One of the most remarkable achievements of this final and remarkable decade of the 20th century passed almost unnoticed as the American media hyperventilated over a stained dress. South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission took much of what cynics believe about the world and stood it on its head. It forgave the unforgivable, gave vent to the thirst for vengeance, threw light into areas meant to be left in darkness.

WHETHER THE WORK of the TRC leads to racial harmony in South Africa is beside the point, for it has averted the civil war that nearly everyone viewed as inevitable as apartheid entered into its death throes. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which wrapped up its work in late July, succeeded by becoming the exorcist of fears built up over generations by offering not revenge, but truth; not “justice,” but amnesty. Its final report is yet to be delivered and hundreds of outstanding claims for amnesty are still to be processed. South Africa could yet destroy its achievement if a post-Mandela government chose to pursue vengeance. A short peek at is enough to leave anyone who has ever covered the end of a conflict in awe.

NO PAIN, NO GAIN

Of course, there is no guarantee that South Africa will overcome the legacy of racial intolerance that defined it for so much of this century. Indeed, already there are signs in the post-apartheid country of a “separate-but-equal” movement among whites, many of whom have fled once segregated

Johannesburg and other large cities for the lily-pure whiteness of new suburban areas. Is this the “new South Africa” Mandela envisions? Not likely. But then, as we high and mighty Americans have learned, you can’t legislate integration, only provide incentives.

Still other South Africans have fled for Britain, Australia, Canada. Many tell tales of a crime wave (though crime rates are far higher in U.S. cities) and speak in apocalyptic terms about what is still to come. Further down the food chain are the genuine fascists produced by a half-century of apartheid. I met a trio of these fellows in Croatia in 1993 who had found employment teaching “point-to-point” infantry tactics to Zagreb’s new army. They bragged of cutting throats and booby-trapping “Chetnik” villages, as the Serbs were derogatorily known. I must admit the thought of this crew granted “amnesty” makes me question the methods of the TRC.

Yet as a model for confronting the causes of racism — rather than the crimes that are its symptom — the TRC has proven itself. In the charged atmosphere of 1993, when suddenly South Africa’s whites woke up to the true meaning of democracy, any attempt at Nuremberg-style justice would have sparked a civil war and likely destroyed another generation, not to mention the country’s economy. Mandela saw that and prevailed over hotter heads in the victorious anti-apartheid movement, probably saving tens of thousands of lives.

ULTERIOR MOTIVES

Mandela’s way was always destined to be a controversial one and there are those in both the black and white communities who disdain the process. The more radical wings of the African National Congress clearly feel that show trials followed by executions would have been preferable. Many whites fear these forces are biding their time for a post-Mandela era.

