The CIA’s conclusion that Saddam Hussein likely did record the recent audiotape exhorting “heroic resistance fighters” to battle U.S. and British occupation troops increases pressure on the U.S. military to launch another high-profile manhunt even as efforts to capture al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden falter. While both could soon be captured, history is discouraging, as similar such missions bedeviled U.S. presidents throughout the 20th century, whether the targets were Mexican banditos, Somali warlords or exiled Saudi billionaires.

The Bush administration, as it did in regard to bin Laden in the months following the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, has tried to downplay the significance of capturing Saddam, stressing instead the creation of a stable and secure environment in Iraq. On the eve of al Jazeera’s broadcast of the Saddam tape, recorded via telephone by the Arab satellite network, the administration continued to be circumspect about Saddam’s fate.

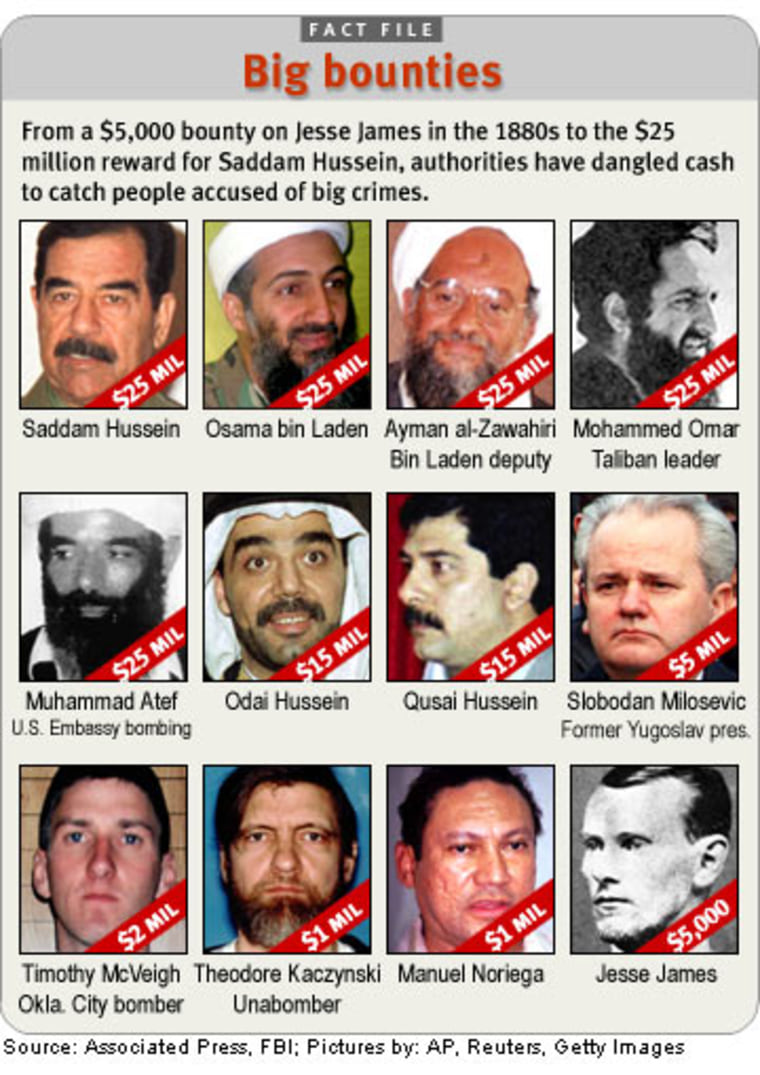

“We believe it’s important to do everything we can to determine his whereabouts, whether he is alive or dead, in order to assist in stabilizing the situation and letting the people of Baghdad be absolutely sure that he’s not coming back,” Secretary of State Colin Powell said July 3 as the United States announced a $25 million reward for information on the whereabouts of the deposed Iraqi despot. “And this is just another tool to be used for that purpose.”

With U.S. intelligence basically authenticating the audiotape of Saddam urging resistance, however, many believe it no longer is possible to separate the capture of Saddam and the deadly attacks directed at U.S. forces on a daily basis.

Saddam has become “a rallying point for all of these different groups who would like to regain power to conduct these operations,” says Rick Francona, a former U.S. defense attaché in Baghdad and later a U.S. intelligence agent. Francona, who has written extensively on Saddam’s regime, says the Iraqi leader’s continued presence in the country is an inspiration to “a nascent resistance organization that could blossom into a much wider, broader problem for the United States.”

WILL MONEY TALK?

The reward money, and $15 million each being offered for the heads of Saddam’s sons Odai and Qusai, may well prove vital. But similar bounties offered in the past on such notorious figures as bin Laden, Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar and the Somali warlord Mohammed Farah Aidid failed to flush the prey. Nor has this tack helped to apprehend Imad Mugniyah, the suspected author of the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon, and founder of Hizballah, still regarded by most U.S. counter-intelligence agencies as the most dangerous and well-trained terrorist group in the world.

