Where did the SARS virus come from? Probably an animal, many experts say. One even speculates the germ might have come from a wild bird captured in southern China. But scientists have precious little evidence for exploring that basic question, let alone figuring out which animal it came from - or even ruling out the notion that the virus is a previously harmless human germ gone bad. Now the World Health Organization is pondering lab studies to get some new clues.

The question of where the SARS virus, a member of the coronavirus family, came from is not just a matter of curiosity. While it doesn’t directly affect efforts to contain the current outbreak, which is spreading from person to person, scientists say finding the ultimate source of the virus could help them prevent future outbreaks.

“If we’re ever able to control it, we want to make sure it doesn’t rise again,” said Dr. Robert Shope of the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, an expert on emerging diseases. “If you know the source, then you can at least design your control measures around that.”

So if an animal source can be identified, potentially dangerous populations might be vaccinated or even slaughtered. A 1997 outbreak of the flu in Hong Kong that killed six people was spread by poultry; Hong Kong slaughtered 1.4 million chickens in response.

Identifying an animal source could also help scientists find drugs to treat SARS, said coronavirus expert Dr. Mark Denison of Vanderbilt University. For one thing, that animal or its tissue might be used in experiments to test medicines, he said.

For another, if the ancestor of the SARS virus can be isolated, scientists can look for the crucial genetic changes that made the SARS virus so nasty. That could indicate targets for drugs and vaccines, he said.

Denison said his own guess is that the SARS virus emerged from an animal.

Scientists had hoped to get clues into the origin of SARS recently when two laboratories announced they’d determined the genetic makeup of the SARS virus. The idea was that by looking for similarities between the SARS virus and other coronaviruses, they might be able to figure out the new germ’s ancestry.

SARS VIRUS DIFFERENT FROM OTHERS

But the SARS virus turned out to be far different from previously known coronaviruses. Wherever it came from, it’s been evolving on its own for quite a while, not mixing genes with known coronavirus cousins.

And its genetic makeup didn’t even indicate whether it had come from animal or human virus ancestors, said coronavirus expert Brenda Hogue of Arizona State University.

“It’s possible it could be an animal virus we just haven’t seen before,” overlooked because it didn’t cause disease in the animal, she said. It could have jumped to humans by chance contact or by mutation that allowed it to infect human tissues, she said.

Experts say the most likely way of getting infected from animals is by living in close contact with infected creatures or slaughtering or butchering them, rather than eating them. Sufficient cooking should kill the virus.

Hogue said she believes the virus probably came from animals. But scientists must also keep an open mind about it’s being an unknown, benign human virus that turned dangerous through mutation, she said.

Coronaviruses are particularly prone to mutations. Scientists can look for evidence of a human origin by screening people, especially in China, for certain blood proteins called antibodies that indicate past exposure to something resembling the SARS virus.

WILD BIRD TO BLAME?

Dr. Michael Lai, a coronavirus expert at the University of Southern California, said the structure of the SARS virus genetic makeup shows some similarity to bird coronaviruses, but not known examples from chickens or other domestic animals.

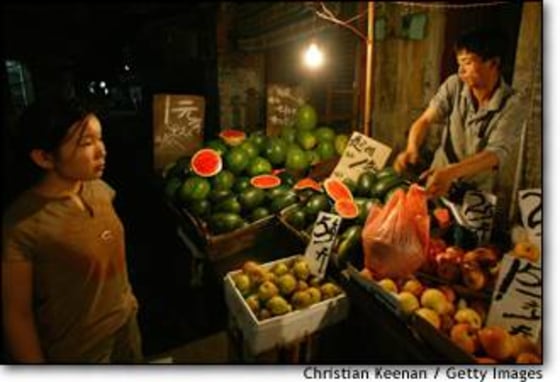

So that makes him speculate the virus came from a wild bird, he said. People in southern China, where the SARS epidemic began, like to capture wild animals for food, so maybe that’s how the virus made the jump to humans, he said.

The lack of antibodies to the virus in healthy people tested so far makes him think the virus hasn’t had much time to get around, suggesting the transfer from animals came perhaps in the last year or so, he said.

Francois Meslin, who coordinates a WHO team in Geneva that deals with diseases that can jump to humans from animals, said as yet there’s no evidence SARS came from animals.

In any case, WHO is studying an idea with some labs worldwide, including those in Australia, Canada and China: exposing various animals to the SARS virus to see if they get sick or become infected without symptoms, and shed the virus. That could give some clues about which animals might have been a launching pad for the human epidemic, Meslin said.

So far, scientists are just exploring the feasibility of such research. At the same time, WHO also plans further epidemiological work in China, looking for clues that link early cases to animals, farms or the slaughtering or butchering of animals, he said.

‘A VERY COMPLEX CYCLE’

As it stands right now, in trying to figure out what animals to include in the exposure study, he said, “we are totally working in a vacuum, since we have no epidemiology link.”

In any case, he said, finding the answer may be complex. One species may be the reservoir in nature that harbors a virus over a long period of time, but the virus may have to pass to a second species that has more contact with humans before people get infected. That’s the case with Ebola virus, which humans can pick up from ill or dead chimps but for which the ultimate reservoir is unknown, Meslin said.

“The cycle can be quite complex,” he said. As for SARS, “if it’s something that is deep inside a very complex cycle involving a rare reservoir species, we may never get to it.”