The United States passed up an opportunity to apprehend two of the men thought to be directly involved in the bombings of its embassy in Kenya last year because of a dispute between the FBI and the State Department, senior law enforcement officials and diplomatic sources said Thursday. The twin bombings in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, killed over 250 people, including 12 Americans.

THE DAY after the Aug. 7, 1998, attacks, two of the suspected bombers were arrested in Sudan, which then offered to turn them over to the FBI, according to accounts from two senior U.S. law enforcement officials and diplomatic sources. Those accounts were also confirmed by documents obtained by MSNBC.

The law enforcement officials said that evidence suggested that the men held in Sudan were directly linked to the Nairobi bombing and that they had intimate knowledge of the operations of the alleged guerrilla chief Osama bin Laden. Nonetheless, these officials said, the State Department refused to allow an FBI team to travel to the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, to discuss apprehending the suspects.

One senior law enforcement official said the State Department, in blocking the FBI from pursuing the lead, noted that Sudan has been listed for over a decade as a state sponsor of terrorism. Yet Sudan, the official said, had asked only for a “dialogue” with the United States toward restoring a more normal diplomatic relationship.

“The rational was weak and it was, in my view, unconscionable,” the senior law enforcement official said. “State simply would not let us even discuss the issue with the Sudanese.”

Joe Reap, spokesman for the State Department’s counter-terrorism division, said Thursday that because a criminal investigation was underway, “all questions must be referred to the FBI.”

FALSE PASSPORTS

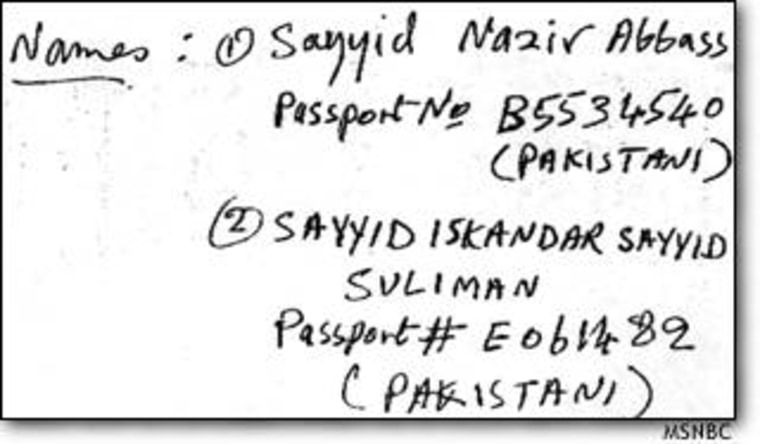

The documents obtained by MSNBC indicate that Sudanese authorities arrested the two men the day after the bombings as they stepped off Kenya Airways flight from Nairobi to Khartoum. The documents, which Sudan provided to the FBI through an intermediary, identified the men and their Pakistani passport numbers as Sayyid Nazir Abbass, passport No. B5534540, and Sayyid Iskandar Sayyid Suliman, passport No. E061482.

The U.S. law enforcement sources said that while the passports and the names were likely false, the two men were believed to have been directly involved in the Nairobi attack. More importantly, another U.S. source close to the investigation said, “there was evidence that they knew a great deal about the bin Laden organization and about its future plans. That is what really has the FBI fuming.”

‘COMPLICATING FACTOR’

While the FBI fumed, the White House had other plans for Sudan. On Aug. 20, the U.S. fired a Tomahawk missile at a pharmaceutical factory on the outskirts of Khartoum that Washington alleged was producing components for chemical weapons. U.S. missiles also targeted alleged bin Laden guerrilla training camps in Afghanistan on that same day. Sudan denied the charges.

The U.S. insists a soil test outside the plant turned up evidence of a chemical weapons precursor called EMPTA. However, other international experts have continued to raise doubts about the validity of the missile strike.

The U.S. maintains that the plant was a front for a bin Laden associate. Only later did it emerge that the plant produced vaccines on contract for the United Nations.