Unfortunately for Washington, the history of military-led efforts to “decapitate” foreign enemies is not encouraging. From the apparent failure of the air strikes directed against Saddam in Baghdad this year to the millions of dollars worth of Tomahawk missiles shot at bin Laden’s al-Qaida bases in 1998 and again in 2001, history suggests that it is supremely difficult to take out a foreign enemy’s leader or even a top military commander without first completely defeating that country’s military on the battlefield.

One of the rare successes, the capture of Panamanian dictator and alleged drug kingpin Manuel Noriega in 1989, required an invasion by 25,000 U.S. troops and four days of door-to-door searches. That in a country broadly sympathetic and intimately familiar to the United States.

But even the unilateral surrender of an enemy does not guarantee success. When Germany surrendered in May 1945, the fate of Adolf Hilter remained inconclusive for decades, until the early 1990s, when the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union admitted it had taken Hitler’s body from the infamous Berlin bunker, which sat inaccessible to scholars in the no man’s land between East and West Germany throughout the Cold War. This left Western scholars at a loss to physically prove Hitler’s death, and well into the 1970s rumors of Hitler’s purported escape to South American persisted.

COMBING MOGADISHU

Besides the ongoing hunt for bin Laden, concentrated primarily in the northern tribal reaches of Pakistan, the most recent instance of a full-blown military manhunt is the 1993 effort to capture troublesome Somali warlord Aidid.

Frustrated by Aidid’s unwillingness to heed the U.S.-installed United Nations command in the East African country, the United States placed a $25,000 bounty on him. When that failed, U.S. Army Rangers launched a raid aimed at killing or capturing the warlord. But the raid went badly awry and ultimately left 18 U.S. soldiers and some 500 Somalis dead.

The disaster led to the collapse of the U.S. mission in Somalia, which quickly sank into a period of anarchy that has been exploited by stateless terrorist groups, including al-Qaida. Aidid died in 1996 in a gun battle with rival Somali forces.

Military historians, prone to reach further back, cite the 1916 manhunt for Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa as their cautionary tale of choice. That year, with Europe aflame and the United States, as usual, late to the European party, the U.S. Army was ordered into Mexico to find the famous marauder after Villa’s men raided the border town of Columbus, N.M., and executed 17 Americans.

The manhunt, led by an Army cavalry division, was an enormous failure, and the United States withdrew in 1917 after suffering 24 dead. The only solace, retrospectively, was that the action provided much-needed field experience for two men who would go on to fight in Europe in World War I — Brig. Gen. Jack Pershing, and a head-strong young lieutenant named George S. Patton.

Still, historians note that at a time when the United States should have been preparing for - or even fighting - World War I, it was chasing a Mexican rebel through the arid Sierra Madre.

A FEW NOTABLE EXCEPTIONS

While military manhunts rarely have been fruitful, that is not a rule. Over the years, on a few occasions, extraordinary victories have been notched. Overkill aside, the capture of Noriega certainly falls into this category.

There are others. In 1993, the United States finally prevailed against a shadowy foe also subject to an American bounty: the head of the Medellin cocaine cartel, Pablo Escobar. He died in a gun battle after years of being tracked by U.S. intelligence, though, in keeping with those less dangerous times, the United States refused to take any credit for his demise.

During World War II, an intelligence breakthrough helped America find the commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy and architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto. In 1943, U.S. code breakers discovered the admiral would be flying aboard a Japanese bomber near the Solomon Islands, where U.S. fighters ambushed and killed him.

Another similar success beckoned in 1985, when a national security aide to Ronald Reagan, Oliver North, saw a chance to “pull a Yamamoto,” as he would eventually describe it to U.S. Senate investigators.

U.S. intelligence discovered that Egypt was concealing the whereabouts of the Palestinian terrorist Abul Abbas, the mastermind of the hijacking of the Italian ocean liner Achille Lauro, which included the murder of a wheelchair-bound Jewish American named Leon Klinghoffer.

Acting on that intelligence, North sent U.S. Navy interceptors to force the Egypt Air 737 carrying Abbas to land at a NATO air base in Sicily. Abbas was handed over to Italian authorities for prosecution. But even this effort went awry. Finding insufficient evidence that he had carried out the attacks, the Italian court released Abbas, who quickly fled to the bosom of one Saddam Hussein (ironically, then a major recipient of U.S. foreign aid). In a final irony, Abbas was apprehended by U.S. troops in April in as they swept through Baghdad. While his capture was a welcomed event, Washington would gladly trade him, and $25 million in cold, hard cash, for a certain native of Tikrit.

Michael Moran is an MSNBC.com senior correspondent.