In a painful reminder of the burdens of free government, the United States once again finds itself outmaneuvered by Iraq’s dictatorial leader, Saddam Hussein. Indeed, in the past month, three despots have exploited the greatest vulnerability of the world’s sole remaining superpower: its soft underbelly of decency.

THE METHODS vary but the tactic is the same: provoke, bluff your quarry to the brink and then at the last minute, fall back and laugh in the face of the helpless giant.

Choose a despot: Iraq’s Saddam Hussein. Yugoslavia’s President Slobodan Milosevic. North Korea’s President Kim Jong Il. All three flashed their red capes before the American bull in the past few weeks and, despite a lot of snorting and hoof play on the part of the bull, all three emerged unscathed.

Dictators, of course, have the advantage of being able to write their own rules. It’s hardly a new phenomenon. In 1938, Winston Churchill denounced then-Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain for appeasing Hitler rather than going to war over Germany’s annexation of Czechoslovakia. “The German dictator, instead of snatching the victuals from the table, has been content to have them served to him course by course,” Churchill told parliament.

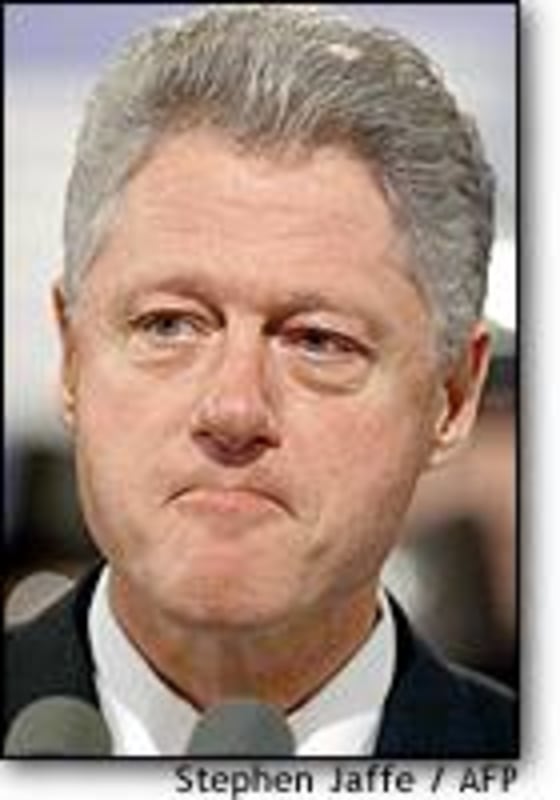

Clinton is hardly an appeaser. But the past month suggests that his enemies may have him figured out.

ONCE FOOLED, SHAME ON YOU ...

In late October, U.S. forces in Europe stood poised to strike at Serbia over that country’s attacks on civilians in its Kosovo province. NATO demanded that Milosevic pull his security forces out of the province and open talks with the ethnic Albanian separatists who form the region’s overwhelming majority. Milosevic blatantly ignored the first deadline for air strikes. NATO, fearful of civilian casualties, granted an extension. Serb forces pulled back slowly after signing an agreement with the United States. Since then, however, it has rejected a U.S. plan to grant autonomy to the Albanians under Serbia’s sovereignty. Talks continue, but the rebels and Serb forces are fighting once again.

By November, the scene had shifted to the Persian Gulf, where yet again American naval and air forces readied to bomb Iraq into complying with U.N. Security Council resolutions. Iraq cut off cooperation with UNSCOM, the U.N. special commission charged with enforcing the Gulf War cease-fire’s disarmament provisions. Despite an open- ended threat of U.S. force and little support for Iraq in the usual quarters, Baghdad refused to back down. Only at the last possible moment, with some U.S. aircraft literally in flight, did Iraq make its move. In a series of letters that followed, Iraq agreed to an unconditional resumption of UNSCOM inspections that left the United States in a terrible dilemma. Air strikes were cancelled. Within days, Iraq rejected a request from UNSCOM for arms-related documents and yet another standoff appears to be building.

Hardly a day after the Iraq crisis returned to its dormant stage, the United States was exchanging angry words with North Korea and threatening to cancel the nuclear accord that averted a shooting war there in 1994. The United States, citing satellite evidence, suspects the North Koreans of working on an underground nuclear weapons research facility. If true, it’s a blatant violation of the accord by which the famine-wracked North agreed to halt nuclear weapons research in exchange for western nuclear power technology, food and oil to tide them over in the meantime. The North has rejected U.S. demands for an inspection of the site unless it gets $300 million up front as a kind of “access charge.” The United States appears angry enough to argue, but not to break off the agreement.

DESPOTS: 3, AMERICA: 0

Three crises, three similar outcomes. How can it happen?

In touchy diplomatic conflicts like the ones the United States has faced recently, American policy appears to have been foiled by a mix of philosophy, physics and psychology.

Philosophically, there is no more difficult enemy for the leader of a wealthy democracy to face than the dictator of a miserably poor, isolated nation. Dictators know the rules an American president must play by and the higher standards they have to meet.

This is an important part of the calculus of the endgame in these standoffs. The idea that Saddam, for instance, loses face by retreating is based on the incorrect assumption that someone inside the country would survive criticizing him. Saddam can demand the world and accept nothing and still come out on top, assured his every move will be applauded by anyone within pistol range of his regime.

Physics, too, is on the dictator’s side.

Time, for instance, is measured far differently by “Great Leaders” and “Presidents-for-life” than it is by lame ducks. The Yugoslav, Iraqi and North Korean conflicts vexed President Bush and were passed on to Clinton. Who in 1991 would have deemed Saddam the Gulf War’s victor?

As time passes, the case for Saddam looks better and better. It’s quite likely the next American president will curse the inheritance as well. The mistake democracies make is equating a country’s plight — the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the destitution in Iraq, North Korea or even Cuba — with the leader’s standing. The dictator believes the people exist to serve him.

The cost of a conflict, whether measured in human lives, dollars or lost national potential, is another area in which the dictator has the upper hand. Certainly, none of America’s current rivals threaten the nation in the conventional sense. How else could North Korea dare to test- launch a ballistic missile in a period when international aid groups say up to 3 million of its citizens have perished from malnutrition? Clinton, on the other hand, must weather constant second-guessing: spreading thin the U.S. military (Bosnia); squandering U.S. “credibility” (Iraq); appeasing its enemies (North Korea).

Thus to psychology. Here the wealthy democracy should carry the day. Behind each side’s brinkmanship there are a complex calculations going on about just how far the other side is willing to go. In the United States, this is the realm of intelligence meant to penetrate closed societies. Are air defense units on alert yet? Is there hoarding of vital supplies? Is the leadership dispersing?

One can only imagine the scene on the other side. Some genuine intelligence — eavesdropping and espionage — would be involved. Endless and somewhat overblown analysis of U.S. media would also play a part. Tips from sympathetic third parties might also be involved.

But in the end, the psychological game — indeed the fate of the nation — depends on the instincts of the two leaders. Know thy neighbor, Mr. Clinton. The past month suggests they certainly know you.

MSNBC’s international editor, Michael Moran, writes a weekly column on foreign affairs.