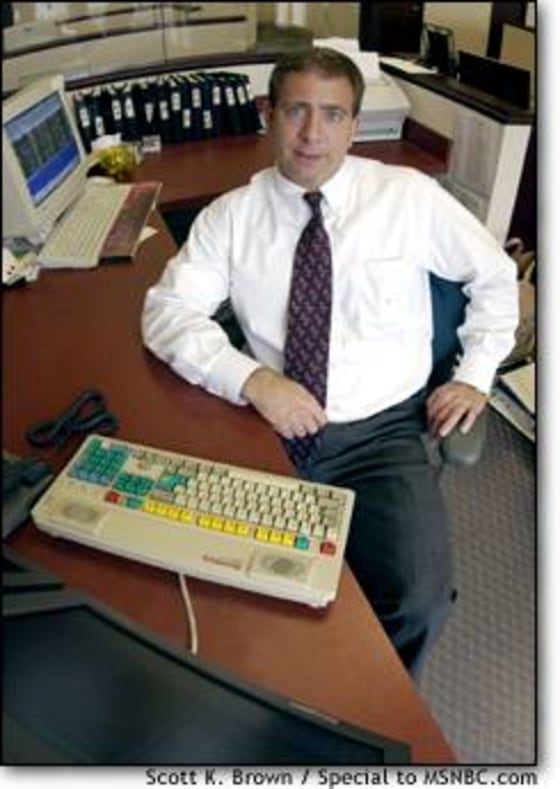

Kent Engelke, a money manager in this historic Southern town, is something of an anomaly amongst his peers. In 2002, when most in the brokerage business were muddling through a third consecutive year of declining stock prices, he chalked up his most profitable year to date, raking in more than $600,000 worth of new commissions for his firm, almost twice the industry average.

Engelke, who is 40 years old and has worked in the brokerage business since 1986, is modest about his achievement: “I got incredibly lucky,” he said. “I positioned myself to take advantage of a falling stock market, and it’s actually scary how accurate I’ve been over the last three years. I really believe I’ll be wrong over the next three because you can be never right all the time; there are too many moving variables.”

In 2000, at the height of the Internet boom, Engelke steadfastly refused to buy red-hot technology and telecom issues and moved his clients’ funds and his own retirement money into the relative safety of U.S. Treasuries and shares of community banks, convinced that the stock market was poised for a fall and that U.S. interest rates would decline. He guessed right, and to date has netted 300 percent in profits from his bond investments and a 100 percent gain from small-bank stock investments.

“I never thought I’d make that much money in my life,” Engelke said with a low voice. “I have a great deal more disposable income now, but my wife and I aren’t living beyond our means; you never know what might happen tomorrow.”

Engelke’s story is far from common. With most individual retirement accounts badly bruised by a three-year bear market, the last few years have been hard on most in the financial services industry. Individual investors have avoided shares like the plague, and Wall Street has suffered large job losses and a sharp drop-off in revenues as a result.

The average production level (basically trading commissions generated) for U.S. retail brokers has dropped 19 percent from its peak in 2000 of $485,478, while the average broker’s salary has declined 27 percent to $161,085 over the same period, according to the Securities Industry Association (SIA), an industry trade group. Industry employment is off by 11 percent from its zenith in April 2001, SIA data show, and cost cutting remains a priority at most Wall Street firms.

At Richmond-based Anderson & Strudwick, where Engelke is a senior vice president, revenue has declined along with the stock market, and the firm has let go of some under-producing brokers, replacing them with top producers from rival firms. “In this business, you’re only as good as the revenues you pull in,” Engelke remarked. “And it’s extraordinarily hard to get a job in this industry if you’re not producing.”

Engelke, who took home over $300,000 from trading commissions and bonuses last year, feels secure in his job and financially he is comfortable. But he still worries. He sees a number of outside factors that could hurt his livelihood, including more weakness in the economy and the threat of lawsuits from investors whose retirement portfolios have been trampled by swooning stock market.

“You have no idea who might decide to sue you. It could be your best client who you never suspected,” Engelke said. “If all of a sudden you’re faced with a $10 million lawsuit, regardless of whether you’re guilty or not, you’ll have a black mark against your name and you’ll probably never work in the industry again.”

The economy and the stock market also worry Engelke. “I’m very sensitive to it because I don’t make a salary — I make a bonus based on the money I make for the firm, so my income depends on the firm’s profitability. I have to do a certain level of production. If not, it’s hard to make ends meet each month,” he said.

With the economy fragile and the stock market’s direction still under debate, Engelke, who shuns flashy displays of wealth and drives a 1994 Volvo sedan, remains a cautious investor. His retirement account mirrors his clients’ investments. Holdings consist mainly of shares in community banks, zero-coupon bonds and, more recently, utilities and beaten-down techs and telecoms, areas where he sees the potential for growth.

“My wife and I are very big savers. Last year we maxed out our 401(k) plan and contributed all the money we could to our IRA,” he notes, adding that his biggest expenses in 2002 were a $105,000 two-bedroom condo he purchased in the Blue Ridge Mountains and the $25,000 he spent turning his attic into a playroom for his two young children.