Ever since Richard Nixon turned American foreign policy into his own personal escape capsule in the wake of Watergate, it has been assumed that presidents in trouble at home could escape by going abroad. But what worked for Nixon will not work for Bill Clinton. He may survive as president, but his days championing American values in the wider world are over.

When Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in 1974, much of the rest of the world was caught completely off guard. The charges against Nixon, viewed from outside the confines of the United States (or even the yet-to-be completed Beltway), looked unpleasant but not job-threatening. Only later did the extent of Nixon’s abuse of constitutional power — his attempt to use the CIA to thwart the Watergate investigation, for instance, or the details of his “hush money” bribes of the Watergate burglars — come fully to light.

From abroad, it looked very different. Nixon had recently been re-elected by a landslide. He had broken a taboo and opened relations with China. He had initiated a détente with the Soviet Union and, in between, had helped prevent Israel from being overrun by Syrian and Egyptian armies.

“I never understood Watergate and I don’t fully understand it to this day,” Leslie Stone, former chief commentator of the BBC, told me a few years back. “To us, it seemed as if you Americans had lost your minds. From a British standpoint, he was one of your greatest presidents.”

THE CREDIBILITY GAP

This is hardly true of Clinton today. Foreigners may not understand Americans’ puritanical insistence on investigating adultery, but they know a lie when the see one. Who signs treaties with a liar? Who risks domestic political unpopularity or economic hardship for the sake of a liar? (Hint: There’s one born every minute.)

Nixon’s sins arguably did more damage to U.S. political culture than any of the idiocies of the current administration. But Nixon never lost respect abroad. Watergate, complex and at the time “plausibly deniable,” did not prevent Nixon from sending the a message during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War that a nuclear war might result if the Soviets intervened.

In Moscow then, there was no question that Nixon’s NATO allies or the U.S. Congress would back Nixon’s threat. Can the same be said of Baghdad’s view of Clinton today?

To be fair, the Cold War led to a far more deferential treatment of U.S. presidents by Congress and America’s allies. But Clinton’s troubles with foreign policy long ago outgrew that excuse.

DEEPER THROAT

Just how deep is the hole in which the American commander-in-chief finds himself? Just look at the address to the Council on Foreign Relations he gave here Monday. Clinton laid out a series of goals for the United States during the rest of his term. Among them were:

Convince the new Russian government not to ditch painful market reforms from which few of its people have benefited.

Convince Japan to reform its teetering banking system, a goal tantamount to asking Tokyo to allow five of its top ten banks to go bankrupt.

Convince Congress to meet its commitment to the International Monetary Fund so that it can manage the global economic crisis that has put Russia on the mat and left Latin America and other developing markets staggering.

This is quite a list. And, it is not one likely to be accomplished by a president whose own political future is in doubt. Without the intense pressure that only a strong American president with strong congressional support can muster, it is difficult to imagine officials in Moscow or Tokyo willingly adopting serious austerity policies in the face of deep recession.

In fact, Clinton’s third stated goal — getting Congress to meet America’s commitment to the IMF — practically precludes the other two. Why, leaders in Tokyo and Moscow may ask, should we adopt austerity policies that will probably cost us our political heads when an America enjoying record economic performance won’t even fund the financial police agency meant to enforce the terms?

Clinton has gone from promising to pay Washington’s bill to the United Nations to begging Congress to make good on its IMF commitments. That is an astounding statement of the damage he has inflicted on himself, and ultimately, on American interests abroad.

FORGOTTEN, BUT NOT GONE

Beyond the economic issues Clinton addressed Monday, consider the laundry list of foreign policy “successes” he regularly reeled off during the 1996 campaign:

Peace in the Middle East: Not likely without a credible threat of U.S. pressure on Israel. Benjamin Netanyahu called that bluff in the spring even before Congress began building his political gallows.

The Dayton peace accord: Never popular among Republicans because of the 8,000 U.S. troops stuck there enforcing it, chances of its being renewed again next year look dim. Without the U.S. troops, NATO forces say they will pull out. Anyone want to bet how long Slobodan Milosevic will abide by Dayton afterward? It’s possible the next U.S. president may have to decide between bombing Serb forces in Kosovo, where they’re again on the offensive, or in Bosnia.

Disarming Iraq: On Monday, two days after the release of the Starr report, Iraq’s rubber-stamp parliament said it planned to end all cooperation with UNSCOM, the U.N. inspection team that enforces the Gulf War cease-fire provisions. With the Gulf coalition weaker than ever, the United States is said to be considering a complete review of the postwar terms imposed on Iraq as a way out of the cyclical confrontations with Baghdad. No one pretends such a move would leave Iraq thoroughly disarmed.

The North Korean nuclear deal: A few days after Clinton’s first “apology” to the nation for lying about his relationship, North Korea launched a two-stage rocket over Japan. The country has threatened repeatedly to pull out of a 1994 deal trading western nuclear power technology for a complete freeze in North Korea’s nuclear weapons development program. Always a risky proposition and bitterly criticized by most Republicans as unenforceable, the North Korean deal now looks unlikely to survive the year.

What’s left? Haiti. The bailout of Mexico in 1994. And Northern Ireland.

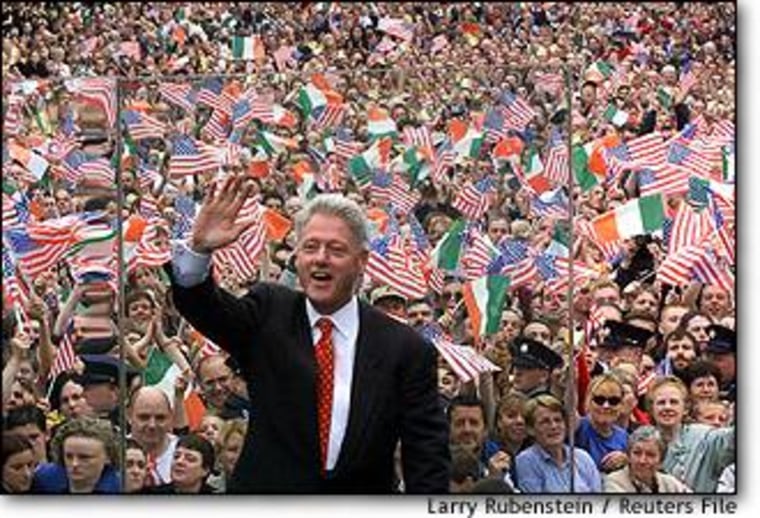

Northern Ireland, an issue of great interest to many Irish-Americans but of little national security consequence, may turn out to be Clinton’s greatest accomplishment abroad. He deserves the credit he gets for helping legitimize Sinn Fein’s Gerry Adams as a negotiating partner with the British. London and most of the State Department opposed it. Clinton insisted and was right to do so.

But Clinton’s already made his trip to Ireland and Lord knows he need not make another visit to the Blarney Stone.

To the end of his term, and indeed his life, Nixon risked jeers and ridicule to add his voice to the public debate and champion what used to be called “the American system,” a system that rightly drove him into retirement. To the end of his days, Nixon was accorded a statesman’s welcome on trips abroad. He was a scoundrel, but he was a scoundrel with a message. The only message Bill Clinton now bears to the rest of the world only confirms the planet’s worst fears about modern, superficial America.

Michael Moran is MSNBC’s International Editor.