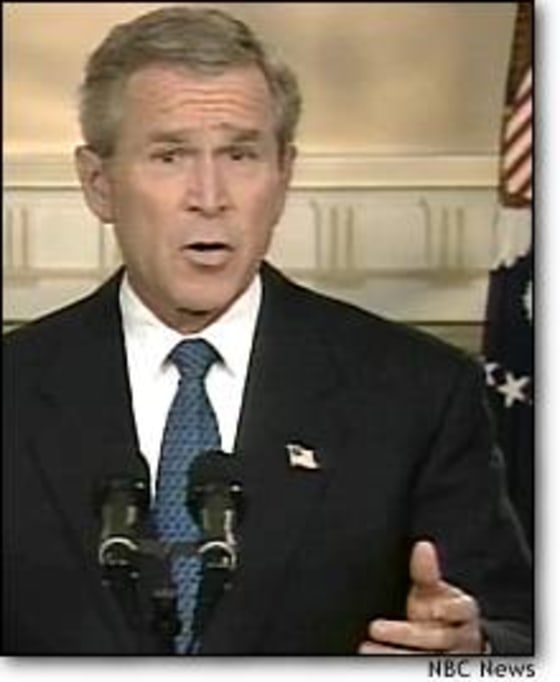

An extraordinary reversal of political fortune compelled President Bush to go on national television Sunday night. He had no triumphal news to announce. Instead he had to brace the American people for an unexpectedly difficult struggle in the months ahead in Iraq, assuring them that the goal — a stable country that is not a haven for terrorists or a site for making nuclear, biological or chemical weapons — was worth the lives of the soldiers and Marines that are being lost.

Bush's speech came at a time when Democrats have grown more hopeful that the open-ended risks of the Iraq commitment will alienate voters from Bush and sweep a Democrat into the White House next year.

It was inevitable that the sky-high poll numbers that Bush enjoyed immediately after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks would settle to more typical levels, but the decline in Bush’s approval rating has been more marked as the U.S. casualties have mounted in the past few months.

2004 REFERENDUM ON IRAQ

Now the 2004 election — little more than a year away — is shaping up as a referendum on Bush’s doctrine of pre-emptive war, the argument that he made in the year leading up to the invasion of Iraq that it would be too dangerous for the United States to wait until Saddam Hussein’s regime had developed weapons of mass destruction.

It will also be a referendum on America’s uncomfortable role as custodian of Iraq, a country whose citizens seem increasingly ungrateful for having been liberated from Saddam’s tyranny.

To make his case, Bush appealed Sunday night directly to Americans’ self-interest or, rather, to their instinct for self-preservation.

“The surest way to avoid attacks on our own people is to engage the enemy where he lives and plans,” he declared, putting the enemy who struck America on Sept. 11, 2001, in the same category as those who are attacking U.S. soldiers in Iraq. “We are fighting that enemy in Iraq and Afghanistan today, so that we do not meet him again on our own streets, in our own cities.”

There was one question Bush did not answer or even try to: When will the occupation of Iraq end?

The president offered no talk of “a light at the end of the tunnel,” only a pledge that “for America, there will be no going back to the era before September the 11th, 2001 — to false comfort in a dangerous world. We have learned that terrorist attacks are not caused by the use of strength — they are invited by the perception of weakness.”

The prism of Sept. 11 remains the key to understanding Bush’s policy. He believes he is deterring future attacks, not inviting more of them, by pursuing the occupation.

CAN DEMOCRATS GAIN?

The electoral question for Democrats is: How can their presidential candidate profit from Bush’s agony in Iraq?

Assuming the U.S. economy does not slide into recession, the core questions facing voters next November will likely be: In whom do you place more trust to conclude the Iraq occupation on something like successful terms?

Will the majority of voters decide that a Democratic president such as Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut or former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean could do better — or at least no worse — than Bush is doing?

Will the situation in Iraq have deteriorated by November 2004 to the point where the Democratic candidate can simply say “it’s a mess” and win the election?

“In order for it to be a successful speech, the American people are going to ... have to see a recognition that the policy we have in Iraq has been a failed policy,” Democratic Sen. Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts said Sunday before Bush spoke.

But what should replace that “failed policy”?

That is the question the nine Democratic contenders will answer in the coming weeks.

LIEBERMAN: MORE U.S. TROOPS

For his part, Lieberman said Thursday at a Democratic debate in New Mexico that he would send more U.S. troops to Iraq “because the troops that are there need that protection.”

Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass., vehemently disagreed, saying that sending more troops “would be the worst thing. We do not want to have more Americanization; we do not want a greater sense of American occupation.”

Kerry urged Bush to “do everything possible” to persuade other countries to share the burden of policing Iraq.

And Dean said more troops are needed but, “They’re going to be foreign troops, as they should have been in the first place, not American troops. Ours need to come home.”

In a statement issued immediately after Bush spoke Sunday night, Dean suggested that rather than making Americans safer by the invasion of Iraq, Bush may have made them less safe.

“How are we actually safer for having gone to war?” he asked. “We were told that Saddam Hussein had an incipient nuclear weapons capability and large stocks of chemical and biological weapons. Where are they? Have terrorists gotten their hands on them because we failed to secure them, or were they never there? Before the war there was no evidence of any link between Iraq and al-Qaida. Now al-Qaida sympathizers and organizers are streaming to Iraq in ever greater numbers, feeding off of the resentment of the Iraqis and targeting our servicemen and women.”

The assumption among all the Democratic contenders is that NATO countries and nations such as Morocco would be willing to chip in troops — if only a president other than Bush would ask them.

Although none of the Democrat contenders has yet acknowledged the fact — nor, for that matter, has Bush — the 2004 election will be the first wartime election since 1972, when U.S. forces were still fighting in Vietnam.

The Democratic candidate will be at something of a disadvantage because Bush can control the timing of events, such as strikes on terrorist havens or announcements of the capture of key terrorist leaders.

Democrats harbor deep distrust of what they see as Bush’s manipulation of the terrorism issue. Jim Jordan, ex-director of the Democrats’ Senate campaign committee and now Kerry’s campaign aide, said in September 2002, “It’s absolutely clear that the administration has timed the Iraq public relations campaign to influence the midterm elections . . . and to distract the voting public from a failing economy and an unpopular Republican domestic agenda.”

Six weeks later the Republicans swept back into control of the Senate and added to their House majority.

But as commander-in-chief, Bush will not always be the master of events — sometimes he’ll be at their mercy. He may again feel compelled to come to the American people and argue that their own survival is at stake in Iraq.