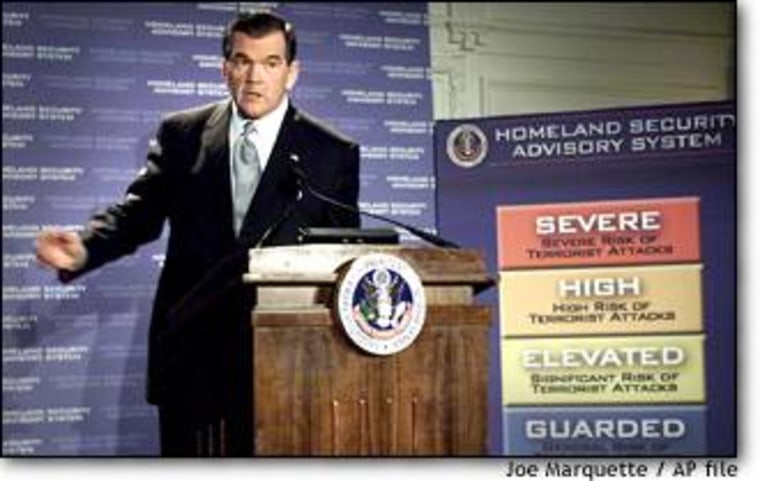

With the nation’s 227th birthday looming next weekend, a debate again is raging inside the federal agencies responsible for preventing domestic terrorism about raising the color-coded “threat” level to “orange” from “yellow.” While no decision has been made and the Homeland Security Department insists that intelligence currently does not warrant such a move, the pressure against doing so this time around is fierce and centered on a simple question: Have the threat level elevations since Sept. 11, 2001, discredited the system in the eyes of the American public?

The Homeland Security Department is quick to point out that no specific and credible intelligence has emerged to suggest that a terrorist attack is planned on American soil during the coming the Fourth of July holiday weekend, perhaps the most highly symbolic day in the American calendar outside Sept. 11 itself.

“At this point, the intelligence does not warrant us going to a higher alert level,” says Rachael Sunbarger, chief spokesperson for the department. “Certainly it’s not uncommon for there to be discussions of symbolic targets, and our holiday weekend,” in the voluminous “chatter” that intelligence analysts sift through daily. “But so far, there has been no discussion here [at the Department of Homeland Security] that we should go to orange.”

Indeed, Sunbarger’s boss, Homeland Security Secretary Tom Ridge, specifically has expressed concern about the number of times the threat level has been raised to date. “We worry about the credibility of the system,” he told reporters earlier this month. “We want to continue to refine it because we realize it has caused some anxiety.”

Three times already this year, in early February, then again just before the Iraq war, and finally during the Memorial Day holiday in May, the nation has gone to “orange” alert.

Since Ridge’s comments, his department announced a review of the system aimed at allowing the government to warn specific regions of the country of a heightened risk without causing the entire American law enforcement community to ramp up. The Bush administration has said it hopes to have a refined alert system in place by next summer.

This has been greeted warmly by interests who have begun to chafe against what they see as politically motivated decisions to raise the alert status to protect the administration from later accusations of laxity should an incident occur. Among these interests: state and local officials whose budgets take a hit each time the alert status is raised; law enforcement agencies and other first responders feeling the stress of overtime hours; and large corporations who fear exposure to lawsuits if they don’t react sufficiently.

“Elected officials, and even appointed officials, they understand that if something goes wrong, the worst accusation that they can face is that they withheld information or didn’t react to information they had in their hands,” says a former governor whose state was directly affected by the Sept. 11 attacks. “It is a terrible position to be in, and local officials who complain about the costs of tightening security do so without having to face the responsibility or the consequences of being wrong.”

But officials with knowledge of the discussion inside the Justice Department and in the White House say that there is a spirited debate on the need to go to “orange,” defined as a “high risk” of terrorist attack, one level away from the top “severe risk” level.

“The pattern of America’s enemies is that they strike symbolic targets,” says one federal law enforcement official, requesting anonymity. “The Fourth of July is about as symbolic as they come. Maybe the system isn’t perfect now, but it’s what we have and to pretend that our national holiday wouldn’t be an enormous propaganda target for al-Qaida is dishonest.”

Adding to the argument of those who would like to see the level raised again are intelligence reports revealed in last week’s editions of Newsweek that describe an alleged plot to attack oil facilities in Texas. Homeland security officials have not commented publicly on those reports, but officials told MSNBC.com this week that warnings were issued to oil companies and state officials in the president’s home state.

But is that intelligence report enough to trigger a nationwide alert? The dilemma facing those who make these decisions is as old as government itself.

Back in the 1920s, for instance, a U.S. Army general named Billy Mitchell was court-martialed for stating publicly that, someday, the Japanese Empire might strike a lethal blow at the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor using air power. During his cross-examination, the Army’s prosecutor asked Mitchell if he realized he risked panicking the American people. His answer: “I’d rather have the people scared then dead.”

The debate between those concerned about “panic” and those who fear “crying wolf” continues today, not only over terrorism, but also in the way the government handled information about outbreaks of the SARS virus.

Larry Johnson, a former CIA official, says the constant ups and downs of the terrorism alert system probably do reflect real security concerns. But, he says, the pattern so far “has led people to think that the government is crying wolf.”

“When warnings are issued and nothing happens, people become complacent,” he says. “They start discounting them, thinking the government’s not telling them the truth, or that they’re exaggerating the threat.”

Don Hamilton of the Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism in Oklahoma City and a former State Department counter-terrorism official, says “the crying wolf problem is severe and permanent.”

Sunshine or darkness?

But Hamilton also warns that officials sometimes use the fear of “panic” to avoid tough decisions.

“The impulse to say, ‘We don’t want to start a panic here’ gives officials a noble sounding excuse to play for time,” he says. There may be good reasons to do so, Hamilton says, but he says the reality of modern journalism is that if officials leave an information vacuum, they need to try and fill it as accurately and quickly as possible.

“People who have not been journalists or close to journalists do not understand that the evening news goes on the air whether the source has all the facts or not,” he says.

The political calculus that goes into such decisions is widely condemned. But no one seems to have a solution.

“In this day and age, if you provide them with too much general information that does nothing more than increase anxiety, I don’t think that that’s useful,” says Gerard Leone, the federal prosecutor in Boston who handled shoe bomber Richard Reid’s case.

“For us to even hint that the public bears some kind of responsibility for rooting out these people is an abdication of what we in law enforcement do for a living,” says Leone. “The public should go on doing what it does, have trust in its law enforcement officials, and realize that inevitably no nation can stop every evil act directed at it. It’s just not possible.”