who are the most influential actors on the African continent. There also appears to be a broad consensus after Sept. 11, 2001, that failed states cannot simply be considered “out of sight, out of mind.” How that translates to action is yet to be seen.