In the space of two weeks this spring, economic upheaval in Asia, a political scandal over ties to China and outright nuclear defiance on the Indian subcontinent have dealt staggering blows to the stated foreign policy priorities of the Clinton administration. Any one of these events would be a setback for U.S. foreign policy. But taken together, these developments in Asia have reminded a complacent America that its victory in the Cold War - tremendous as it was - is now ancient history. The politics of Armageddon are back.

WHEN IS THE last time the words “throw weight” was part of a political speech in America?” How about “ICBM,” or more to the point, “MAD - Mutually Assured Destruction?” Ever since Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev uttered the word “glasnost” in 1986, the doctrines and vocabulary of Armageddon - and the weapons that gave rise to it - have been in decline.

Or so you may have thought. For while a handful of think-tank analysts, congressional staffers and arms control activists kept their focus on nuclear issues, the idea of nuclear war - at least the kind that once gave children nightmares during the Cold War - seemed to have been banished from the agenda of mainstream politics and the news media.

The focus of most Western governments, including the Clinton administration, with regard to nuclear weapons during the 1990s has been twofold: the threat of a nuclear weapon falling into the hands of a terrorist or rogue state and the debate over how best to dismantle the huge arsenals amassed by the Soviet Union and United States during their half-century standoff.

In one of his first statements as secretary of state in 1993, Warren Christopher pledged that there would be no higher priority during his tenure than nuclear proliferation. Indeed, efforts were made to ensure that the Soviet arsenal, spread across four former Soviet Republics, wound up in Russian hands with most of it scheduled for (but not yet) elimination. Christopher’s term also saw a highly controversial nuclear pact with North Korea in which Pyongyang traded Western nuclear power-generating technology for a pledge not to develop nuclear weapons.

NEW WORLD DISORDER

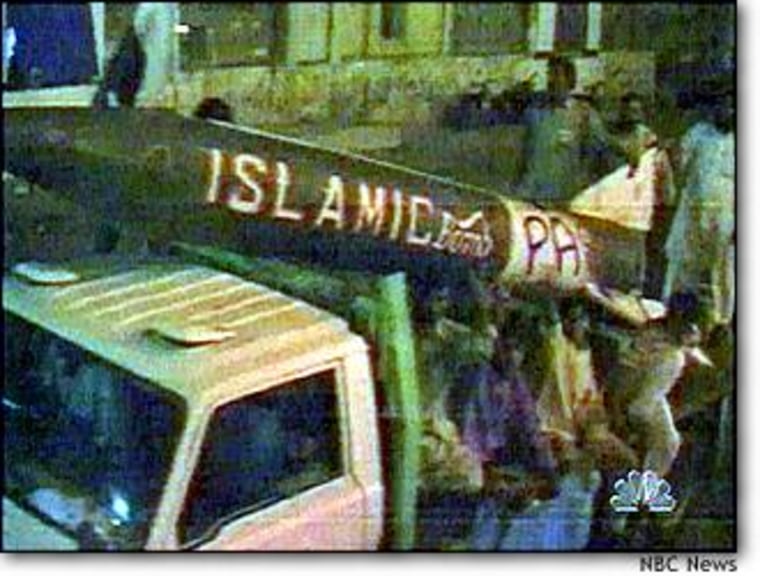

But whatever success the administration might have been able to claim with regard to the former Soviet Union and North Korea was severely compromised this week. Strobe Talbott, a deputy secretary of state and the man dispatched to Pakistan to reason with its government, conceded that the tests were “a setback for the search for peace and stability in the region and ... the global cause of non-proliferation.”

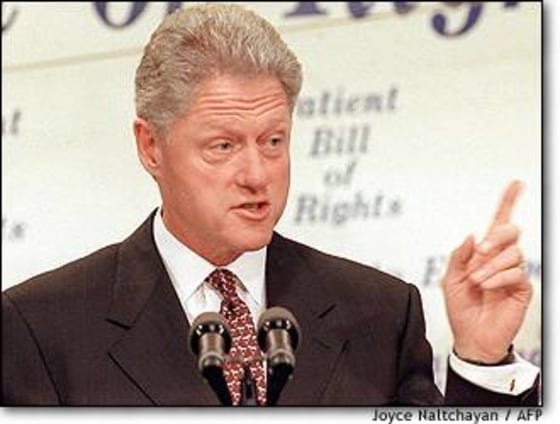

The double nuclear setbacks that confront the Clinton administration right now - three, if you add North Korea’s threat to back out of its 1994 anti-proliferation deal - really don’t fit into any neat category. Clinton was quick to denounce both Pakistan’s and India’s testing. On Thursday, following Pakistan’s tests, he said: “I cannot believe we are about to start the 21st century by having the Indian subcontinent repeat the worst mistakes of the 20th century.”

