They can see through your clothes and tell exactly who you are just by glancing in your eyes. Some can even smell you. Since Sept. 11, a new breed of high-tech security devices has been rushed to market, and they could be coming soon to an airport near you. But the various new technologies are sure to run into turbulence along the way, as the flying public decides just how much it’s willing to pay — literally and figuratively — to feel safe again.

In an attempt to help screeners stop potential terrorists in their tracks, the U.S. government and a handful of airports across the country are testing new contraptions and biometrics systems reminiscent of “The Jetsons” that can identify passengers by unique physical traits like a fingerprint or an iris pattern.

Much to the chagrin of civil libertarians, it no longer seems a question of whether new cutting-edge equipment will be deployed, but when.

With $50 million a year earmarked for the development of advanced technology, the Transportation Security Agency, or TSA, the month-old federal agency now in charge of all the nation’s airport checkpoints, is shopping around.

“Congress is opening its checkbook,” says Tom Jensen, president and CEO of the National Safe Skies Alliance, a nonprofit group that tests new aviation security devices and prototypes. “But one of our main concerns is that they don’t spend the money on stuff that doesn’t work.”

To avoid bad choices by lawmakers eager to allay the public’s current fear of flying, the TSA has asked Safe Skies for help. Now, at Orlando International Airport in Florida, passengers can volunteer to go through security procedures designed to test a series of new devices the government might consider investing in.

‘Virtual strip search'

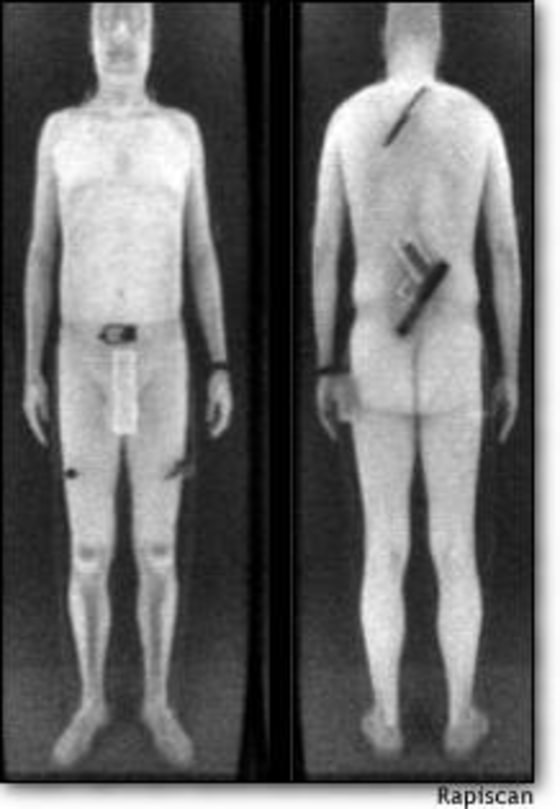

One of the most controversial items is Rapiscan’s Secure 1000 body scanner, a low-energy X-ray that goes beyond today’s metal detectors by beaming through a passenger’s clothes to reveal the outline of foreign objects next to their skin. It can detect metal, as well as anything inorganic — from a polymer gun to plastic explosives.

But it also sees other shapes, including the general outline of the body and genitalia.

“This, of course, is a virtual strip-search,” says ACLU associate director Barry Steinhardt. “There’s no question this has tremendous potential for embarrassment.”

But the machine’s makers, as well as those who have tested the Secure 1000 independently, say the strip-search comparison has been overblown. According to Jenson, the X-ray’s images of people’s more private parts are blurry at best. Plus, the screeners, who are male for men and female for women, sit behind a wall and don’t even see the passenger they’re viewing in person unless they detect something suspicious. Finally, only certain passengers — chosen either at random, or because something about their demeanor or appearance concerns a screener — would be asked to have the scan in the first place.

“Knowing what I know about it,” says Jenson, “I’d say ‘X-ray me and let me go on my way.’ With the ACLU, it’s always react first and then find out what it does later.”

