In a spin of the wheel born of both desperation and optimism, Detroit expects to become the largest U.S. city to capitalize on Americans’ love affair with gambling later this year with the opening of three downtown casinos. But while city officials hope the taxes generated by the casinos will fuel a renaissance in the blighted city, others worry that the opulent riverfront establishments will merely create a glittering oasis on the edge of an urban wasteland.

Mayor Dennis Archer, who championed the casino referendum approved by Michigan voters in 1996, dismisses such concerns, maintaining that lessons have been learned from mistakes of other cities that have embraced legalized gambling — notably Atlantic City and New Orleans.

“I think what you will find in the city of Detroit is something that will be highly competitive, user friendly, family oriented and therefore very, very successful,” Archer told MSNBC. He said he expects that the trio of casinos will create the equivalent of 11,000 full-time jobs, gross $1.5 billion a year and generate about $130 million annually in taxes.

Many questions still surround the city’s impending entry into the realm of instant risk and reward, including completion of land acquisition for the permanent casinos and state approval of gaming licenses for the operators.

But in a show of confidence, the casino developers - the MGM Grand; a partnership of Circus-Circus and local investors; and the “Greektown” group, which is led by the Sault Ste. Marie Chippewa tribe - have begun work on three temporary casinos. The temporary establishments, expected to cost between $115 million and $200 million each, will be scattered around the city, occupying a former bread factory, an old Internal Revenue Service office building and an converted warehouse in the Trapper’s Alley tourist district.

Barring delays in the licensing process, the temporary casinos are expected to open in either the third or fourth quarter of 1999, with permanent casinos - costing between $525 million and $800 million apiece - due to be completed no later than four years later.

Keen interest elsewhere

The unfolding of the green felt in Detroit will be closely watched by the gaming industry, which has seen the rapid growth of the 1980s and early ’90s slow in recent years. It also will be carefully reviewed by officials in other cities and states that already have telegraphed their interest in getting a piece of the action, including the mayors of Baltimore, Chicago and New York City.

But lest those officials forget the divisions that legalized gambling tends to open in a community, they will be forcefully reminded by the Detroit experience.

Strong protests and an attempt to force a special recall election to remove Archer from office have followed the selection process for casino developers and a sudden change of plans on the location of the project.

And even supporters of the city’s plans express concerns about the trade-offs: Crime, which has declined substantially since the days when Detroit earned the sobriquet “Murder Capital,” is likely to increase, as are certain social ills.

N. Charles Anderson, president of the Detroit Urban League, says his agency and other social services providers are gearing up for an increased caseload.

“What we have learned is that when casinos hit towns, there is an increase of child abuse, child neglect, spousal abuse, domestic violence situations,” he said. “So we are concerned about that and whether we can be effective responding” to the problems.

The recall effort has opened an unusual chasm in a city where 76 percent of the residents are black: Organizers contend that the African-American mayor was guilty of discrimination when he selected MGM Grand’s bid over one by Don Barden, a black businessman with experience operating an Iowa riverboat. The decision meant that none of the three casinos will have majority black ownership.

“We are very upset,” said Minister Malik Shabazz, a member of the Community Coalition group that is spearheading the petition drive to force the city to hold a special election later this summer. “… In the Jewish community, this would not happen. In the Greek community, in the Italian community, in the Arab community, this would not be tolerated.”

Archer defends the selection process as being based on the city’s needs.

“The people have said what is important ... is what is in the best interest of … the city of Detroit, not in terms of a particular ethnic group or who should be the owner,” he said, referring to a ballot initiative narrowly rejected by voters last year that would have replaced MGM Grand with Barden and a new partner - pop icon Michael Jackson.

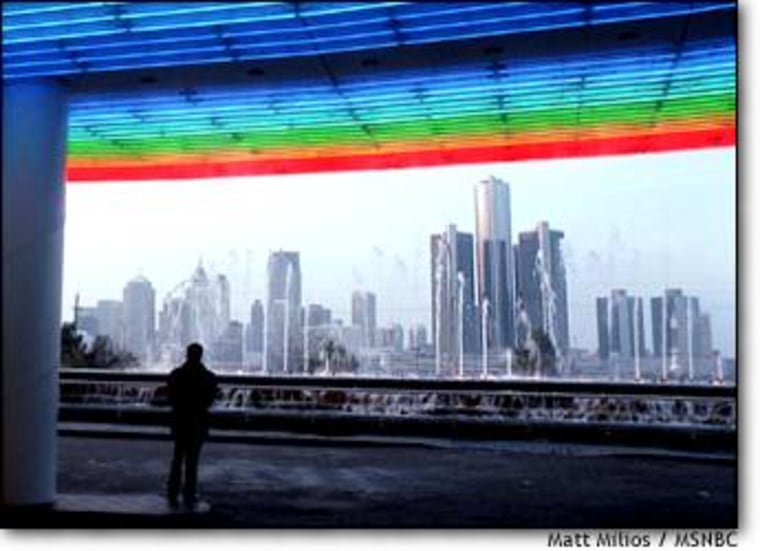

Neighbors and some small-business owners also rose up in opposition after Archer and the City Council last year abandoned plans to build the permanent casinos at three separate sites in the main business district and instead announced plans for side-by-side casinos on a 57-acre site on the Detroit River.

