In a megacity like Greater Cairo, with a population of more than 14 million people, many things are in short supply, including such basics as housing, clean water and space. In response, Egypt is moving ahead with a plan worthy of the Pharaohs: turning huge tracts of the Sahara Desert into inhabitable land.

There's almost never a seat free on the subway, known as the metro — never on the mixed cars where both men and women manage to crowd together without touching, nor on the “women-only” cars where mothers hang onto their children and women chat with friends. Packs of school students, loud and unruly, crush in and out all day. Chivalry is rare, too. On the metro, only the very old are offered seats. People push on without waiting for others to disembark. In the struggle that is daily life, politeness, once the norm, has become a luxury in Cairo.

President Hosni Mubarak, like his predecessor Anwar Sadat, has recognized the need for long-term solutions. Aiming to reduce the skyrocketing population growth of Cairo in the 1960s and 1970s, Sadat established satellite cities: complete, independent communities 25 to 50 miles from Cairo with job opportunities, schools, hospitals and cheap housing.

So it is written ...

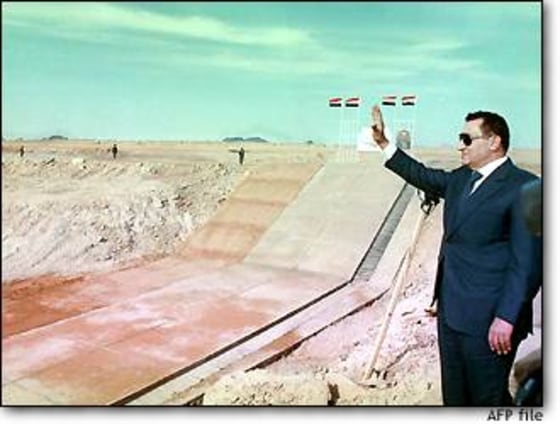

Mubarak followed suit, building many more satellite cities. But Cairo trumped their moves by filling the barren space between with its ever expanding settlements. So, in a desperate effort to expand Egypt beyond the Nile’s shadow once and for all, Mubarak’s engineers are building a new Nile valley in Egypt’s barren southeastern and Western deserts.

The new Egypt tames the desert

The plan calls for water to be siphoned from the overflow of Lake Nasser, the gigantic body of water created by the famous Aswan High Dam. Together with local groundwater, engineers hope to irrigate one million acres of land. The “New Valley,” as it has been dubbed, will increase Egypt’s inhabited area from 4 percent to 25 percent, giving rise to plans for 18 new cities.

A second, only slightly less ambitious project is underway on the Sinai peninsula. There, a “Peace Canal” will eventually channel water from the Nile through Sinai to irrigate 620,000 acres of land for more than 1.5 million new residents. And within a few years, Egypt expects to complete a bridge to span the Suez Canal and link its new Sinai cities with the heartland.

All told, Egypt is spending nearly $4 billion on the reclamation projects, which are due to be completed in the year 2017.

Build it, they will come

Critics of the project argue people won’t move to remote locations homes unless homes there are an improvement over their current dwellings. Plus, the government schemes have to compete with the excitement, culture and job opportunities the big cities of Cairo, Alexandria and Ismailia have to offer.

“They must pay attention to the rural areas by raising the standard of living,” says Dr. Moushira El-Shafei, head of the department of Population and Family Planning.

In the past three years, the government has been trying to do just that Upper Egypt — the impoverished south. Known best to westerners for the splendors of Luxor and other ancient sites, Upper Egypt is also a hotbed of Islamic fundamentalism and a region wracked by terrible poverty. Fearing further migrations to Cairo, the government has been improving infrastructure and services and trying to create new job opportunities in the region.

This is all part of a grander plan by Mubarak’s government to target Egypt’s key problem, an exploding population, now standing at about 64 million. Statistically, at least, the government has met with some success.

Egypt’s family planning campaign has won international acclaim. Although the population is still growing by a staggering one million every 10 months, the pace of growth is decreasing.

From 2.95 percent annual population growth in 1986 the figure fell to 2.1 percent in 1996. Put differently, that means today’s typical Cairo couple are having 2.6 children as compared to 3.8 children ten years ago.

Egypt is aiming for zero population growth by the year 2025. Even at that rate, there will be an estimated 11 million new Egyptians to feed, house and educate and employ by the year 2007.

Cairo suffers

Meeting the needs of this population will be a great test for Egypt — one unlikely to be solved by desert reclamation alone.

In Cairo, for instance, overcrowding touches every aspect of life. Public schools must run three shifts of classes a day, with more than forty students in each class to keep up with Cairo’s growing population.

On the metro, less fortunate children walk barefoot down the aisles selling kleenex, bandages or bobby pins. Without enough jobs to go around, struggling urban families are sometimes forced to send their children to work.

The population explosion also has brought violent crime to a city where once it was relatively rare. Today, murders, violent domestic disputes, rapes and abductions occur every few days. Many sociologists attribute it to the breakdown of the family unit in a teeming urban environment.

With low-cost housing in short supply, slums have sprung up between established suburbs and the city center.

In areas like Mansheat Nasr, a former shantytown which now houses over one million people, there is no running water or electricity. Nor are there basic services in the City of the Dead, a sprawling cemetery where families have made the brick mausoleums their home.

The public buses are so crowded, people actually hang out the door and riders jump on an off as the buses come to a rolling stop. Private minibuses are notoriously dangerous. And driving by car within five miles of the city center involves at least half an hour and one exhaust-choked traffic jam. People drive offensively, relying more on horns than brakes. In the press of cars, fender-benders are frequent. On open roads, accidents are often fatal.

But it’s worse on foot. On the main roads that run along the Nile and up to the Pyramids, most pedestrians have only one way to cross four lanes of speeding, heavy traffic: a perilous stroll to the other side.

Everyone is victim to pollution from the exhaust of thousands of buses, trucks and motorbikes and cars, the belching smokestacks of cement factories and lead smelters in and around Cairo and the practice of burning the city’s garbage in open dumps. Cairo and Mexico City vie for the unfortunate title of most polluted city in the world.

Despite this, lead levels in the air are down by about 75 percent. The government has switched all gasoline to unleaded and is converting bus fleets to natural gas. There are also plans to force lead smelters out of the city and improve filters on cement factory smokestacks.

Even with the crush of new arrivals, the city’s infrastructure has improved since the eighties, thanks to joint government and foreign aid projects. Sewer water no longer floods main streets. Telephones and mobile phones work and water and electricity supplies are reliable in planned communities. New bridges and overpasses help relieve traffic congestion. There are even plans to extend services to places like Mansheat Nasr. So there is hope. After all, in Egypt’s ancient capital, pollution can’t be the only thing that springs eternal.

Charlene Gubash is an NBC News producer based in Cairo.