Back in Campaign 2000, faced with an opponent whose knowledge and experience in foreign policy greatly outstripped his own, George W. Bush made sure he missed no opportunity to sniff at the attention the Clinton-Gore team lavished on U.S.-Russian relations. “Irrelevant,” is how one Bush insider, now a senior Defense Department official, described Russia to me during the campaign. Thank God the president is not too proud to eat those words today.

ILL-CONSIDERED - and sometimes, downright stupid - statements come with the territory during political campaigns (Clinton’s 1992 campaign accusation that Bush’s dad coddled China’s dictators, a charge that came back to haunt him again and again, comes to mind here). Nonetheless, it’s worth reflecting on just how relevant Russia has been to the United States since Sept. 11, 2001.

Since the United States made it clear that it would move against the Taliban and al-Qaida, Russia has been among the most helpful of any foreign nation. President Vladimir Putin, breaking with the political theater that even Boris Yeltsin used to fall back on for domestic reasons, offered no objection to the basing of American troops in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Russian diplomats played important roles encouraging a constructive tone from Iran, urging restraint upon India after Pakistani-backed terrorist attacks. They also have been warning Iraq that Bush appears to mean what he says about “regime change.” Russian troops were deployed to Kabul to help rebuild vital infrastructure; Russian arms and ammunitions were delivered to the Northern Alliance; and Moscow opened a treasure trove of intelligence information on the region to American analysts.

GLOBAL COOPERATION

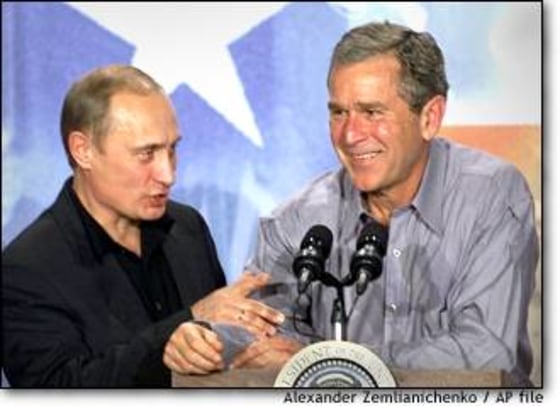

InsertArt(1913386)The bigger picture has been even more important as Russia has started cutting pragmatic deals with the United States on major issues. Russia acceded to the deployment of American forces to the republic of Georgia, where some al-Qaida remnants appear to be operating. It dropped its objections to American proposals that reform the U.N. sanctions against Iraq, a key part of the Bush administration’s plan to pressure (or eventually, to force) Iraq into compliance with the Gulf War cease-fire accords. The rhetorical defenses of the old regime in Serbia - popular in some quarters in Russia as a sop to “pan-Slavic brotherhood” - have all but disappeared.

And then came last week’s nuclear arms control accord, the clearest indication yet that Russia has decided it has more important battles to fight than its nostalgic ideological rivalry with the United States. The accord means the U.S. decision to abrogate the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty will not be seized upon by Putin as a way of mollifying his own right-wingers. Instead, Putin appears to have settled for a far more beneficial trade: a voice in what NATO does on a new NATO-Russia council, plus compromises on the terms of the missile deal that will allow Russia the flexibility to remain a superpower - at least in terms of nuclear throw weight - even while its economic and diplomatic muscle shrinks to the bantamweight division.

The key to the deal is an American concession that limits the number of warheads - instead of the number of missiles - each side can hold to 2,200 after the year 2012. On top of that, warheads not sitting atop deployed missiles will not be counted. While that certainly degrades the deal in terms of its stringency, it also allows Moscow to maintain a credible deterrent to the U.S. arsenal, a key issue from the Russian perspective. In fact, with 2,200 warheads, Russia will be assured of the ability to overwhelm any American missile shield that could possibly constructed in the near future, experts on both sides say.

The fact that the Bush administration conceded these points also shows it means at least some of what it says about the missile shield: that it is not aimed at Russia, but rather at “rogue” missile states.

LEARNING THE ROPES

Slowly, the old hawks that run the Bush team seem to be learning that there is little mileage left in gloating over America’s Cold War victory. The stand-off between the United States and Russia never involved either one lusting for the other’s territory. It was an ideological battle that ended with a crash when the Berlin Wall fell. Maintaining the extensive doomsday infrastructure built to deter Soviet Russian missiles is, for all intents and purposes, idiocy in the modern world. Like Moscow itself, Washington now has other, far more elusive fish to fry.

Now, instead of sneering at Russian objections, the administration appears to be adopting the far more realistic position of humoring Russia’s delusions of superpower status. Along those lines, the United States, wisely ignored Israeli objections recently and accorded Russia full “co-host” status in the upcoming Middle East peace conference, along with America, the European Union and the Arab League. If that’s what it takes to win cooperation on truly important issues - like sanctions against Iraq or the war on terrorism, then bravo.

A BRIGHTER FUTURE

Behind all of this incremental progress is an even more tantalizing strategic agenda: a fuller integration of Russia into the club of Western democracies, and a shift by Europe and the United States from dependence on Arab oil to Russian oil and natural gas.

On the first count, there is much work to do, and this time it is primarily on Russia’s side. Despite progress - quite amazing progress, when you consider where Russia was only a few years ago - democracy is still spotty, and large problems still impede the move toward free enterprise, especially outside the big cities of western Russia.

The war in Chechnya, a brutal affair studded by abuses by both sides, shows that Moscow continues to view Western standards of human rights as an optional affair when the going gets tough. That has to change.

On the oil front, there is a revival of a term from the 1990s: synergy. With the oil-producing Arab states still unreformed dictatorships (and thus, by definition, unreliable allies), America is looking for other ways to meet its huge demand. Russia, alone among the world’s non-OPEC producers, has the excess reserves - though not the capital to exploit its capacity.

Increasingly, there appears to be a dialogue that envisions a future where oil from Russia begins to displace Arab oil. Displacing it altogether is probably impossible - and in any case, it isn’t in the West’s interest to deprive the Arab world of all revenues. But removing “the oil weapon” from the hands of despots can only be a good thing. The key now is to ensure that Putin, the man Bush appears so at ease with, doesn’t turn out to be one himself.

Mail your thoughts to Michael Moran, request to join (or be removed from) his email notification list.