Yet India appears to have analyzed the costs and benefits of nuclear status somewhat differently. New Delhi apparently felt that established nuclear powers - one of them its bitter rival, China - were intent on ignoring its voice in world affairs.

“The problem is not only Pakistan,” said India’s defense minister, George Fernandes, on Thursday. “We have another neighbor sitting on top of us who has declared weapons.”

Is this proliferation? By U.S. law, certainly, but other nations, including Britain, France and Russia, see Washington’s views as legalistic since everyone has known since India’s 1974 nuclear test that the country has a nuclear capability.

The nuclear testing and the sanctions that followed put an end to whatever hopes still existed in Washington of a new beginning with India, the world’s largest democracy but nonetheless a state that preferred for many complex reasons to trade with the Soviets during the Cold War. U.S. relations with India did actually undergo something of a thaw immediately after the Cold War ended as India’s efforts to slowly open its economy to the outside world coincided with the loss of the close partnership it enjoyed with Moscow.

But the effort stalled, in part because of an aggressive effort by Moscow to hold onto whatever Soviet markets were still up for grabs but also because of a lack of political backing in Washington. From the Indian perspective, as the Clinton administration matured into a second term, it became clear that good ties with China would be the priority in Asia, another blow to what Indians call “a fair hearing” in America. The failure of the United States to better exploit the window of opportunity in India certainly contributed to that country’s decision to defy U.S. wishes on nuclear tests.

ANOTHER SAD TALE

Now Pakistan has followed suit. Again, while U.S. laws clearly deem this proliferation, Pakistan’s capabilities (like those of Israel, for instance) have long been known to Western intelligence agencies and anyone interested in nuclear issues. Once India had thrown off its pretenses, Pakistan’s test probably became unstoppable. As one Pakistani diplomat asked, “Would an American government in the same position have refrained from testing weapons for the sake of a principle like non-proliferation? I doubt it.”

Pakistani officials were furious at Washington following the Indian nuclear tests. Islamabad took to heart the new Indian government’s hints in March that it might exercise “the nuclear option,” a pledge written right into the electoral platform of India’s new ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party or BJP. As recently as November, during a visit to the region by U.N. Ambassador Bill Richardson, the Pakistanis had insisted preparations for such a test in India were under way. If the warnings were taken seriously, it didn’t show on test day. The Indian tests caught both the Clinton administration and the professionals at the CIA and other U.S. intelligence agencies completely off guard.

Clinton and senior officials have expended enormous political capital trying to dissuade Pakistan from responding in kind. Clinton even offered to reverse the effects of 1990 sanctions imposed on Pakistan precisely because of its bomb-making program, the suspended delivery of F-16 fighters, if Pakistan would relent. Unlike India’s tests, though, Thursday’s five blasts probably came as no surprise to the White House.

CHINA CRISIS

Sandwiched between the Indian and Pakistani nuclear tests - which the White House has denounced and reacted to with heavy sanctions - comes the revelation that the White House itself may have sanctioned something that’s closer to the definition of proliferation than anything the Indians or Pakistanis have done.

The longstanding policy of allowing U.S. companies to launch satellites on Chinese rockets was apparently amended by the Clinton administration in a way that permitted - deliberately or not - the transfer of missile guidance technology that may have improved the performance of China’s ICBMs.

The transfer allegedly took place during a review of a failed 1996 Chinese launch in tandem with involving a Hughes Aircraft and Loral of the United States. Adding to an appearance of unbelievable impropriety is the fact that the chairman of Loral was one of the the Democratic Party’s most important donors in the 1996 presidential campaign year. Waivers issued by the administration that favored Loral are now being regarded as highly suspect.

While strictly speaking, this is not nuclear proliferation, the scandal these revelations have ignited will certainly undercut the administration’s ability to take the moral high road with China over its own ample assistance to Pakistan’s nuclear program.

In the long run, it may do deep damage to the administration’s entire policy in Asia - a region the State Department has gone out of its way to emphasize ahead of the millennium. Clinton’s Asia strategy, which is based on the foundation of stable, practical relations with China, will come under enormous fire in the coming months as investigations into the political decisions connected to the satellite launches come to a head.