Seemingly oblivious to the large group of crocodiles resting on a nearby sandbank, four rare black storks sun themselves in South Africa’s Kruger National Park. But the real danger to these elusive birds is not the razor-sharp teeth of the crocodiles. It is the teeth of chainsaws thousands of miles to the north, where old growth forests — habitat vital to the bird’s survival — are being mowed down.

InsertArt(2050840)THE BLACK STORK is one of many species that scientists fear could follow the dinosaurs down the road to extinction because of human activities such as logging, farming and building dams.

A U.N. report on Earth’s vital signals, prepared ahead of this week’s Earth Summit II in Johannesburg, warned that nearly a quarter of all known mammal species and 12 percent of known bird species are regarded as globally threatened.

Humanity’s impact on biodiversity is high on the agenda and conservationists hope historians do not look back five decades from now and see it as a missed opportunity to avert what could be the greatest loss of life on the planet since the death of the dinosaurs.

PAST EXTINCTIONS

Mass extinctions have occurred five times in the four billion year history of life. Many credible scientists fear that the sixth mass extinction in the planet’s long history is unfolding — a doomsday scenario dismissed as alarmist by some.

The past extinctions are loosely defined as moments in geological history when half or more of all marine species — which today are preserved in fossils — die off in a short period of time. (Terrestrial life is also not believed to fare well during these periods).

According to one book on the subject, “The Sixth Extinction,” by Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin, the grim reaper first visited Earth on this vast scale 450 million years ago.

The second mass extinction took place 100 million years later. In the Triassic period 250 and 200 million years ago, two mass extinctions snuffed out countless species.

Then, 65 million years ago, scientists believe the dinosaurs were killed off when a giant meteorite collided with Earth.

Some expect the sixth extinction will have been brought about entirely by people.

“In the next 50 to 100 years there is a good possibility that there could be a mass extinction of species which is human-induced,” said Susan Lieberman, director of the Species Program for the World Wide Fund for Nature. “We are heading for a crisis. And we have to act now if we are going to avert this.”

EXTINCTION ESTIMATES

Leakey and Lewin estimate that perhaps 50 percent of all species will become extinct in the next 100 years. Others take a more measured view but agree that a crisis is looming.

Statistician Bjorn Lomborg argues in his controversial recent book, “The Skeptical Environmentalist,” that we could lose about 0.7 percent of the planet’s species over the next five decades — an estimate far below many but one which he says is “not trivial.”

As for species already lost, the Committee on Recently Extinct Organisms says at least 70 species of fish, birds and mammals have disappeared since 1970.

The WWF, for its part, says 81 freshwater species of fish are recorded to have become extinct in the last 100 years. The majority, 50, were endemic to Africa’s Lake Victoria and vanished because of the introduction there of the voracious Nile perch.

Experts also agree that countless others species that have never been discovered — notably in tropical rain forests and marine ecosystems — have probably become extinct as well.

STORKS’ STORY

The black stork and wild dog, two species in Kruger which nobody disputes are endangered, sum up the threats to many.

The black stork’s global population is about 7,000 to 9,500 nesting pairs, according to ornithologist Maris Strazds. The biggest population, about 4,500 to 6,000, is found in Eastern Europe.

Unlike their more gregarious and numerous cousin the white stork, which often nests on farmhouses in Eastern Europe, the shy and reclusive black stork prefers to decamp far from the madding crowd in the quiet of old growth forests which are being targeted for exploitation.

East European “black storks nest in pine trees which are on average around 200 years old. And trees of that age are very much in the sights of loggers,” said Strazds.

Strazds said laws in Latvia, his home country, mandate a 50-acre logging ban around their nests, but land owners often simply cut their trees down and plead ignorance to the presence of the birds.

“The Latvian black stork population is bound to fall to some 500 pairs (from about 900 pairs) because of logging ... but if we do not observe nest protection rules, it could fall rapidly to 20-odd pairs in two decades or so,” he said.

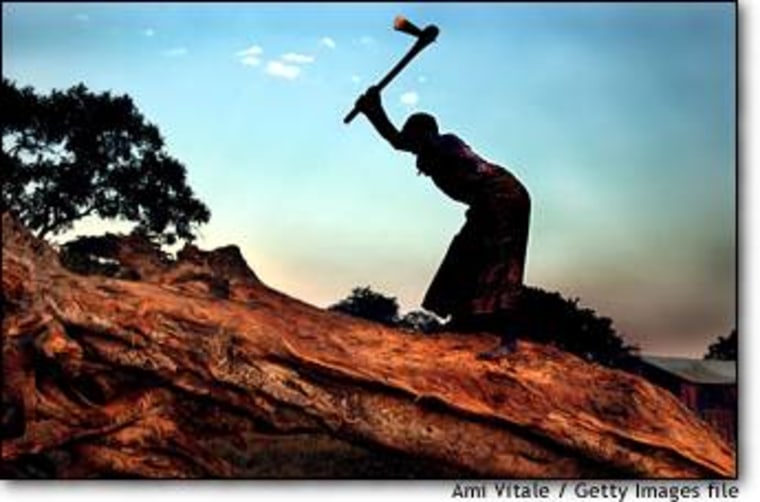

Habitat destruction by people is probably the primary cause of species decline.

The U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that forests, which cover around a third of the world’s land surface, have diminished by 2.4 percent since 1990.

The biggest losses have been in Africa, where 130 million acres or 0.7 percent of its forest cover has vanished in the past decade. Luckily for Kruger’s black storks, their home habitat is at least protected.

WILD DOGS DWINDLE

Another Kruger resident, the wild dog, highlights the age-old persecution of predators by farmers.

Also known as the “painted wolf” because of the splashes of vivid color across its coat, the wild dog is the second rarest carnivore in Africa after the Ethiopian wolf.

A highly social animal that hunts in packs, its numbers have been reduced to an estimated 5,000 — mostly in parts of southern Africa and Tanzania — mainly because of shooting and poisoning by farmers worried about their livestock.

But even in a conservation stronghold such as Kruger, its numbers are dwindling.

“The number of wild dogs here is down to under 200 now from over 400 a few years ago, and we really don’t know why,” said Kruger zoologist Gus Mills.

This is a cause for concern because, given their reputation with farmers and their small numbers, it seems doubtful they could survive for long outside protected or very remote areas.

OTHER THREATS

There are other threats to species besides habitat loss and persecution, including global warming and pollution.

Humanity’s soaring population, especially in developing countries, is seen as putting added pressure on land and scarce resources, to the detriment of the other species we share the planet with.

The WWF’s most recent Living Planet Index — based on population trends of hundreds of species of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fish — has fallen 37 percent over the past 30 years.

“Current human consumptive pressure is unsustainable,” the WWF claims.

The U.N. report on Earth’s vital signals, called the Global Environmental Outlook, is online at www.unep.org/GEO/geo3.

© 2003 Reuters Limited. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Reuters content is expressly prohibited without the prior written consent of Reuters.