More than 8,000 students were evacuated from schools near the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, and scenes of parents rushing through the chaos to retrieve their children shook up moms and dads everywhere. But the attack spawned few specific changes in school safety procedures, which had only recently been overhauled after a wave of fatal school shootings. Now, as the nation ponders the threat of new attacks, parents and educators wonder if measures designed to prevent another Columbine massacre are really enough in an age of terror.

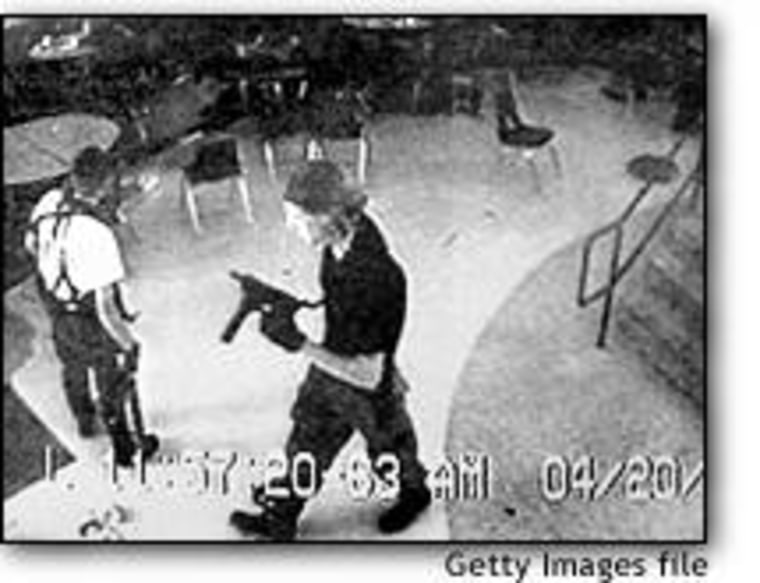

The Columbine High School shootings in Littleton, Colo., in which two students shot and killed 12 of their peers and one teacher before taking their own lives on April 20, 1999, were the deadliest of their kind in the United States. The rampage redefined standard safety procedures, leading even relatively trouble-free schools to restrict access to their premises, more closely monitor staff and students, and devise plans to manage an array of potential crises.

At Washington Elementary School in Janesville, Wis., measures put in place before hijackers turned four jets into suicide missiles last September included “locking all doors except front and rear, installing video cameras on doors, implementing ‘lock-down’ drills, requiring all staff to wear picture ID’s,” said Principal Rick Mason.

Safety procedures at schools “really worked on Sept. 11, and [they] worked because of Columbine,” said June Million of the National Association of Elementary School Principals.

Because of post-Columbine safety measures, principals across the country say their emergency plans only needed minor adjustments after Sept. 11.

But some experts believe the magnitude of the terrorist attacks calls for broader, more centralized measures.

“Even the corrections made after Columbine would not necessarily work in the case of another terrorist attack,” said John See of the American Federation of Teachers.

Some wonder what would happen if future terrorism was deliberately aimed at schoolchildren.

“We need to be prepared for wider-scale events, or things like food contamination,” said Curtis Lavarello, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers, a non-profit organization that trains law enforcement officers to work in schools. “What if all our schools are affected at the same time?”

But, as See noted, “this is a country where there is no centralized school system. The federal government represents 10 percent of a school’s funding, so it probably has around that much influence on safety procedures.”

Because of this, educational professionals say coordination among parents groups, school administrators, teachers, school boards and state legislatures is crucial.

In a letter sent Feb. 14 and titled “Lessons Learned and Recommendations,” the federal Department of Education urged principals to collaborate closely with local law enforcement, fire officials and emergency services to make sure their schools are included in community-wide emergency drills.

Some educators fear that complacency and an unwillingness to even contemplate something as horrible as an attack on a school may leave schools vulnerable.

“There are far too many schools that just don’t believe that a crisis will affect them,” said Lavarello.

Even at schools near the World Trade Center site, the idea that children could be directly targeted remains remote. “We were not a target on Sept. 11, so let’s not be overanxious,” said Beth Schiffer, the mother of two at New York City public school No. 234, located two blocks from Ground Zero.

Ken Trump, the author of two books on school safety and the executive director of National School Safety and Security Services, a Cleveland-based consulting firm, says that attitude is dangerous. “We only need to look to the Middle East and Ireland to know that schools and school buses loaded with children have been targets for terrorists,” he said.

Finding the right balance

Some principals argue that it’s impossible to be fully prepared for any attack or disaster.

“Given a terrorist attack, that’s beyond our control,” said Lorraine Lotowycz, principal of Hamilton Elementary School in Bridgewater, N.J. “Children with weapons in our building, that’s within our control.”

And although Sept. 11 did not lead to a new wave of specific security measures, it would be wrong to minimize its impact on school safety.

“Saying that Sept. 11 has not brought dramatic changes in school safety depends on how you define ‘dramatic,’ ” said Lotowycz. “It has refocused us again, and that in itself is dramatic.”

Lotowycz, whose school is near a major shopping mall, has increased collaboration with local police, ordered two “crisis bags” containing first-aid and emergency aid material, and had 14 staff members train in cardio pulmonary resuscitation.

“It’s a matter of being on heightened alert, and we are,” she said.

Parents also need to be more vigilant, educators say. “The laws are in place, the plans are in place,” said Kay Trotter, vice president of Community Concerns with the California Parent-Teacher Association. “Every parent must, or should, go to their school and ask for a copy of the school’s on-site emergency plan.”

The challenge, educators say, is to balance safety with comfort.

“On Sept. 11, part of our children’s childhood was stolen,” said Lotowycz. “We have to find a balance because these children are entitled to a childhood as well as to a safe environment.”