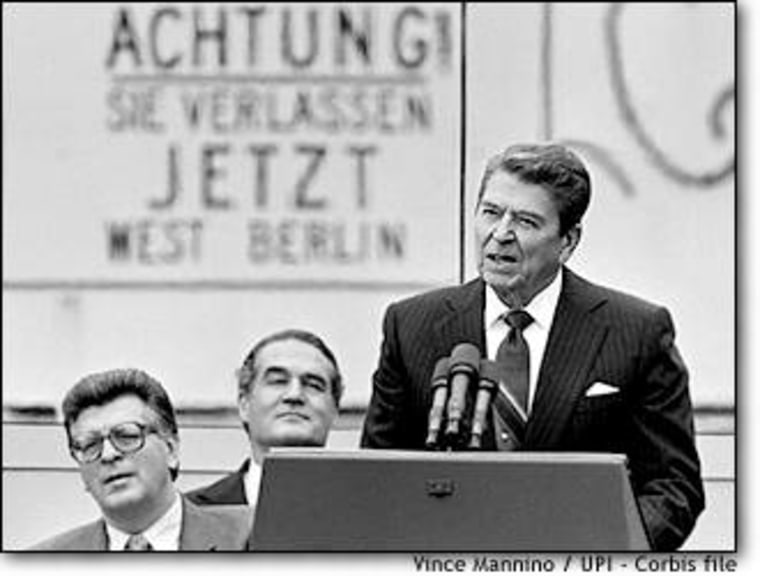

The Clinton administration’s China policy, six years old and desperately short on success, is in danger of being hijacked by a Republican Party that has suddenly fallen back in love with the idea of foreign policy. Having failed to resurrect Ronald Reagan’s spirit in their quest for the White House, Republicans have apparently concluded that the next best option is to resurrect Reagan’s enemy. Enter China, the new evil empire.

THE ONLY THING scarier than America’s general ignorance of foreign policy is the willingness of its political leadership to dive head-first into complex issues on a political whim. The China espionage case is a good example. The facts are clear: highly sensitive multiple nuclear warhead technology apparently was given to China by someone working at the Los Alamos laboratory in 1988. The Clinton administration discovered this in 1996 and now stands charged of not pursuing the case vigorously enough, in part, to protect its policy of “engagement” with the communist Chinese.

VIVE LA DIFFERENCE

Investigations and hearings clearly are warranted. Yet China in 1999 is not the Soviet Union of 1949. Given the heated rhetoric flying back and forth in Washington, it is worth thinking about the differences between the two:

The Soviet Union in 1949 was one of the most repressive societies the world had ever seen. Hundreds of thousands of people perished each year in slave labor camps. No economic or political dissent to Stalin’s rule was tolerated.

Meanwhile, Soviet intelligence forces were busy ensuring that the Eastern European states it liberated from Hitler’s armies would become a buffer zone of puppet states. Pledges to the West to hold free elections in Eastern Europe were brazenly violated. Soviet-backed communists in western Europe were strong; in Greece, Soviet aid fueled a vicious civil war. Most seriously of all, in China, Mao Zedong’s pro-Moscow Communists had won a long civil war. The Red Army had more tanks and troops than any other and its air force and navy was improving.

The bottom line in 1949: Communism appeared to be sweeping the planet, with a Soviet state growing in power at the lead. There appeared to be no redeeming qualities in the Soviet regime. The explosion of a Soviet A-bomb and the launch of Sputnik in the next decade would only exacerbate that fear.

China in 1999 is altogether a different story. Political dissent is dangerous, though seldom fatal, according to Amnesty International. The group’s 1998 report notes that 230,000 people were detained without trial in 280 “re-education through labor” centers throughout the country for minor offences including prostitution, swindling and “other activities disturbing social order.” Rough justice, to be sure. But similar numbers and more were regularly killed in Stalinist purges in the USSR.

Economically, however, the state has embraced capitalism, a process that has diluted the authority of the Chinese Communist Party and likely will threaten its hold on the state in the future. More importantly, Chinese labor activists, ethnic groups and democracy advocates are engaged in a very real struggle to change the state and have won concessions in the past several decades.

In world affairs, China is a midget compared with Stalin’s state, which after all, in 1945, had just rolled into Berlin, having played a major role in defeating Hitler. China’s army is the world’s largest, but it is technologically backward (and terribly vulnerable to western forces). Its air force and navy are even more out-classed.

And while China is a nuclear power, its arsenal is small and defensive in nature by any reasonable definition. (Ten years after allegedly stealing the secret of the U.S. M-88 “MIRV” multiple warhead, China has yet to deploy a single one.) China has some territorial disputes with its neighbors but except for Taiwan, none are considered a potential cause for war.

The bottom line in 1999: China’s future development is completely up for grabs, with hard-line elements involved in a protracted struggle with reformers. It appears certain the country will become more powerful economically and will inevitably seek to improve its military capabilities (and, by extension, its political influence). But the country will remain desperately poor well into the next century.

AMERICA’S STAKE

Viewed with any kind of perspective, the national interest in the China nuclear spy case appears to be clear. First and foremost, the United States should take no actions that will strengthen the hand of those opposed to political and economic reform in China. Second, ensure that U.S. security leaks are plugged and any spies punished. Third, prepare the United States for a “worst-case” outcome without making that outcome a fait accompli. That means continuing to maintain the U.S. military’s technological advantage on the battlefield and using that threat to deploy a defensive anti-missile system wisely as a bargaining chip rather than deploying it in a provocative manner.

Unfortunately, America’s political parties, and those who lead them, appear unable to conduct themselves in a manner consistent with the national interest. Each is so compromised right now — so in need of an absolute victory over its domestic political rival — that damage to the important long-term relationship between the United States and China is almost inevitable.

The Clinton administration’s China policy has gone from flip-flop to flop. From the campaign finance mess to the watering-down of technology controls and the loss of leverage on human rights policy, just about anything the administration proposes at this point can be reasonably questioned as either a cover-up or appeasement.

But as poorly implemented as Clinton’s China policy has been, it is at least based on a sound proposition: that China should not be isolated by economic or political sanctions and must be dealt with differently than, say, Iraq. Republicans appear to be veering dangerously toward anointing China an enemy, an action that would not only be premature, but counter-productive.

It will be up to the Republicans to take the high road. With an election coming, that’s not much on which to hang your hat.

Michael Moran is MSNBC’s International Editor