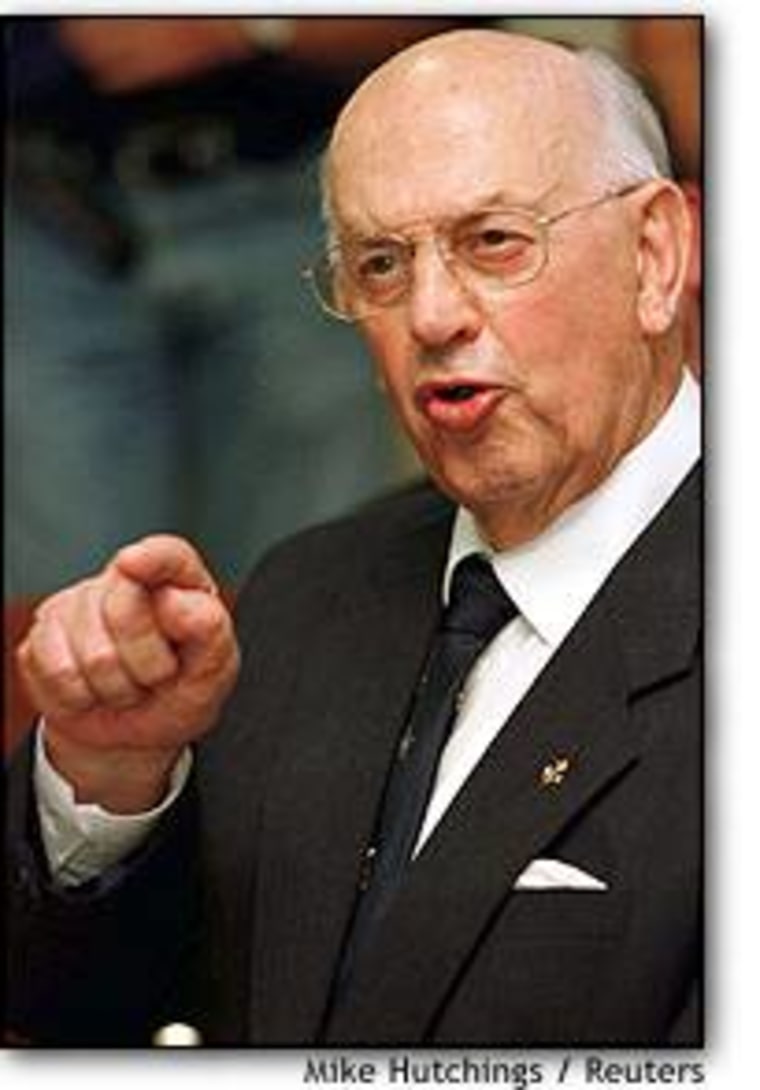

On the other side of the spectrum, former Prime Minister P.W. Botha, perhaps the most prominent living criminal of the apartheid era, refused to give evidence despite the fact that he might have avoided prosecution as result. Typically, faced with a generosity of spirit he could not digest, he tried to undermine the very body that was preventing his lynching. The idea of the aptly named “Big Croc” being offered anything but deference by a black man was clearly too much to ask.

But the desire for “amnesty” — and who knows, maybe even an element of guilt — led plenty of the “Big Croc’s” underlings to testify.

The accounts of murder and mayhem delivered by the culprits themselves at first held South Africa spellbound — the murder of activist Stephen Biko, the murderous thuggery of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s coterie, the torture and terrorism practiced by South African security forces, the mindless murder of a white American student by the the very blacks she had come to help.

As the hearings wore on, the morbid curiosity dimmed for all but a small number, according to South African polls. The process became numbingly dismal for all sides, a sign that the catharsis was working. Whites tired of it because it emphasized the tyranny through which they prospered; blacks, because it seemed almost unbelievable that a public mea culpa on the part of apartheid figures could buy them amnesty. And victims of all races struggled to accept it because forgiveness is often more than a human being can bear.

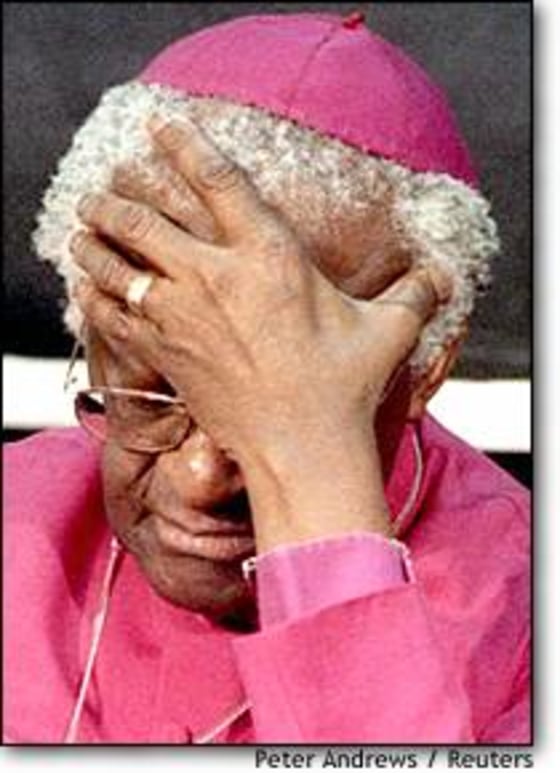

Yet bear it they have, for the most part. No, South Africa is no racial paradise and it is worth pointing out that neither is any other country on this planet. But this deeply flawed state has over the space of two years given itself a chance, as Archbishop Desmond Tutu put it, to “shut the door on the past and now move forward together.”

Amen, Archbishop. Amen.