‘Making decisions as they go’

“They just turned on a dime and said ‘We’re going to put (the casinos) over there,’ … and they did this quickly without any input from professional planners,” said Anne Scott, a spokeswoman for the hastily formed Riverfront East Alliance (REAL), which continues to fight the decision. “… It’s like they’re just making decisions as they go. When you do that ... you fail in the end.”

The city and developers in January reached agreement on a plan to acquire the land for nearly $250 million, which will require the condemnation of 55 businesses and 260 apartments, according to REAL. Some residents of the area, which in recent years has been one of the city’s bright spots in terms of redevelopment, have indicated they might sue to try to stop the condemnation, saying it is illegal to seize private property to benefit private businesses.

But despite the last-ditch efforts to derail the process, completion of the deal is rapidly taking on the air of inevitability.

This in turn leads to the central question of the city’s venture: Can Detroit transform its image as a gritty industrial center beset by a host of urban ills into that of destination city?

Some stock analysts and gaming industry observers are skeptical.

“Even Atlantic City at its worst, people were still going to the beach and they were still visiting the Boardwalk,” said Matt Connor, features editor of International Gaming and Wagering Business magazine. “I don’t know if Detroit has a tourist center where people come from out of town or the next state over to visit.”

Doubters also note that the casinos will face stern competition from a sparkling new casino just across the river, in Windsor, Canada, and from 15 tribal casinos in Michigan, with more on the way. They also will be taxed at 25 percent - the highest rate of any land-based casino in the United States.

The change of plans on where the casinos would be built also heightened concerns that businesses in the downtown area would gain little economic benefit from casino visitors since the riverside complex would be isolated from the downtown by Jefferson Avenue, a major thoroughfare.

“It was represented that the casinos … would have a ripple effect and would be significant economic generators beyond their walls,” said John Mogk, a law professor at Detroit’s Wayne State University who has been involved in numerous redevelopment projects in the city’s downtown. “Now if you take that at face value .. then they’re in the wrong spot … (because Jefferson Avenue) isolates the casino activity from the city.”

But casino developers say that city officials have crafted the deal to ensure that Detroit doesn’t become another Atlantic City, where visitors to the luxurious hotel-resorts rarely encounter the poverty of the city at large. Unlike in New Jersey, where the state collected nearly all of the taxes, 55 percent of the money generated by the Detroit casinos will go directly to the city.

“Atlantic City is built facing the ocean; these casinos will be built facing the city,” said Marvin Beatty, an investor in the Greektown casino. “… It was our belief that it was necessary …to face the community and interface with the problems that face Detroit and southeast Michigan and to try to resolve some of them.”

Despite the protests and considerable early skepticism, some stock analysts who were initially doubtful about the prospects for gambling in the depressed auto capital have warmed to the idea after seeing Casino Windsor rake in money at a record pace at its glittering new casino, which opened on July 29. Eighty percent of the Canadian casino’s customers cross over from the United States, studies have shown.

Cautious optimism

John Rohs, a gaming analyst with Schroeder Associates, said Detroit’s casinos will be able to draw on a population of 9.3 million within a 150-mile radius, which encompasses vast affluent suburbs in southern Michigan.

But Schroeder recently cautioned investors that while the firm is “cautiously optimistic” about the potential in Detroit, “Political hurdles and the unforeseen ability of casinos to lure patrons downtown still pose decided risks.”

Stuart Linde, a gaming analyst with Lehman Brothers, is more bullish.

“We rate Detroit as one of our favorite emerging markets,” he said, adding that Lehman believes that revenues of $2 billion a year, when Windsor is included, are possible when the permanent casinos are opened.

It is not clear to what extent a success in Detroit would encourage neighboring markets and other cities and states to pursue new gambling initiatives, especially casinos. But most observers agree that nearby states like Ohio, Indiana and Pennsylvania would find it hard to resist when they see their citizens feeding the till in Michigan. Much the same thing occurred when riverboat gambling quickly spread up and down the Mississippi River after Iowa’s first floating casino dropped anchor on April Fool’s Day in 1991.

And with mayors in other big cities, including Richard M. Daley in Chicago and Rudolph Giuliani in New York, tired of watching profitable riverboats and gambling cruise ships operating within miles of City Hall, many observers believe a new expansion of gambling could occur if Detroit’s venture goes well.

“Neither (Atlantic City nor New Orleans) augured well for gaming in major downtown markets,” said Rohs, the stock analyst. “I think people will be watching Detroit very close to see if the omens are better.”