The United States is pouring $1.3 billion into Colombia to support the same carrot-and-stick strategy that has failed over the past decade to stem the steady flow of cocaine and heroin from this South American nation to the world’s hungriest drug market. The difference now is that the stick is bigger and the stakes are higher.

The main goal of Plan Colombia, as the latest initiative is known, is to slash the current 300,000 acres of coca fields by half in five years using both forceful eradication and alternative development programs for farmers who harvest the illegal crop.

Success on that front is key to the government’s strategy to wrestle the nation’s most powerful insurgent army into signing a peace deal to end its nearly 40-year war against the state, funded in large part through the drug trade.

By undercutting the rebels’ main source of income, the government hopes to cripple the insurgent army and see peace talks bear fruit.

Failure of the policy could mean all-out war. Indeed, while the government’s military offensive has begun near rebel strongholds in southern Colombia, intelligence reports indicate the rebels may already have surface-to-air missiles that could down helicopters and crop-spraying planes.

Past failure, future hopes

Given the steady world demand for cocaine and the astronomical profits to be made from the trade, drug policy experts say the plan to eradicate drug production will likely only shift cultivation deeper into the Amazon basin and possibly to neighboring countries.

Despite the aerial spraying of 300,000 acres of coca crops since 1994, and multi-ton seizures of powder cocaine, Colombia remains the largest single source of the drug to the United States, feeding 90 percent of America’s $36 billion-a-year cocaine habit.

And as the U.S. cocaine market levels off, nimble Colombian drug traffickers have moved in on the $12 billion annual heroin trade.

Colombia has been fighting drugs since the first commercial marijuana crops were detected in the late 1970s. In the 1980s, the nation’s drug traffickers turned on to the cocaine market, with the notorious Medellin and Cali cartels establishing vast, multinational networks stretching from the coca fields in Bolivia and Peru to processing centers in Colombia, and distribution networks in the United States.

Cartels crushed, but trade flourishes

Even after the cartels were crushed in the mid-1990s, the drug trade continued to boom under the auspices of dozens of low-profile organizations.

Colombia’s anti-narcotics police chief, Gen. Gustavo Socha declined to speculate about how many drug-trafficking organizations run the business today, but independent estimates run as high as 100.“They are all independent traffickers and no one knows who they are,” said a U.S. official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

The heirs to the big cartels now run the business with partners that include right-wing paramilitary groups and leftist rebels. The deadly alliances have brought Colombia to a crossroads where the double curses of drugs and political conflict have become intricately intertwined.

That shifting nature of the narcotics trade has moved the focus of the drug war from Colombia’s largest cities to the countryside, and from police control into the hands of the military.

The offensive begins

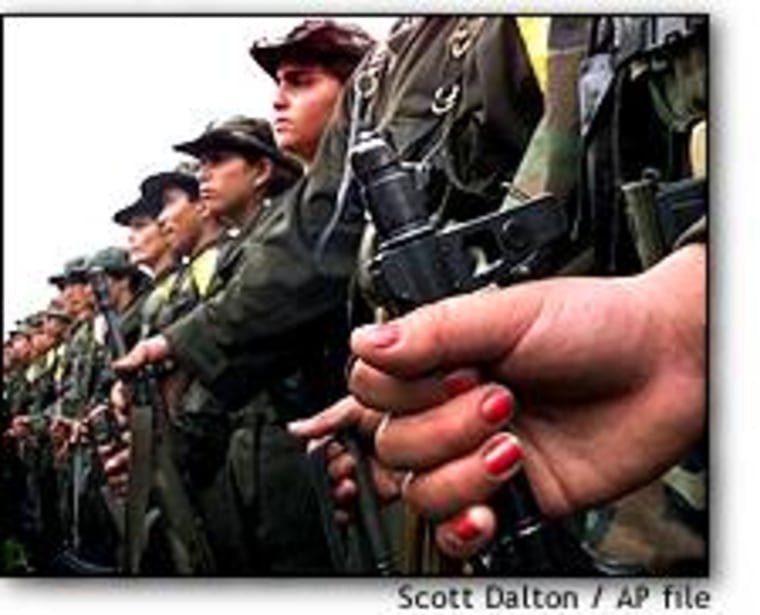

U.S. and Colombian officials say the 17,000-strong Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia are a main player in the trade in southern Putumayo province, where nearly half of all Colombian coca is grown. In recent years, the rebels have kept eradication efforts there virtually in check by firing on crop-spraying planes and whipping peasants into frenzied protests against the spraying policy.

