The year is 1912, and a shadowy, loosely networked movement devoted to the violent overthrow of the West plagues the earth. Since 1894, its bombs have rocked opera houses and courtrooms; its gunmen claimed the lives of the empress of Austria-Hungary, a Russian czar, the king of Italy, the leaders of France and Spain (twice) and U.S. President William McKinley, and left a bullet in the chest of another president, Teddy Roosevelt. All these attacks, the perpetrators hope, will spark a revolution of the poor that would sweep away the West’s ruling class.

In fact, it was World War I and not the assassins and bomb-throwers of the Anarchist movement that would change the course of Western history. The Anarchists were dangerous, to be sure. And their cousins, the Communists, turned out to be one of the 20th century’s great curses. But in the years prior to the First World War, governments in Europe and America were obsessed with the Anarchist danger, and this fostered a paranoia that obscured the far more dangerous clouds gathering over the West: the flawed system of international treaties that would plunge the planet into its bloodiest conflict, up to that date.

Instead, witch hunts were pursued by democracies and monarchies alike. Civil rights were trampled. Summary executions were ordered in Spain. Devil’s Island filled with French pamphleteers. And in the United States, this atmosphere led to the most notorious miscarriages of justice in American history — the trial and execution of two Italian immigrants who held anarchist views, Sacco and Vanzetti.

DEJA VU?

By now, I have lost anyone whose idea of history is a documentary on the evolution of dancewear. So be it: such people are doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past. May they wear their unitards in good health.

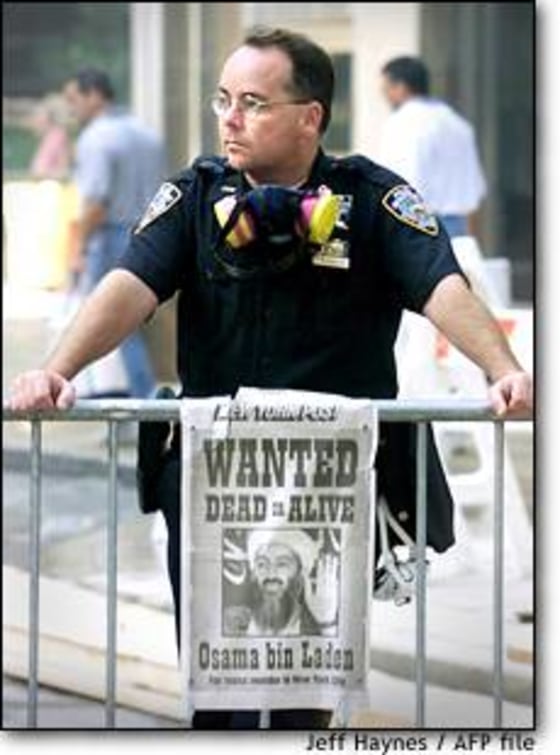

The rest of us - the thinking, reading, unitard-averse American public - should be skeptical of the black-and-white version of the world being marketed by the White House right now. Al-Qaida is evil: yes, we get that. It may stop at nothing to kill more Americans. But it is not all-powerful and it should not make Americans quake in their boots. Unfortunately, the tone of the American government’s response gives too much credit to this group of misfit misanthropes from the Middle Eastern middle class. As if bin Laden himself wrote the script, we have accorded al-Qaida equal status with what was once known as “the communist threat.”

Is al-Qaida the Anarchist movement of the early 21st century, destined to burn furiously before collapsing in on itself, discredited, defeated and far less clever than anyone gave them credit for? I believe that is the reality — and reality, not panic, is the rock upon which foreign policy should be based.

BEFORE YOU SHOOT

“What?” you ask. “How can this guy downplay the threat of al-Qaida?”

That is not at all what I’m doing. I don’t normally quote myself, but in this case, I’ll make an exception. Back in 1999, after an alleged al-Qaida plot to disrupt the millennium celebrations in America, I asked why the United States would continue to permit the existence of a regime (the Taliban) that was sheltering a group (al-Qaida) that clearly was plotting a cataclysmic attack on a major American city.

“If there is real evidence that bombers trained and succored in Afghanistan are planning to strike at U.S. cities, the question changes. The West, which fought a war to rescue Kuwait from Saddam Hussein and Kosovo Muslims from Slobodan Milosevic, has made surprisingly little of a threat to its own populations. Some are asking precisely what order of atrocity will it take for these great powers to put aside their differences and act together against the Taliban and the threat it nurtures. Would the destruction of the Seattle Space Needle have been enough? It’s hard to say.”

Thus spake me. So, you see, I am not bent on downplaying our response to al-Qaida; far from it. Show no mercy, I say. But in pursuing them, I think it is worth wondering if America is missing the forest as it uproots the trees.

