The sun-bleached bones are kept in a cardboard box in a locked cabinet — a skull, a thighbone, several ribs and vertebrae, pieces of a pelvis. To Lori Baker’s trained eye, the remains found in a lonely corner of South Texas near the Rio Grande tell of a boy, about 13. Some of his clothing was homemade, and he carried a dark cloth knapsack bearing the name of a Mexican university. Baker, a forensic scientist at Baylor University, is sure the boy died while trying to enter the United States illegally, one of hundreds who perish annually along the hot, dry Mexican border.

“They are people, too,” she said of the illegal immigrants, many of whom end up in poorly marked graves in paupers’ cemeteries. “They deserve to be buried and have their families know what happened to them.”

Baker is beginning an ambitious project to identify the bodies of hundreds of illegal immigrants found dead along the border and share her findings with their families back home in Mexico and Central America, who have not heard from their loved ones since they left for the United States.

Nearly 1,400 suspected illegal immigrants died along the nation’s southern border in the past four years, according to the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection. Of that number, 470 were found in Texas. More than 600 bodies found since 1999 remain unidentified.

Searchable database

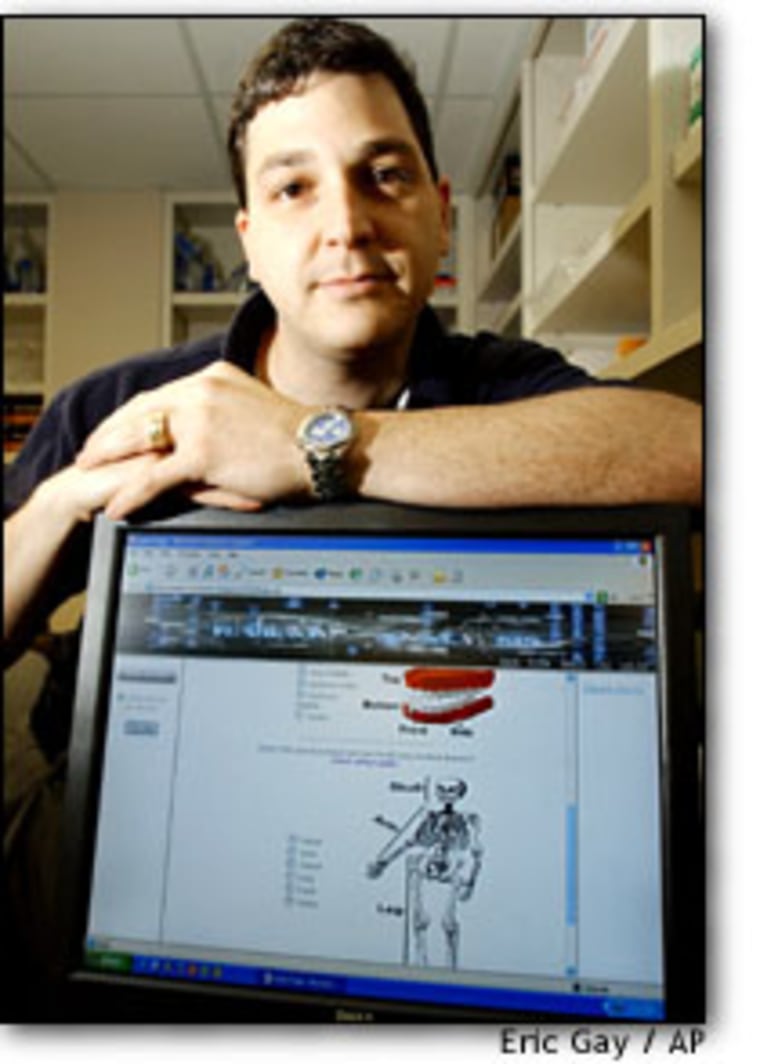

Baker’s husband, Erich, a computer science professor at Baylor, will assist the project. She will extract DNA from the remains — from bones, tissue, hair or other sources — and gather other physical clues, and he will compile the information into a searchable, online database.

The database will list information on the immigrant, such as approximate age, height and weight, any distinguishing marks on the body, dental work, where the body was found and if any clothing or jewelry was with it.

The families of the missing will be able to complete an online form asking them to provide a detailed physical description of their relative, as well as what the person probably wore, where they were last seen and their possible destination.

If a possible match turns up, Baker will send the family a do-it-yourself DNA swab kit to provide the samples she needs to compare with genetic material from the body.

Baylor, the world’s largest Baptist University, agreed to provide limited funding of Baker’s work. She will also seek money from private foundations. She estimates she will need $800,000 for the first few years.

“It’s going to take a lot of time and effort and lots of samples from families before we start seeing success,” she said.

The Bakers envision that Mexican families without computers will work through government agencies. They also plan to get the word out in U.S. communities with large immigrant populations.

Useful work

The Bakers’ work will be useful even if only a small percentage of bodies are identified, said Nestor Rodriguez, co-director of the Center for Immigration at the University of Houston.

“There’s almost nothing as difficult and painful for a family than not knowing what happened,” he said. “I’ve spoken to mothers who haven’t heard anything for more than a decade and they’re still looking.”

Baker’s first success involved the skeleton of a young woman found in the Arizona desert near Tucson, Ariz., last December. A Mexican voter card was discovered close to the remains, which gave Baker a name and a lead on finding family members for the DNA needed to make a match. The woman was eventually identified as Rosita Cano, from a small town on the Yucatan Peninsula.

Cano’s mother told The Arizona Republic of her relief when learning of her daughter’s fate. “It feels awful at first, but I am at peace now that it has been confirmed,” she said.

Bruce Anderson, an anthropologist for the Pima County medical examiner in Tucson, said the county is considering sending Baker about 100 DNA samples of suspected illegal immigrants for inclusion in her database.