The McDonald’s on the corner was the first sign that Meng Qinglong’s Beijing neighborhood would never be the same. Meng, 42, has lived his whole life in the same house — a simple two-room brick structure with a tiny courtyard tucked down a narrow alleyway. But the bulldozers are coming. Like many of Beijing’s traditional neighborhoods, the cluster of homes where the Meng family lives is to be torn down in the name of a modernization not everyone desires.

The Meng home is a modest dwelling — no indoor plumbing, running water or central heating. Still, Meng would prefer to stay. He runs his business, a small glass shop, out of his front door.

But the future is coming and in it no room has been reserved for the Meng residence. They are not sure exactly what will be built in place of their home, perhaps a high-rise apartment building or a glitzy department store. But they know that more than a house will disappear when the neighborhood is plowed under.

Another world

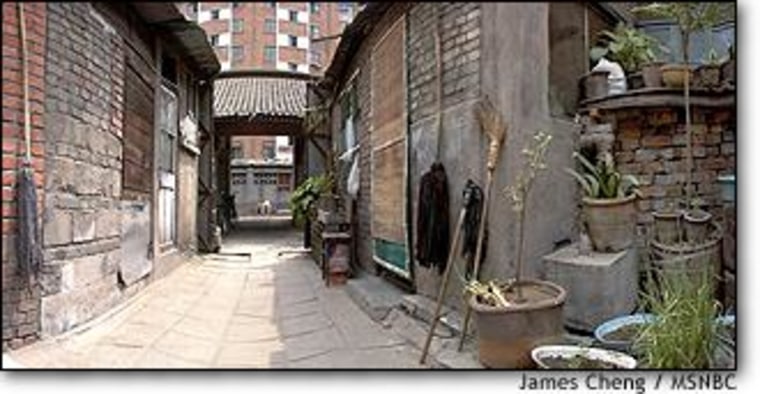

Since the early 1990’s Beijing has had undergone a major facelift. Many parts of the city are virtually unrecognizable to those who left only a few years ago. The change is particularly apparent in Beijing’s hutongs, a maze of narrow alleyways lined with single-story courtyard homes that made up the social fabric of Old Beijing. Such houses are relics of the Beijing past, built in traditional style with stone walls and beautifully sloping roofs.

To enter a hutong is to be transported back to the Beijing of a hundred years ago — a cozy sanctuary from the honking horns and exhaust fumes of a modern metropolis of nearly 12 million people. Unlike apartment buildings where each person rides an elevator to their floor then locks a door behind them, in the hutongs mothers sit on porches holding babies, children play jump rope in the street, men gather around a Chinese chess board and neighbors stand outside catching up on the latest gossip. Occasionally, one of the few surviving women from the era of feet binding may amble by with a cane. These communities are not far removed from the new buildings which tower high above, yet spiritually they seem to be a world away.

Tearing down the walls

The demolition of Old Beijing began in earnest after the Communists came to power in 1949. Ignoring the advice of his city planners, Chairman Mao began in the 1950s to dismantle the city walls to make way for the second ring road. He decided that the walls were a sign of feudalism, and that the bricks could be better used to build the New China.

Many residents fear that the destruction of hutongs will mean the loss of one of a cultural treasure. But the city continues to move forward with development plans and the hutongs are dissappearing at an amazing rate. In the process, residents often must relocate to high-rise buildings far away from the city center. Many Beijing residents, particularly the young, are happy to make the move, because the new apartments offer modern amenities unavailable in the hutongs.

But others are reluctant to leave long-time friends from the old neighborhood.

Beijing’s changing architecture is only one aspect of the dramatic changes taking place in the whole of China. The traditional image of a communist state where expressionless people walk the streets wearing dark colored Mao suits and carrying little red books has dissolved into a vivid modern world of mini skirts and blue jeans. Young people compete to keep up with the latest fads, whether it is the newest pair sneakers or the best mountain bike. The fear of being persecuted for being a “capitalist” is unheard of in today’s China, where people compete to own the newest cell phone model and like going to coffeehouses on saturday nights. The change in China is striking, and it is apparent everywhere.

But adjusting to the the dizzying pace of change has been difficult for people like Meng. He is resigned to leaving, but he dreads saying goodbye to his long-time friends and his childhood home. And unlike many who leave their neighborhoods at one time or another in their lives, Meng knows that he won’t be able to return.