“The presence of irregular forces makes any action by the state more difficult,” said Gabriel Merchán, who is in charge of government anti-narcotics policy.

Plan Colombia aims to turn the tables. In the first strike of the initiative, two counter-narcotics battalions trained by the U.S. Special Forces escorted crop-spraying planes on daily sorties for more than six weeks, overseeing the destruction of more than 72,000 acres of coca crops in Putumayo province. Ground forces then stormed the browning fields and destroyed more than 20 rustic labs where leaves are turned to coca paste.

Farmers ponder options

Santos Bastillas, 36, was one of the first farmers hit by the strike, which began in December.

His seven-acre farm near the town of La Hormiga was sprayed Dec. 22, destroying his entire coca crop and a few fields planted with food as well.

He says he’s not sure now what will happen to him, his wife, and four children. When aerial spraying began seven years ago in southeastern Guaviare province where he worked as a “raspachin,” or coca harvester, he came to Putumayo. Now, he could decide to move deeper into the jungle to grow coca, or he could sign on to a government-sponsored crop-substitution program.

Past programs have failed to wean farmers from coca, partly because of unfulfilled government promises of help to switch to legal crops. This time around, however, the promises come backed by $58 million in U.S. aid.

But Bastillas is not convinced. “Who knows what this land will be good for now,” he says, wondering about the effects of the weed-killer glyphosate, which was sprayed on his land. Conservationists say soil sprayed with the defoliant could be barren for years, while the government says the land can be planted again in a few months.

While Bastillas ponders his future, Gen. Mario Montoya can hardly contain his glee. Montoya is commander of Colombia’s Southern Joint Task Force, which includes the two U.S.-trained counter-narcotics battalions, as well as police, air force and navy units.

“This was our dream and it is becoming reality,” he said.

Rebel financing

Even before the military began making its move in Putumayo, the rebels had been fighting right-wing paramilitary groups over control of the coca.

The rebels have controlled the rural areas of Putumayo for years, financing their insurgency through taxing farmers and the drug traffickers who buy the coca paste.

But after the paramilitaries gained control of several towns in Putumayo in 1998, the rebels changed their tack, obligating farmers to sell their paste production to the rebels, who resell it — at a significant mark-up — to independent drug-running organizations. Colombians call that link in the drug chain a “cachipato.”

This allows the rebels to exclude from the drug market people with links to their right-wing enemies, who also depend on drug proceeds to finance their paramilitary operations. Perhaps as importantly, the rebels’ control of the drug trade has allowed them to escalate their war against the government.

The government estimates that the intermediation fees account for 70 percent the rebels’ multimillion-dollar war chest.

Rebels claim limited role

Although farmers and local officials in Putumayo confirm rebel orders to sell only to the guerrillas, the rebel leadership denies it is buying the paste, insisting that it only taxes the drug trade.

Rebel spokesman Carlos Antonio Losada refused to comment further. “I do not speak to U.S. media on that subject,” he said in San Vicente del Caguán, the capital of a rebel safe haven set aside for peace talks with the government.

Smiling snidely, he added: “Statements aren’t going to stop Plan Colombia,” which the rebels see as a flimsy excuse for direct U.S. intervention in Colombia’s internal conflict.

Drug policy expert Ricardo Vargas said recent statements by U.S. officials characterizing the guerrilla group as a drug cartel misrepresent the rebels’ role. “They see the guerrillas as one of many drug trafficking organizations, and the most important one at that,” he said. “The day the FARC begins to export and controls the arrival (of the drugs) in consumer markets — then it’ll be just another drug syndicate.”

Fighting a scourge

The United States says it has some indications that the rebels already are involved in that stage of the game. Former drug czar Barry McCaffrey said in November that the U.S. Navy had found a guerrilla armband and pamphlets on a speedboat transporting two tons of cocaine to Mexico. And a Colombian physician captured in Mexico is suspected of negotiating with distribution cartels in that country in the name of the rebels.

“Every day it is getting harder for the guerrillas to maintain the illusion that they are not involved in drug trafficking,” Merchán said.

But anti-narcotics chief Socha said he doesn’t care whether the traffickers are guerrillas or not. “I don’t care whether it’s Pedro or Juan or Cain or Abel. We detect illegal crops and we will fumigate illegal crops, without finding out first whose it is,” he said.

“We will hit whoever we have to to fight this scourge.”