The missile strike had a predictable effect on Sudan’s covert contacts with the FBI.

After the bombing, on Sept. 2, 1998, the Sudanese deported the two suspects to Pakistan, where Sudanese officials said they were taken into the custody of that country’s security police, the ISI.

While Pakistan, a U.S. ally, presumably interrogated the two men as well, the ISI is not regarded by U.S. intelligence sources as a particularly reliable partner in the fight against bin Laden’s network. As the recent Pakistani-backed incursion into Indian controlled Kashmir demonstrated, the status of Kashmir tops all other interests in Pakistan, especially among the military officials that dominate the ISI.

Several U.S. officials also noted that strong links exists between bin Laden and Pakistani-backed Kashmiri separatists. One official described the ISI’s posture toward bin Laden as a “stew.” The whereabouts of the two suspects remains unknown.

COURTING CONTINUED

Still, despite fierce protests from Sudan over the missile attack, the Sudanese government has continued to court U.S. officials with intelligence allegedly collected during interrogations of the two before they were deported and observations made during the period between their release and their deportation. As late as last month, FBI official had renewed their requests to the State Department to sanction unofficial contacts with Sudan that might lead to new information about the bin Laden network’s plans. Again, the State Department declined.

Several sources close to these incidents said that the dispute has soured relations between the State Department and the FBI division responsible for the bombing investigations.

Another source, a Kenyan diplomat, described his government as “furious” that the U.S. passed up on an opportunity to apprehend men suspected of killing over 200 Kenyans. It was, the diplomat said, “more evidence that 12 Americans count for a lot more than 200 Africans in [the State Department’s] eyes.”

HISTORY OF FRICTION

The bad blood between FBI and State predates the embassy bombings. Over a year before the bombings, Sudan, which has been desperately trying to shed its pariah image in recent years, offered to host an FBI anti-terrorism office on its territory. The proposal, clearly aimed at countering the annual charges that the country aided and abetted terrorists, was contained in a Feb. 2, 1998, cable obtained by MSNBC to David Williams, the FBI agent in charge of the Middle East at the time. Williams, in a letter to the Sudanese four months later, replied, “I am not currently in a position to accept your kind invitation.” The response, sources familiar with the exchange told MSNBC, came after the State Department ruled against the idea. Williams, reached at his FBI office Thursday, declined comment.

The U.S. relationship with Sudan has been a complex and ambiguous one since the ouster of the U.S.-backed military regime of Gen. Gaafar Muhammad al Nimiery in 1985. After a period of anarchy, the current regime seized power in 1989 vowing to turn Sudan into an Islamic state and impose Sharia, the Koranic legal code, on a country that is only about half Muslim.

The rise of the radical Sudanese regime inflamed the country’s civil war, a ruinous affair that has raged for four decades and pitted Christian and traditional factions from the southern part of the country against the Islamic north. The war, which keeps the country perpetually on the verge of famine, has been fueled by U.S. aid to one of the rebel factions, the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army, channeled through Uganda and Eritrea.

International relief agencies in Sudan have been critical of U.S. policy, noting that rebel factions show little more concern for the plight of the civilian population than the government.

Yet the decision to more or less openly support the SPLA has hardened U.S. policymakers on the idea of softening Washington’s stance toward Sudan. The anti-Christian nature of the government’s war against the rebels and highly publicized incidents of slave trading - both by government-supported Islamic militias and rebel factions - has defeated any attempts by Khartoum to win friends in Washington.

John Shattuck, the State Department’s assistant secretary for human rights, told Sudan as much in a June 1998 letter: “We continue to believe that religious persecution on a wide scale occurs in Sudan against Christians, Muslims, animists and others” he wrote to Ambassador Mahdi Ibrahim Mohamed. Shattuck went on to say that the State Department believed reports of slavery were “credible.”

Michael Moran is MSNBC’s International Editor. NBC’s Robert Windrem contributed to this report.

@Copyright MSNBC 1999