No map of the world that does not contain Utopia is worth having, Oscar Wilde famously said, and by and large Americans agree. We tinker with every aspect of our society, whether it is the Supreme Court striking down a flawed legal precedent or baseball realigning its divisions. The incremental nature of the changes we make, even in the face of outrages like segregation or Watergate, are a vote of confidence in the fundamentals of our society. But will incremental change fix what’s wrong with American capitalism? After all, great empires fall not because of attacks from the outside, but rot from within.

BEHIND AMERICA’S restless incrementalism is a healthy, communal recognition of humans as flawed, and — except for some nutty fundamentalists who take every word in the Bible or the Constitution literally — of the need to fix things when it becomes clear they are broken. Last year, a hateful band of fundamentalists of another stripe demonstrated that our intelligence and national defenses were broken, and with all the clamor and angst befitting a great nation, the United States has set about fixing the invisible shield we somehow thought protected our Utopia from such attacks.

This is a work in progress, and like human beings, the fixes themselves will be flawed. Some will go too far, eroding the very freedoms that spark the fundamentalists’ resentment. Some will fall short, unable to surmount the entrenched bureaucratic and political interests that protect places like the CIA and the Pentagon from the kind of scrutiny the average person is subjected to by the IRS.

The dilemma here is that “national security,” while abused as an excuse to hide things from the public, is a very real issue, as well. A very strong argument can be made for completely reorganizing America’s intelligence agencies, for instance. An equally strong argument can be made that the distractions and displacement involved in such an enterprise would produce, temporarily at least, exactly the kind of blind spot our enemies seek to exploit. Incrementalism, for now, appears to be the only way forward in the defense and intelligence realm if we are to secure our democracy without leaving it open to attack.

APPLES AND ORANGES

This is not true for corporate America, however. Here, the pendulum of regulation vs. deregulation has spent so much time on the deregulatory side that executives and their political poodles in Washington (in both parties) had forgotten it existed. After two decades of deregulation of their affairs, beginning in 1980, and a decade of hucksterism (aided by a less-than-skeptical media), corporations have no fig leaf to hide what they have done. Some in the corporate world are direly warning that any severe move to restrict their ability to cook the books — ideas like treating stock options as an expense, for instance — will risk throwing the economy into a tailspin.

A good example of this is this bit of psychotherapy offered by columnist Holman W. Jenkins Jr., to the poor, misunderstood executives of America on today’s Wall Street Journal editorial page:

“We’re not even sure the incidence of corporate scandal is any higher than normal - i.e., that a ‘crisis of confidence’ was ever particularly warranted.”

Warranted or not, apparently corporate America has lost the nation’s confidence.

That this would strike anyone, even a Wall Street Journal columnist, as surprising defies credulity.

Even among staunchly pro-business Republicans of the House of Representatives, there are some who are seeking religion on this issue. Urging his House colleagues on Monday to adopt the Senate’s tougher version of corporate-reform legislation despite its Democratic origins, Louisiana Republican Billy Tauzin said: “There are not enough differences [of opinion] that we ought to risk a conference on this bill in this environment.” Coming from the chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee — one of the great political money troths in all of American politics — that is a powerful statement.

Another Republican, Mark Foley of Florida, said: “It’s time we stop playing politics and work together toward a common goal.”

That statement may reflect less of their actual opinion than their upcoming need to stand, straight-faced, in front of voters and request re-election. If so, democracy in Florida is in better shape than I thought.

DICTATORSHIP OF THE SHAREHOLDER

The idea that corporate lobbyists would argue that such reforms should not be held hostage to the whims of the angry mob is particularly galling considering the pandering (and damage) America’s executives do on behalf of that ultimate constituency, “the shareholder.” What angrier mob is there in America right now, after all, than any of us who staked our retirement on the stock market?

In the name of stock values, a publicly traded company, it seems, can rationalize away almost anything for short-term gain.

How about we pretend to have billions of dollars in profits that we actually pissed away in the last quarter? Just do what WorldCom did, and move those billions from “expenditures” to “assets.” But make sure you get your money out before the suckers figure it out.

