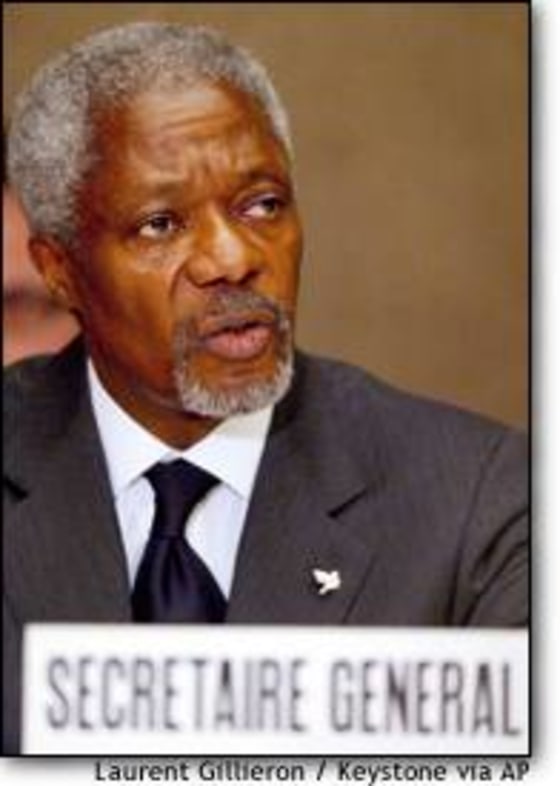

U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan, scrambling to heal a traumatized world body, says a U.N. role in Iraq would grant “legitimacy” to the postwar administration. But as the deeply divided Security Council squabbles anew over lifting prewar resolutions that sought to disarm Saddam Hussein peacefully, the United States is fast-tracking its reconstruction plans, organizing meetings of political leaders, establishing ministries, supervising the inflow of humanitarian aid and enforcing security — in short, all the things the United Nations had hoped to be doing.

The message from the Bush administration, and especially the top brass in the Pentagon, is clear: The United States — with the help of its coalition partners — won the war. Now it will establish the peace on its own terms.

By the end of May, the United States wants what it views as outdated U.N. sanctions lifted and a U.N.-administered system for selling Iraqi oil wound down to allow the sale of the nation’s most valuable resource to fund reconstruction.

Furthermore, Washington has ruled out any role in the foreseeable future for U.N. weapons inspectors — to the chagrin of many of its opponents on the Security Council — even as Saddam’s alleged weapons of mass destruction remain elusive.

All in all, the conditions leave little room for the United Nations, except for humanitarian organizations such as UNICEF and the World Food Program, which are already active inside Iraq.

On the run?

“The United States has the United Nations on the run,” one U.S. diplomat said, speaking on condition of anonymity. “It turned the tables on France, Russia and others,” he said, referring to the war, which followed a bitter debate over a resolution in support of military action. “They are now rushing to catch up.”

France and Russia, veto-wielding members of the Security Council, led the charge to avert military action to oust Saddam — foiling U.S. hopes for a resolution to authorize war and drawing the scorn of the Bush administration.

France, in particular, has been put on notice that President Jacques Chirac’s outspoken opposition — and the globe-trotting anti-American lobbying by Foreign Minister Dominique de Villepin — will not go unpunished.

“I doubt he’ll be coming to the ranch any time soon,” President Bush told NBC last week, referring to Chirac, who recently broke the ice with a 20-minute telephone conversation with Bush, which was described by the White House as “businesslike.”

Bush also hinted at Washington’s deeper suspicions about France’s strategy.

“Hopefully, the past tensions will subside and the French won’t be using their position within Europe to create alliances against the United States, or Britain or Spain or any of the new countries that are the new democracies in Europe.”

New resolution

According to one proposal circulating within the administration, Washington wants an interim Iraq government, with responsibility for oil sales, up and running by June. The plan would offer the sop of a consultative role to a U.N. representative chosen by Annan.

In reality, the plan — which would require a fresh resolution — would further sideline the United Nations by unhitching the Security Council from its role as administrator of Iraq’s oil sales.

Washington is squaring for another tough fight on the Security Council to win endorsement for the plan, using its considerable muscle as the de facto power on the ground.

“The U.S. is going to get most of what it wants,” one U.N. official predicted. “They won the war; who is going to stand in their way in the Security Council?”