Hands off

Bryan Allman, the project manager for Rapiscan’s body scanner, says some travelers may prefer the machine over current inspection methods. “I fly like everyone else,” he says. “And I don’t enjoy being hand frisked at airports. This is much less intrusive in my opinion, because nobody touches you.”

The machines emit radiation, but the levels are so low that there are said to be no medical concerns.

The federal Immigration and Naturalization Service already uses body scanners, but given the sensitive nature of what they can “see,” their widespread use could still be a few years away, experts say.

Another device being tested, the phone booth-sized Barringer Ionscan 400, blows jets of air at passengers. Because heat rises, microscopic particles float into overhead sensors, which then “sniff” the air to detect any trace of explosives. As an added bonus for law enforcement officials, the Ionscan also can be adjusted to test for 60 types of drug residue, which worries civil liberties advocates like Steinhardt, who says, “Do we really want to turn airport security personnel into the DEA?”

Even the less controversial devices being considered by the government would give screeners a real leg up, experts say. A bottle scanner in the Orlando experiment, for example, can determine what kind of substance is in a sealed container.

And a dual-image X-ray looks at bags from two directions simultaneously. “In one dimension, a knife just looks like a line,” says Jenson, “but another view would show the flat side of the blade, making screeners’ jobs much quicker and easier.”

Biometrics is key

Aviation insiders agree, however, that deploying all of these high-tech gadgets together would be too expensive, clunky and time consuming — unless they were combined with biometrics ID cards that would identify pre-screened passengers.

“You need to take the low-risk people and get them through the system quickly, so you can focus your efforts on the higher-risk people,” says the Progressive Policy Institute’s Robert Atkinson, a leading proponent of what’s become known as the “trusted traveler” card.

Proposed as a voluntary system, fliers would be granted a card only after an initial background check using computers linked to FBI and INS databases. Then, at airline check-in gates, they’d be asked a la “Star Trek” to put a finger on a scanner, or look into an eyepiece to prove they were indeed the person they claimed they were. So-called “trusted travelers” would go through the standard security checks, but they would not be subjected to time-consuming random searches and additional screening machines.

Identifying 'bad actors'

Advocates say the background check would be much like a routine credit report, and might examine things like a passenger’s residential and flying history.

In Israel, often held up as the gold standard for airport security, a biometric program for passengers already exists. Over the past three years, 85,000 Israelis have signed up for the EDS Express Entry system, which allows them to speed through security and immigration at special electronic kiosks where they simply insert their cards and put their hands on a special reader.

“Biometrics has reduced plane-to-curb time at Ben Gurion from about two hours per passenger to 15 minutes,” says Bret Kidd, a vice president at Electronic Data Systems, which manages Express Entry. “Physical security should always be there, of course, but you also need to identify the bad actors, and biometrics helps expedite the process for those who opt in.”

Kidd believes that systems like EDS Express Entry, the latest version of which was unveiled at the most recent COMDEX technology conference in Chicago, will ultimately be used in the United States.

“The thought until now was that if we’re going to increase security, we’ll have to decrease convenience and efficiency,” says Kidd. “What we’re saying is that with biometrics, that’s simply not the case.”

Avoiding another 9/11

The ACLU has consistently opposed the idea of biometric cards — even if they are voluntary — because of privacy concerns and fears that they might be granted unfairly based on racial profiling.

But Atkinson, who wrote the congressional policy paper “How Technology Can Help Make Air Travel Safe Again,” insists that integrating biometrics at all levels of airport security may be the only way to prevent more attacks like the ones on Sept. 11.

“Four out of the five hijackers on the Dulles flight were on phony driver’s licenses,” says Atkinson. “So, when we’re talking about people driving planes into buildings, ‘fairness’ and ‘privacy’ shouldn’t be the ultimate criteria.”

MSNBC.com’s Ursula Owre Masterson is based in New York.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.