Neither the barnacle-encrusted Russian Black Sea Fleet nor the angry cries of “imperialism” from China’s Foreign Ministry will alter NATO’s war plans in Yugoslavia. But both nations do have the power to disrupt Western interests as the new century dawns. What’s more, the war in Kosovo may just prove to be a turning point in post-Cold War geopolitics. Whatever motives Washington and its allies ascribe to this war, Moscow and Beijing see the conflict as a stark demonstration of how little they figure in America’s current global game plan.

FOR THE short term, none of this has anything to do with military force, let alone nuclear weapons. Rather, it is about the mischief these two powers could potentially make through arms and technology sales to U.S. rivals, by embargo-busting trade deals and “reaching out” to old friends like Cuba, Syria, Libya and Latin American guerrillas. Add two vetoes on the U.N. Security Council, and suddenly Pax Americana has a problem.

The greater fear, one being officially dismissed but privately nurtured in Washington and other NATO capitals, is that NATO’s decision to take unilateral action against Yugoslavia has transformed it in the eyes of Moscow, Beijing and other non-NATO powers from a defensive alliance into an avenging, crusading tool of American foreign policy.

DIMINISHING RETURNS

What’s wrong with that? I hear half my readers asking (with the other half muttering, “paranoia.”) Whatever side you come down on, it is foolhardy to believe that the transitional period we have been living in since 1989 can continue much longer.

There is a law of diminishing returns — an economic concept that even China’s communists and Russia’s oligarchs recognize.

Briefly stated, it goes something like this: Co-operation with the United States is in our interest as long as we profit economically more than we suffer in loss of power and prestige. Put another way: Both Russia and China have been willing to chuck ideology and curb arms sales to rogue regimes in exchange for membership in the “club of prosperity” the United States presides over. Russia now knows it’s unlikely to get past the bouncers. And China, whose Prime Minister Zhu Rongji arrives in war-gripped Washington on Wednesday, will get the same message this week.

TOO LITTLE TO LATE, OR INEVITABLE?

Token efforts were made in this decade by the U.S. and the European Union to ensure that Russia would develop democratically and feel its interests and those of the West were indistinguishable. Certainly, enormous effort has gone into wooing China into accepting Western democratic standards.

At the end of the day, however, both of these undertakings have been failures. Russia is on the verge of a new round of elections to be conducted in an atmosphere of abject humiliation. Its currency is worthless, its politicians powerless and its word abroad meaningless. Not exactly fertile ground for democracy.

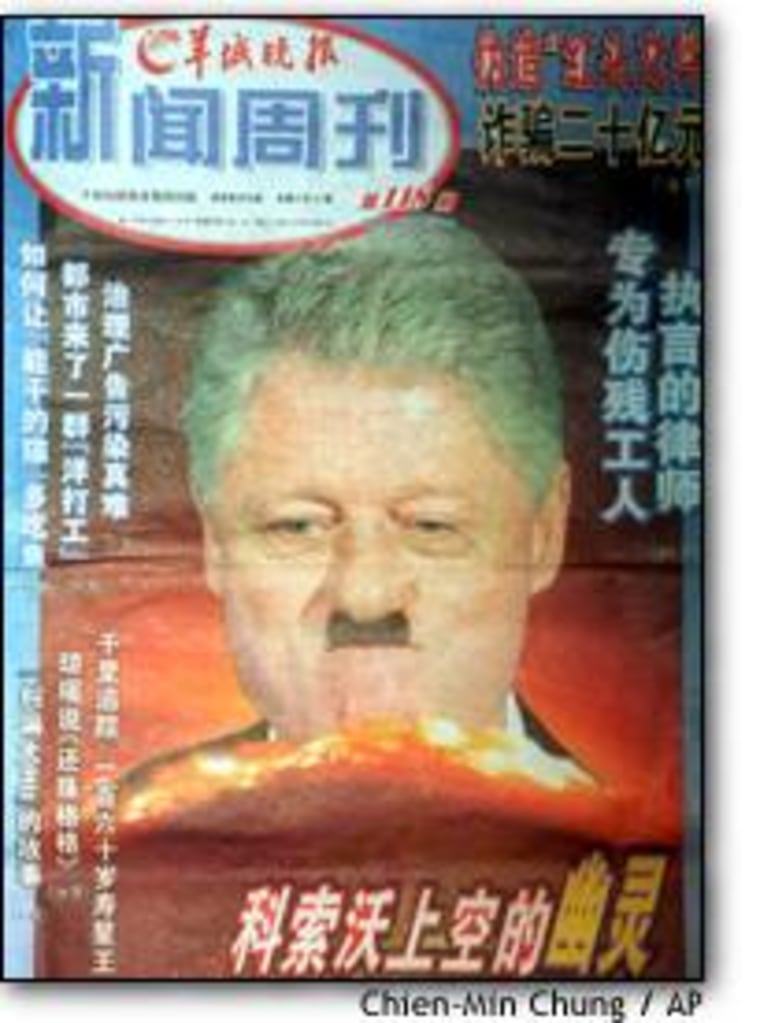

China, on the other hand, has betrayed those in the U.S. who staked their names on Beijing’s development along more democratic lines. It has become clear to most who care about such things in the U.S. that China’s current leadership has no intention of allowing criticism to take the form of a challenge to communist domination of the state. It has become more and more difficult to argue that China is doing anything but soaking as much technology and investment as possible from the West while pursuing a long-term policy that puts these “trade partners” in direct conflict.

BACK TO THE FUTURE?

In both cases, of course — in Russia and in China — some monumental act of people power could produce some utopian result. But it appears just as likely that both countries, feeling increasingly threatened by the West’s willingness to intervene in the affairs of other sovereign countries, will begin to patch up their own relationship.

The rift should not be underestimated. Since Stalin’s death in 1953 and especially since 1959, when Moscow recalled “advisers” from China, relations between Moscow and Beijing have often been worse than those between the U.S. and either of them. In 1969, Chinese and Soviet troops fought a pitched battle over their long Far Eastern border — a rift Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon eventually exploited to sow the seeds for the current U.S.-China relationship.

Since the Soviet Union’s collapse, there have been several high-profile attempts to patch up relations, including a co-operation pact signed by the two countries in 1997. The reality, however, is that they do not trust each other. The Russian nuclear missiles “detargeted” from American cities in the early 1990s were set instead on China.

Increasingly, though, these two find themselves to be “outsiders” with a lot in common. Both have been left out of the planet’s most important financial clubs, the Russians by default and the Chinese by falling short. Both, too, face a world in which their great traditional economic strengths — their huge populations and their great land masses — are rendered irrelevant or even as disadvantages by Western technology they have to steal or cannot afford to buy en masse.

Most importantly, though, both in China and in Russia, it will be easy for politicians seeking domestic support to blame their suffering and national setbacks on the United States.

Neither Washington nor its allies would ever contemplate a Kosovo-style intervention in Tibet or, say, Chechnya, where human rights violations on a massive scale certainly exist. But that won’t matter in China or Russia. A justifiable intervention to stop ethnic Albanians from being slaughtered in Kosovo has set a precedent that can and will be twisted to whip up fears of a similar move against Russian or Chinese territory. Already, Russian right-wing and communist politicians eyeing this December’s parliamentary elections are making the point. Kosovo, then, is more than a NATO war to stop Yugoslav ethnic cleansing. It is a declaration of war against oppression everywhere and, even for the world’s only superpower, that’s an awesome burden to assume.

Michael Moran is MSNBC’s International Editor