Christine Kowi had a good life. As a secretary, she earned $700 a month in a country where the average income is $300 a year. Her husband, Walter, was a successful technician. Their three children all went to private school, and the family lived in a posh neighborhood. Then, in early 1996, her life changed. After a routine medical check-up at her office, she was fired. “I never suspected HIV,” Christine said. “I thought it was a disease for poor people. I just thought the company needed a new secretary.”

Soon after, Kowi got into a serious car accident. A blood test at the hospital confirmed that she was HIV positive.

In Africa, traditions, economics and ignorance conspire against the fight to stem the spread of HIV and AIDS. Kowi found out quickly that not only her life, but her way of life, was going to change.

Her husband came to see her at the hospital. “He told me not to come home,” she said. “He said he would be too embarrassed.” Walter then instructed the doctors not to call any of his family members if his wife died.

Meanwhile, her father disappeared from the family home in Kisumu, in western Kenya. His parting note read: “Don’t look for me. Our only daughter, who is taking care of us, is already dead. I am never coming back home.”

Convinced that his wife somehow contracted HIV in the car crash, Walter Kowi refused to be tested. Instead, he re-married, without telling his new wife he might be a carrier. Four months later, he contracted pneumonia and died. His new wife followed a few months later.

A difficult road

Although recovering from the accident, Christine Kowi contemplated suicide. “AIDS was going to kill me anyway,” she said. That’s when she was introduced to The Association of People With AIDS in Kenya, or TAPWAK. There, she met people from all walks of life.

“I was surprised to see even doctors who were HIV positive,” she said. “This empowered me. I realized it was not the end. And I wanted to tell others the same thing.”

AIDS counseling is a tough job anywhere. But in Africa, where the subject is taboo, it is particularly daunting.

“People hear ‘ukimwi’ (the Swahili word for AIDS) and all they know is that you’re facing the grave,” said Kowi. When prominent Africans perish from AIDS, their deaths are often attributed to “short illnesses.” It is, says UNICEF chief Carol Bellamy, a “conspiracy of silence.”

The numbers are staggering: More than 22 million people are infected with AIDS or HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. About 11 million Africans have died from AIDS in the past 15 years, a quarter of a million in Kenya. An estimated 1.5 million Kenyans live with HIV/AIDS.

Facing tragedy

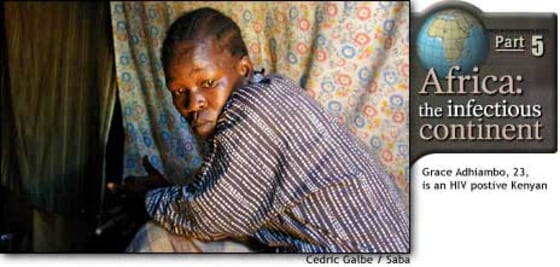

In the abject slums of Maili Saba, on the borders of the sprawling housing estates east of Nairobi, Grace Adhiambo, 23, was cleaning her one-room mud house when Kowi came by for a counseling session.

Adhiambo, a soft-spoken woman with a shy smile, has lived with HIV for 11 years. She contracted it when she was raped as a 12-year-old orphan. The woman for whom Adhiambo worked at the time arranged with the parents of the rapist that he should marry Grace. Paul, her husband, beat her daily and prevented her from getting family planning advice.

After Adhiambo gave birth to three children, at the age of 15, her husband told her he was HIV positive. When she threatened to run off, she recalled, Paul laughed. “You’ve already been infected. You can’t run away from this disease,” he said.

Her husband died from AIDS four years ago. According to the tradition of her Luo tribe, Adhiambo was bequeathed as a wife to one of Paul’s four brothers. Because of her condition, however, none of them wanted to sleep with her. A cousin of Paul’s finally agreed to do it for a payment of $75 and a vat of beer. Soon afterward, she gave birth to her fourth child.

“In Kenya, AIDS and HIV rates are high partly because of our traditions and culture,” said Kowi, reflecting on the challenge of education people about the condition. “We have wife inheritance, people don’t use condoms, they use the same knives for circumcision procedures. Violating the tradition in the Luo culture will incur the ‘chira,’ a curse that may take the form of AIDS.”

Now, Grace lives alone with her children. Her two boys, Eric and Frederic, are HIV positive. Her daughter, Julia, 10, is — so far — HIV negative.

Living with AIDS

Adhiambo says the counseling by Kowi has helped her understand the disease.

“When I get hungry, I get sick,” she said. “I’m mostly concerned with getting money to feed my children.” She earns $1.50 a day when she can find some gardening work. AIDS drugs, costing as much as $1,500 per month, are out of the question for most Kenyans.

Meanwhile, Christine Kowi, now 31, lives in the nearby Maringo slums. The rent is $30 a month, a far cry from the $750 rent that she and her husband paid a few years ago. She gets paid to deliver lectures on how to live with HIV.

Her father, Joseph, returned after Christine found him and counseled him about HIV. And despite her burden, she still supports some 20 family members.

Her health has gone up and down. Once she developed boils all over her body. A year ago, her weight dropped to below 75 pounds after she suffered bronchitis.

But for now she is doing well, convinced that her sense of purpose keeps her healthy. “My husband died out of ignorance,” she said. “I don’t want the rest of the world to make the same mistake.”