NASA researchers are literally holding the future of aerial monitoring in their hands — and it’s about 4 feet long. The agency is developing a new fleet of souped-up model airplanes that could be used for remote sensing and high-tech surveillance. The “small UAVs” are a civilian-friendly part of a revolution that’s already transforming the military landscape.

The sensor-equipped planes, tested here during the Jason Project’s annual educational expedition, are part of a category known as “unmanned aerial vehicles” (or “uninhabited aerial vehicles” for the politically correct).

That makes them distant cousins of flying robots such as the Pentagon’s Predator and the Global Hawk — as well as the Altair, NASA’s version of the Predator, and a solar-powered pilotless plane called the Helios.

NASA’s small UAVs are a far cry from those multimillion-dollar machines, however: Some of the early prototypes are basically $200 radio-controlled model airplanes. It’s what’s inside that makes them special: miniaturized video cameras, microspectrometers, thermal imagers, magnetometers.

“Remote control has been around for a long time,” said Patrick Coronado, an engineer and remote sensing scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. “But doing remote control and science is another story.”

Coronado foresees a time when commercial companies could sell sophisticated UAVs for a couple of thousand dollars, or rent them by the day or the week. “Within three years, we would have platforms like the one you see today be available for specific applications,” he said.

Some small UAVs are already showing up for domestic use: The U.S. Coast Guard, for example, has been experimenting with the Condor craft for sea patrols, and Philadelphia TV stations have bought BAI’s camera-equipped Javelin planes for monitoring beaches.

The UAVs being developed by NASA could be used for far more sophisticated tasks: They could pick up the spectral signatures of fungal infestations in crops, algae blooms in agricultural ponds or dead zones in the oceans. The UAVs could hunt for meteorites in the Antarctic, monitor Western wildfires or take on kamikaze missions to study hurricanes and tornadoes. They could carry the equipment to create an instant cellular-phone network in remote areas.

Small UAVs could play a role in homeland security as well: Remote-control planes equipped with thermal imagers could patrol the country’s borders on autopilot, looking for the heat signature of anyone trying to make a surreptitious crossing.

NASA doesn’t plan to market the sensor-laden planes itself, Coronado said.

“What we do is develop all the necessary technology that will acquire and process all direct data,” he explained. The UAVs would fill in a significant gap between satellite imagery and on-the-ground observations, he said.

Spy satellites can produce images with a resolution of less than 1 meter — meaning that an object 1 meter or roughly 3 feet wide might take up a single pixel on the digital picture. But the satellites used for scientific research, such as NASA’s Terra and Aqua spacecraft, are less precise, with a resolution of a kilometer or so.

“In order to do remote sensing, just acquiring satellite data is not enough,” Coronado said.

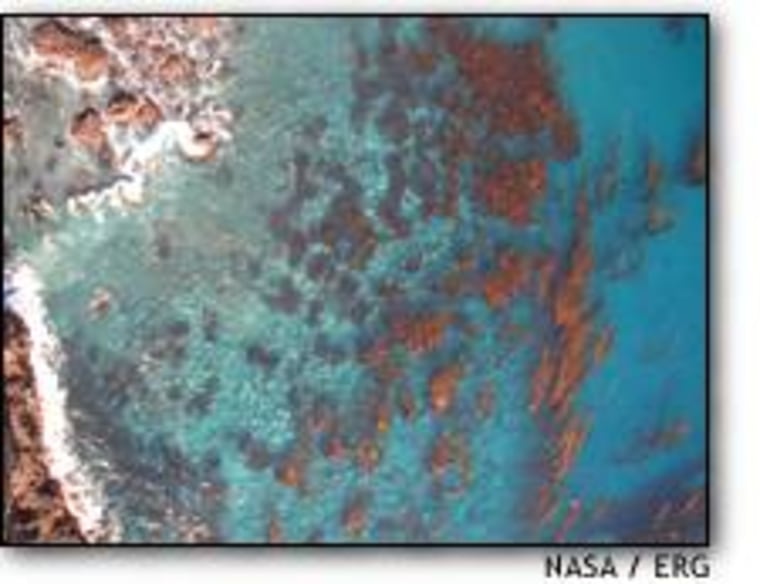

Sensor-equipped UAVs could flesh out the picture provided by scientific satellites by making a methodical sweep over an area of interest — for example, the delicate kelp forests off Anacapa Island. Detailed maps of marine vegetation and chlorophyll fluorescence could be made regularly, showing how weather patterns or other environmental factors affect the plants’ growth and decline.

“We’re especially tracking this area because of El Niòo,” NASA education specialist Sallie Smith said.

Imagery from the UAVs was compared with real-time data from the Terra and Aqua satellites. Students worked alongside NASA scientists to launch the planes, and Coronado said the educational purpose was at least as important as the scientific return.

“The tool is a good ‘gotcha,’ but we want the students to be aware of their environment ... and understand the concept of remote sensing,” he said.

The Jason Project outing follows up on the small UAVs’ first real-world test at Bolivia’s Iturralde Crater last September. The planes were outfitted with magnetometers to map the crater and determine whether it was formed as the result of a meteor impact.

After the Jason Project, the NASA team plans to bring its mobile remote-sensing operation to Utah, where they will meet with U.S. Forest Service experts to discuss the technology’s potential for monitoring wildfires.

The planes being tested on Anacapa Island can carry a payload of about 4 pounds and fly for up to 45 minutes. Because the electric motors are powered by expensive, non-rechargeable lithium batteries, each flight costs at least $100, Coronado said.

NASA’s gasoline-powered UAVs can carry twice the payload and fly for four times as long.

“If you want range, if you want speed, if you want altitude, if you want more cargo ... then you have to go to gas,” Coronado said.

The Jason Project didn’t use any gas-powered planes because of environmental concerns as well as local regulations. That illustrates the kind of regulatory fog that future eyes in the sky may have to navigate: NASA’s UAV program is following the rules that govern model airplane flight, which means the planes should stay under 400 feet in altitude near airports. But depending on the setting, the altitude could go much higher.

Coronado said the guidance systems for civilian UAVs have to be built with double and triple redundancy, in contrast with the rough-and-ready battle machines fielded by the Pentagon. NASA also has to be more worried than military officials about operating over populated areas.

“If something goes wrong, [the military controllers] can just hit the ‘blow-up’ button,” Coronado said.

Despite the different operating environments, Coronado said the military and civil programs for small UAVs were “starting to converge.” NASA is exchanging information with the Naval Research Laboratory and other military groups involved in UAV development, he said.

As an educational effort, NASA is also hoping to collaborate with teachers, students and hobbyists who belong to the Academy of Model Aeronautics. Smith said eight to 10 schools would be selected to draw up remote-imaging experiments with NASA support, then work with model airplane clubs to turn their proposals into high-flying reality.