Waking up in Havana feels wondrous, even surreal. Time seems to have stopped. From the look of the cars, or what’s left of them, it’s the 1950s. And nobody is hurrying to work. The hush of dawn lasts until 10 in the morning, when the grocery stores finally open. But the faint odor of petroleum from the nearby oil refineries already hangs in the air. It will last all day, until a fresh sea breeze washes it away at evening.

IT’S NOT ONLY the sight of American-made cars from an earlier era — a 1951 Chevrolet parked on its axles, a 1955 Studebaker in need of a paint job, a 1954 Chrysler cab in front of my hotel — that lends Havana a feeling of stopped time. It’s the sleepy pace of daily life. There’s no big-city bustle in Fidel Castro’s capital, population 2.2 million, unless you count the crowds that pack the bus stops under the midday sun or the tourists that jam the clubs and hotels at night.

From every corner you can see empty stretches of impoverished streets paved with dirt, dilapidated buildings with once-ornate facades now crumbling and blackened with age.

Though hardly a cure for the poverty, joyous Cuban music can be heard everywhere day and night. I’ve come to think of it as the holy order of the clave, and it may be something of an antidote to bitterness. I have no other way to explain the graciousness and openness of the Cubans I met. Even the persistent street hustlers selling cut-rate cigars and the pretty, equally unavoidable prostitutes in the dance halls were remarkably pleasant, their aggressiveness just a form of friendly persuasion.

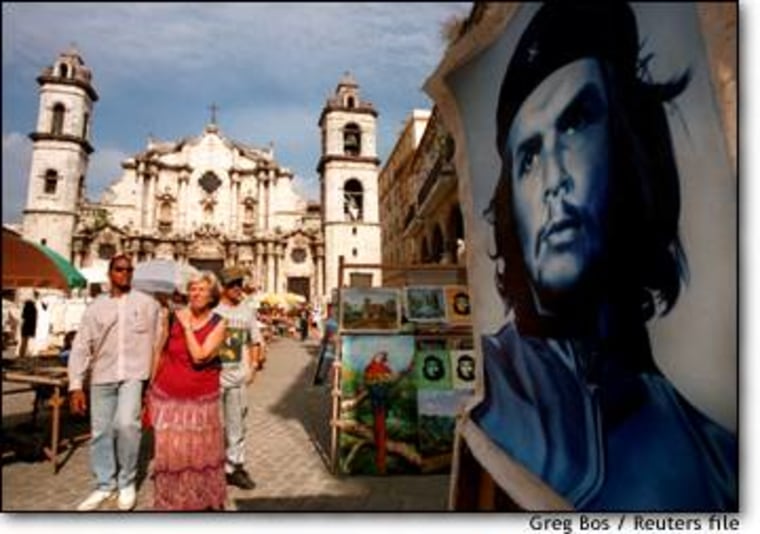

Che, in his beret

Then, of course, there’s the stopped-time image of Che Guevara in his military beret, a distant if famous memory of the ’60s, but still seen everywhere in today’s Cuba. Che’s handsome, bearded face — on billboards and postcards, on T-shirts and posters — is not just an emblem of the Revolution. It is the symbol, some would say relic, of a state religion.

If you go to Che’s shrine in Santa Clara southeast of Havana, where he is buried beneath a gigantic Soviet-style statue that commemorates both his decisive military victory over Fulgencio Batista’s army in 1958 (after which the dictator fled the country) and Che’s departure for Bolivia in 1965 to foment another (this time unsuccessful) revolution, you will see him heroically outlined against the sky.

The words “Hasta la victoria siempre” (“Always to victory”) are inscribed on the statue’s huge granite pedestal. He carries his rifle in one hand. His other hand, wounded in battle, is wrapped in bandages. The dimly lighted crypt beneath the monument, where Che’s bones are interred in a wall vault along with 30 others who died with him in Bolivia, has the sacred aura of a martyr’s burial place.

The great man himself, Fidel Castro, far from being preserved in amber, is a constant living presence with his own aura of grandeur and mystery. Yet the 75-year-old father of the Revolution — whose ideas are law and, however dubious, communist policy — is nothing if not a reminder of the past: a walking, talking embodiment of stopped time.

JOKING ABOUT FIDEL

Cubans who apparently revere “El commandante” muse out loud about his longevity, wondering whether he will last another decade or more, which keeps them in a state of suspense, if not suspended animation. But for all their reverence, they also regard him as a figure to be satirized. One of them passed on this joke, clearly a measure of their ambivalence:

“Fidel dies and goes to heaven. But he’s turned away. A room has been prepared for him in hell. When he gets down there, he doesn’t like the accommodations. So he tells the Devil he has to go back to heaven to get his luggage. The Devil, no fool, sends two assistant devils to bring back his luggage. When nobody in heaven answers their knock, they climb over the wall. A passing angel sees them. “Fidel got down there not five minutes ago,” the angel says, “and already we have rafters.”

The distance to Cuba from the United States is only 90 miles or so, as the crow flies. But because of the U.S. trade embargo dating from as early as 1960 and because of subsequent legislation, American travelers cannot fly direct. With some exceptions both for travelers and airlines, they must go via Mexico or Canada or from any other country that has commercial air service to Havana.