Need a quick way to shore up that sagging share price? Encourage your employees to buy more stock options, even as you unload yours before the house of cards tumbles down.

The great part here is that even your accountants won’t bust you. Remember in the 1980s, when Brazil owed so much money to Citibank and other lenders that it could dictate terms to them? Well, there’s a similar dynamic here: Get the accountants in so deep that they wouldn’t dare blow the whistle. If Enron could do it, why not us?

WHAT’S AT STAKE

“Business is the business of America.” This was the most memorable phrase ever uttered by the otherwise forgettable President Calvin Coolidge in the pre-crash 1920s. The results of this approach to economics became clear in 1929, when the under-regulated and thoroughly corrupt edifice of American capitalism came crashing down.

It would be wrong to say that the current corporate scandals put American capitalism, or America’s place in the world, at stake. Through crisis and war, success and failure, the United States’ lead on other nations has done nothing but grow in the past 40 years.

But that is partly because, when rot is detected, it is treated seriously. From confronting communism to investigating Watergate, from neutralizing OPEC to the swamp of Whitewater, Americans don’t shrink from scandal for the sake of sparing the economy or national pride. It hurts in the short run, and may not always result in short-term justice. But our intolerance of rot pays off over time. The same intolerance should be applied to corporate fraud.

The forces at work in 1929 and now have virtually nothing in common. One exception: corruption. The lack of controls on how stocks were traded early in this century created fortunes for a small and ruthless few — most famous of them, Joseph Kennedy. As today, when things went south, most of these fellows got out early, or at least early enough to avoid selling apples on Chambers Street. It was the rest of the country — the workers laid off from bankrupt firms, the small investors who trusted their savings to these crooks, who wound up in the gutter.

Since 1929, the American economy has matured to the point where market drops - even crashes, as in 1987 - do not necessarily create catastrophe on a wide scale. The Securities and Exchange Commission polices stock trading now, and a host of other oversight is supposed to ensure that money made on Wall Street was made honestly and that the value of the stocks listed there had some grounding in accountancy (even if marketing and group psychology inflated them beyond recognition).

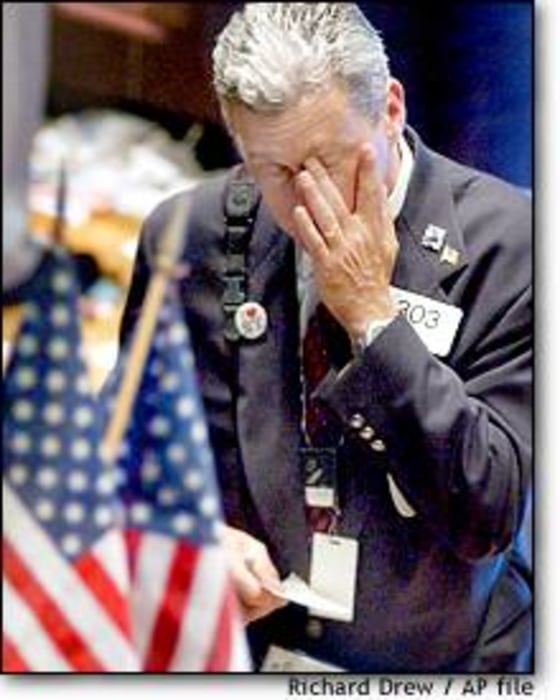

Not many Americans would include “accurate accounting” in their definition of Utopia. Indeed, most people don’t even realize that every bitter complaint they voice about politicians or the media or the IRS at a backyard picnic, and every decision they make on their means of saving for retirement, is really a shot fired for that personal Utopia. Withdrawing money from the stock market is another shot — this time, across the bows of Wall Street and the corporations listed there. “The fix is in,” people are saying, “we get that.” The market, so to speak, has spoken. Even the president sounded a bit like Ralph Nader last week. How long before corporate America notices the rot, too?

Mail your thoughts to Michael Moran, request to join (or be removed from) his e-mail notification list.