LIFE’S NOT A BOX OF CHOCOLATES

The black-and-white rhetoric of the war on terrorism is not serving the longer-term interest of the United States. Briefly defined, that interest is in creating a world where threats against any nation can be met and deterred before the first blow is struck, not after a portion of a city has been turned into cinder.

This is precisely the opposite of where the Bush administration is leading us. Eggs must be broken to make a cake, to be sure, and no objection to our pursuit of bin Laden into Afghanistan or even Pakistan should have been taken seriously. Yet while American military forces rightly ferret out the enemy, American diplomacy is dismantling the fragile post-Cold War consensus that was the one great hope of preventing future basketcase nations like Afghanistan from turning into a growth medium for terrorism.

WHY LIMIT YOUR ARGUMENTS?

The ability to intervene in the affairs of a foreign country — be it Iraq, Somalia, Bosnia, Haiti, Kosovo or Afghanistan — was not invented by the United Nations as a plot to drain foreign aid and soldiers from America. In fact, during the Cold War, with very few exceptions, political realities and the way the U.N. Charter was drawn up made it virtually impossible to legally mount the kinds of interventions that ended hunger in Somalia (briefly), slaughter in Bosnia and Kosovo (belatedly), dictatorship in Haiti (arguably) and the Taliban’s hold on Afghanistan.

As Bill Emmott, editor of The Economist, noted recently, other countries spent much of the 1990s trying to persuade the United States to live up to its “obligation” as “leader of the free world” to intervene in such places. Over the course of the decade, the abuse of one’s citizens began to win acceptance as a legitimate reason for intervening, and in the Balkans and in East Timor that principle was tested and proven sound.

If you don’t like the list of “successes,” consider the places where America chose not to go the extra mile. In Iraq in 1991, cynicism prevailed in Washington and Saddam haunts us to this day. In Rwanda in 1994, the world turned its back on genocide and war rages there still. And we all now know the price of abandoning Afghanistan to its fate once the Soviet army left in 1989: the rule of fanatics, a generation of warfare, the collapse of civil authority and ultimately, Sept. 11.

MAKING FRIENDS, INFLUENCING PEOPLE

Viewed from this perspective, it should be clear how the victory over al-Qaida in Afghanistan could backfire. The Bush administration, from its snubbing of NATO and India to its mishandling of Iran and the Middle East conflict, has given the rest of the planet the impression that no other nation, friend or foe, has an opinion worth even considering when it comes to America’s pursuit of al-Qaida.

In doing that, the administration has squandered the sympathy of the world for the Sept. 11 attacks. Worse still, it threatens to abolish the precedent set since the Berlin Wall fell for precisely the kind of bold action that is needed to prevent states from becoming Fanatistans. The distrust sown by this administration risks turning back the clock to a time when “moral” or “humanitarian” interventions were viewed so subjectively that they simply were not possible.

A LIGHT BULB IN THE WHITE HOUSE

The limitations of the “go it alone” approach are quickly being realized, and there are signs the Bush administration is backpedaling. On foreign aid, the administration announced a 50 percent increase at a recent summit in Mexico, a huge turnaround for a Republican administration and an important step in battling those who see the U.S. as turning its nose up at the causes of terrorism.

This week, the United States abandoned its diplomatic tantrum over the troublesome structure of the new International Criminal Court, after earlier putting itself in a situation in which it threatened, in essence, to veto all U.N. peacekeeping operations.

Oversimplifying the challenges facing the United States has made “homefront security” an easier sell, for sure. This stems from a sense that Americans don’t really understand the world well enough to hear the details, which in turn explains why big policy speeches in this administration often recall bedtime readings of “Clifford the Big Red Dog.”

In the long run, however, this approach is callow and calculating. It was the same lack of context that left America with its pants - and Air National Guard units - down on Sept. 11.

These things are not at all obvious to those whose interest in foreign policy began on Sept. 11. It would seem quite reasonable to Mr. and Mrs. Internet Bubble Economy that American foreign policy be single-mindedly dedicated to the destruction of al-Qaida, and that no opinion from filthy foreigners be taken into account.

Yet, 20 years from now, the piper will want to be paid. What’s likely to be more important to American interests then — a desperate band of terrorists marked for destruction, or the rise of China in Asia? Do we really want to undermine international institutions and laws to the point where the only incentive for “good behavior” is the threat of American troops?

America’s desire to pursue al-Qaida around the globe is correct and it is important. But it does not require the alienation of friends and enemies alike, the splitting of the planet into two rival camps, the destruction of institutions like the United Nations, or big signs on who is “evil” and who is not. Quite the contrary: when the last al-Qaida operative is dead and buried, America’s place will be measured in how much of the big picture was kept in focus as we rooted through caves in Central Asia searching for the tiny group of monsters that started it all.

Mail your thoughts to Michael Moran, request to join (or be removed from) his email notification list.