U.S. citizens aren’t prohibited from actually going to Cuba, they’re just not allowed to spend money there unless they’re “authorized” travelers.

And who are these lucky people?

Journalists, government officials, once-a-year visitors with “close relatives in … humanitarian need,” professionals attending conferences, amateur or semi-pro athletes, students or teachers in specific educational programs, members of certain international organizations, academic researchers, scholars and “licensed” travelers granted the right by the U.S. Treasury Department “to engage in travel-related transactions,” usually for cultural purposes.

Authorized or not, more Americans than ever are taking the trip. About 170,000 U.S. tourists went to Cuba in 2000, says Luis Diaz de Aguiar, an official Cuban guide who lives in Havana. If true, that’s almost triple the number of U.S. tourists in 1995, roughly 60,000, only 20 percent of whom made the trip legally, according to Christopher P. Baker’s “Cuba Handbook.”

Carlos Dell’Acqua, who heads Cuba Cultural Travel, the Costa Mesa, Calif.-based travel agency that booked my trip, says there are no accurate figures because all are “guestimates,” not actual counts. Other tourist experts put the number at about 50,000 Americans who will visit this year, with or without U.S. approval. Cuban officials have said that altogether about 1.6 million tourists visited in 1999.

10 DAYs ON THE ISLAND

I went to Cuba in February with a licensed group of U.S. tourists on a 10-day outing arranged by the Seattle-based museum Experience Music Project. There were 30 of us. Most flew from Seattle via Houston to Cancun, Mexico. I flew from New York directly to Cancun, where we all boarded an Aerocaribe jetliner for the hour flight to Havana.

Sitting next to me was a Cuban in his 60s, from Miami. As we descended toward Havana Airport, he kept looking out the porthole at the sparse pinpoints of light below. “Poquito! Poquito!” he said, grimacing sadly and holding up his thumb and index finger like a pair of tweezers. Havana’s pale flickering, a poor match for Miami’s electric blaze, seemed to evoke contradictory feelings in him of anguish and schadenfreude.

Once on the ground, it was even darker. The airport felt deserted. Perhaps it was the time of night. (We arrived at 9:40 p.m.) Cuban passport control checked us through in what looked like a refurbished hangar. The half-hour drive into the city by bus confirmed what we’d seen on our descent: Streets lights in Havana are few.

Nor are there many neon signs or any McDonald’s arches; and the only billboards I ever saw typically advertised patriotic slogans like “La Solidaridad No Se Puede Bloquear” (“Solidarity Can’t Be Blockaded”). Even the graffiti is patriotic: “Vivimos para la patria” (“We live for our country”). It was scrawled on Havana’s sea wall along the Malecón, a wide roadway with a broad sidewalk that many city residents treat as an outdoor livingroom or lovers’ lane, depending on the time of day.

SALSA MUSIC LIKE A DREAM

That first night at the Golden Tulip Parque Central — a 279-room hotel with a five-star rating and the interior of an upscale motor lodge — I flung open the French windows of my seventh-floor room to get rid of the stale, air-conditioned smell of old cigarette smoke. Like a dream, salsa music wafted in from a dance hall across the street. I was in a state of bliss for the next four hours, until 3 a.m. I couldn’t have hoped for a better introduction to Cuba.

There are seven five-star hotels in Havana and another eight in the rest of the island (along the beaches, mostly in the resort area of Varardero on the northern coast, east of Havana).

From my experience at the Parque Central and two other hotels — the Tryp Península Varadero (a beach resort in Matanzas) and the Hotel Trinida del Mar (another beach resort in Trinidad) — a five-star rating in Cuba means comfortable accommodations but nothing spectacular (and sometimes, for short periods, no running water). These three hotels also lacked character. They offered varying degrees and styles of a homogenized atmosphere that you can find anywhere from Cape Cod to San Diego. But unless you go to a casa particular (the Cuban equivalent of a B&B), which requires special permission,there’s no way to beat the rates. They range from $75 a night (and up) to $130 (and up).

For the same money, though, I would have chosen to stay at Havana’s Hotel Nacional, which not only has a five-star rating and rates beginning at $81 but character to spare. It glows with Spanish-style grandeur and art-deco elegance; and its literary history alone makes it memorable. (Graham Greene spent a lot of time there.)

What’s more, unlike the major tourist hotels, which are strictly reserved for foreigners, the Hotel Nacional accommodates Cubans who can afford $15 to spend the day at its outdoor pool-cum-garden (with lunch and towel included). Tourists not registered at the hotel can spend the day at the pool for the same rate, too.

Considering that as many as nine out of 10 Cubans work for the state, and given their uniform government salaries of about $25 a month (whether they’re doctors or teachers, factory workers or bus drivers), very few Cubans can afford to go swimming at the Nacional. But some can — those who have managed to tap into the parallel economy of hard-currency U.S. dollars that has taken hold with Castro’s permission and, lately, encouragement. Which makes the Nacional one of the more charming places where you can easily meet enterprising Cubans or strike up conversations with locals who are relatively well off.