A spokesman for Annan said he will take his guidance from the council, although the secretary general would like to find a way to rebuild the unity of the council following the divisive prewar debate.

Overall, the secretary-general feels “there would be greater legitimacy in the eyes of the Iraqi people and of Iraq’s neighbors if there was some sort of U.N. involvement in the political process in terms of finding a new leadership for the Iraqi people,” the spokesman said.

Blair's credits

Annan’s strongest ally may be Britain, which has socked away a trove of credits with the Bush administration.

Prime Minister Tony Blair is riding high after his alliance with Bush — at the expense of European unity and domestic support — was rewarded by a swift victory with minimal casualties.

But the British leader would like to mend relations with his European partners, especially France and Germany, to fortify the European Union. And he wants to salve the still-raw wounds after a rancorous debate in his own Labor Party by recommitting himself to the United Nations.

With that in mind, Blair has proposed a “vital” role for the United Nations in Iraq.

A British official said this should include a political role. “It is going to be important that any new Iraq authority is credible locally and internationally, and we think that the United Nations could play a part in that,” the official said.

The British envision the United Nations playing a role similar to the one it played in Afghanistan, where the post-Taliban government was organized under U.N. auspices at a conference in Bonn, Germany.

British officials downplay any rift with Washington on the subject, insisting the United States has yet to present its final plan.

Meanwhile, the postmortems continue in the French and Russian capitals, the clear losers in the international showdown.

By staking their claim to the antiwar mantle, the two nations risked forfeiting a say in the aftermath, any contracts from the reconstruction bonanza as well as a favorable disposition of their outstanding debt claims against the previous regime.

According to one study, Russia alone is owed $12 billion, mostly from arms sales.

“The Russians want somehow to make the Americans forget about their opposition during the prewar period,” said Victor Kremenyuk, a political scientist at the Institute of USA and Canada Studies in Moscow.

“They feel they overstated their opposition. And it has not played a positive role; it ended with something like Russian humiliation. So it would be better if now just the both sides could start from a clean page.”

For France, the alliance with Russia was formed by mutual convenience rather than a deep-rooted bond between Chirac and President Vladimir Putin. And the French worry Moscow will quickly abandon the antiwar axis to curry favor with Bush.

At home, Chirac’s image as an untrustworthy politician was washed away with his antiwar rallying calls. But he’s unlikely to maintain his hostile approach to Washington.

“A face-saving compromise will have to develop,” said Simon Serfaty, the director of the Europe Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “The French, Germans and Russians may insist on some kind of formula to say they didn’t just give in under pressure.”

Compromise

A compromise may in the long run also appeal to the United States. Even though some of Bush’s more hard-core supporters might savor the chance to further diminish the United Nations’ status, analysts and diplomats say the task in Iraq may be too much for the United States to go it alone.

Some estimates reckon the United States may have to remain in Iraq for at least two years and that the final tally for war and reconstruction could top $100 billion.

“It would lighten [the American] load in the sense that other governments and international organizations will be more inclined to help on the ground,” said Eric Schwartz, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a former National Security Council aide.

Schwartz was project director for a CFR task force report entitled “Iraq: The Day After.”

Among the recommendations were that the United Nations should endorse U.S. leadership in Iraq but also “authorize meaningful international participation — and shared decision-making — on humanitarian assistance, a new Iraqi constitution, the U.N.-supervised oil-for-food program, and reconstruction.”

Schwartz said that rebuilding Iraq is a long-term project that would be helped by a broad international involvement in such areas as financing for development and support and training for a civilian police force.

David Malone, the head of the International Peace Academy and a former Canadian ambassador to the United Nations, noted Iraqis themselves are not enthusiastic about the coalition forces and may welcome international assistance.

“And while it would be irresponsible for the U.S. and Britain to leave right away, I do think that an international presence, which would help to developing a long-term Iraqi government, would be helpful for the Iraqis and also for Washington and London.”

Moreover, the British official said, widening the participation in postwar Iraq would allow the coalition to confront suspicions in Iraq and elsewhere that their only motivation was to exploit the oil reserves.

But the details need to be hammered out. “The question of control is the most difficult,” the official added.

NBC’s Linda Fasulo at the United Nations, Judy Augsburger in Moscow and Jennifer Carlile in London contributed to this report.