It’s been dubbed the “split-screen crisis:” air raids on the Iraqi capital on one side of your television screen, an impeachment battle in the American capital on the other. Did President Clinton hope his attack on Iraq would make half that screen go away? It is impossible to know. But it is also irrelevant. To paraphrase Britain’s Tony Blair’s comment about Saddam, how can anyone take the word of a “serial liar?”

Let's be fair. Despite what some of the less tactful Republicans in Congress might believe, the Iraq crisis is neither sudden nor manufactured. Relations between the U.S. and Iraq deteriorated to the brink of war in January; it happened again in November, and finally went over the edge this week. Honest people can agree or disagree on the role Clinton’s political problems played in the order to attack. But none doubt that one way or another, this week or next, U.S. forces were fated to tangle again with the Iraqi regime.

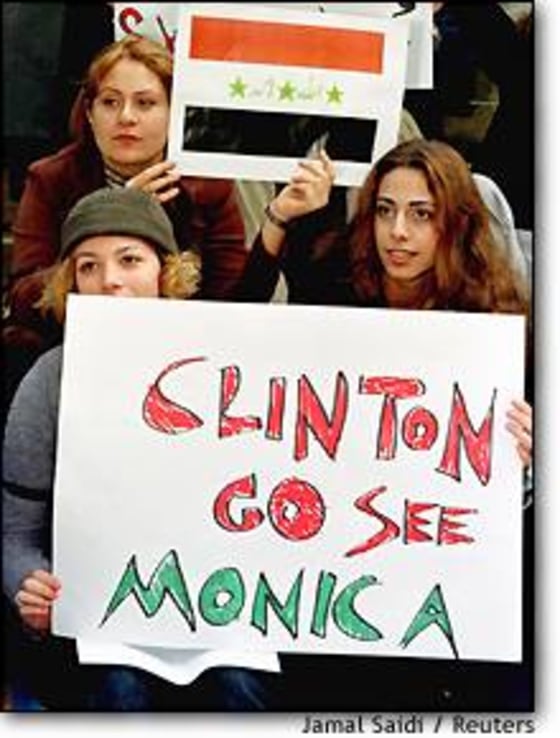

The White House argues that the timing is coincidental and under these circumstances, no one will be able to prove otherwise. Let’s concede the point. And let’s also concede, while were in the mood, that the American media’s obsession with the Monica Lewinsky scandal and all its related muck and mire may be contributing to the average person’s sense that Iraq has suddenly popped up out of nowhere at a suspiciously propitious time for Clinton.

PANTS ON FIRE

Credibility is the real issue here — the one that will linger when Saddam, Clinton and everyone they touched, gassed or slept with is gone. Not Clinton’s personal credibility, but the credibility of the American presidency. The question is not whether Clinton “wagged the dog.” That charge is revived just about every time a president makes a move abroad. The real question is why major world powers are not, this time, willing to dismiss the notion.

A French diplomat in Washington told me Friday his government is deeply disturbed by the timing. “It’s not a question of ‘Is he trying to change the subject.’ It’s the fact that he has no way to disprove it,” the diplomat said. “The appearances are terrible.”

But it goes deeper. Senior French officials have told their own press that they fear the United States is entering an ugly period in its history akin to the McCarthy period of the 1950s.

“When officials are being forced to admit their sex problems in public, this is crazy,” said the diplomat. “But it is crazier because it dominates the political talk. And this is the country that wants to remake NATO!”

It’s not just the sexually liberated French, either. The British, soldiering along in the Gulf with American forces, admit to concerns about the stability of the country on the other end of their “special relationship.”

A British diplomat attached to his country’s NATO delegation in Brussels — who, like the French diplomat, asked to remain nameless — said it’s not the impeachment-Iraq debate that is worrying most U.S. allies.

“It’s the sense that you have a president flailing in his death throes and a Congress that appears to be ready to ignore all other issues, no matter how pressing, for the sake of destroying the man.” In the long term, he said, “British officials, and Europe in general, [are] very concerned that what is happening in Washington is the launch of a permanent witch hunt that will cripple Clinton’s successor and the one who comes after him.”

EMPOWERING THE ENEMY

From a practical diplomatic standpoint, the United States can always write off Chinese, French and Russian objections as the rumblings of thin-skinned, somewhat resentful nations that are forced to face their own second-class status every time the United States flexes its muscles.

But there is something more serious about their objections this time around.

Russia withdrew its ambassador to the United States and Britain — an action it has not taken since well before the Soviet reformer Mikhail Gorbachev took power. China saw the attacks as precedent- setting. France attacked the U.N. report that is the basis of the air strikes. None of them mentioned Clinton’s domestic troubles. But in their media, the point came across loud and clear.

Analysts, former policymakers, America’s Arab allies and even some within the Clinton administration have been arguing for over a year that U.S. policy toward Iraq is in disarray. The policy has been mutating in an uncontrolled manner from one designed to ensure Iraqi compliance with U.N. disarmament resolutions to one based on military containment. Making this change while holding together the often fractious U.N. Security Council was difficult. Doing it with the president’s personal motives under question is, frankly, impossible.

CROCODILE TEARS

Consider what came before, the political reference points of today’s American electorate. The murky Kennedy assassination. The half-truths of the Vietnam War. The absence of truth — “No one is entitled to the truth,” as E. Howard Hunt said — of Watergate. The memory lapses of Iran-Contra. Of all presidents, Clinton, the first president of the scandal generation, cannot dare ask people not to be skeptical.

Yet the White House is indignant that the motives of a president who has admitted lying repeatedly to international television audiences should find his motives in doubt.

From Saddam Hussein’s promises of “unconditional compliance” to Clinton’s Monica denials, this is the age of the repeat offender. Ironically, at the precise moment that United States and Britain officially gave up on Saddam’s redemption, the U.S. political class appears to have given up on its president’s. The timing is more than Machiavellian. It’s positively cosmic.

As a man and as a president, Clinton is in a terrible position. As the great H.L. Mencken said, “It is hard to believe that a man is telling the truth when you know that you would lie if you were in his place.” That wouldn’t normally be a problem for the leader of the world’s last remaining superpower. But then, these are not normal times.

Michael Moran is MSNBC’s International Editor