In the Yangtze Valley of central China, the water is rising behind one of the world’s largest dams, creating a reservoir that will eventually force more than a million peasants to leave their ancestral homes. The deserted villages in the path of Three Gorges flooding are to some eyes a wasteland, but to some Americans there is history in those villages that money can buy.

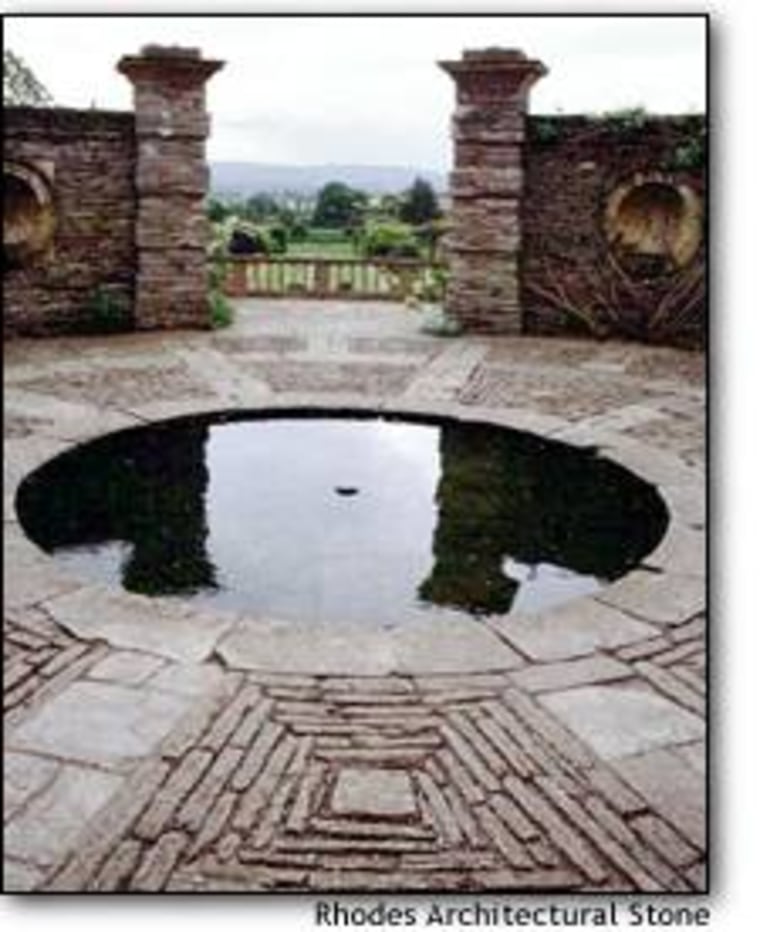

Master stone mason and entrepreneur Richard Rhodes has built a $10 million business from a simple supply-and-demand equation.

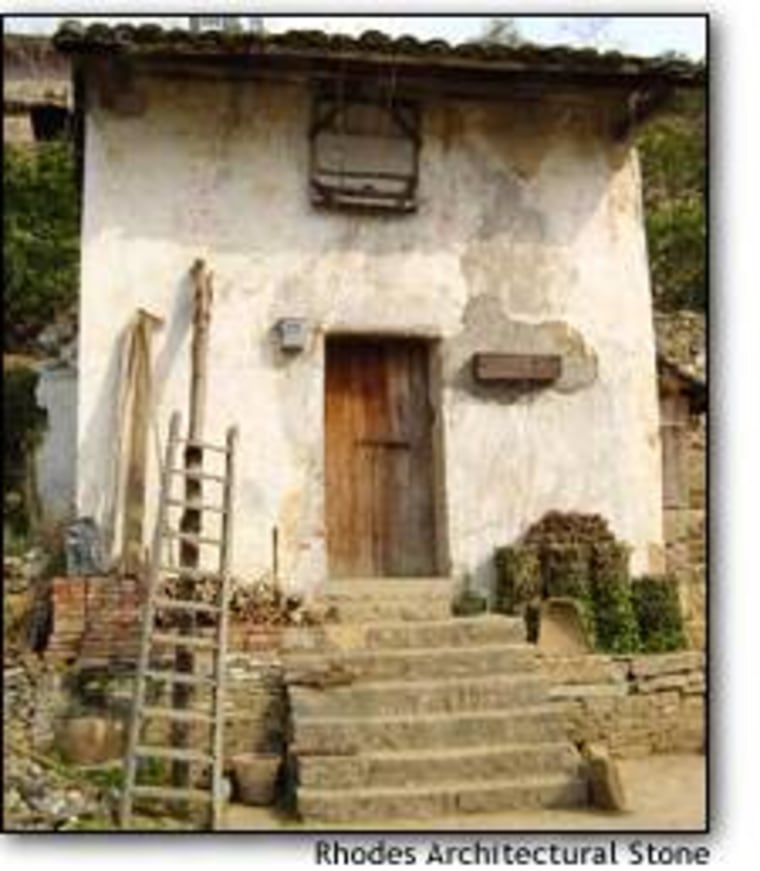

The Three Gorges reservoir is expected to flood an area larger than Los Angeles, inundating 1,600 to 1,700 villages. To the Chinese government, these old homes, many of them with the most basic of facilities and dirt floors, are obstacles in the way of development. Some are slated not just for submersion, but also for demolition to make way for shipping lanes.

But to well-heeled clients in the United States, the stone in these buildings — some of them hundreds of years old — is a treasure. “In our country, our buildings, especially on the West coast, which is 100 years old ... there is an aching for history, or longing for it, says Rhodes. “We want so much to find things that have some sort of resonance. And these stones have it. They have a life.”

Province of the wealthy

Only generations of footsteps and centuries of weather can create the patina on the Chinese stones that Rhodes imports — and only the wealthy can afford it. Rhodes cannot discuss most of his clients, but says many are “household names.” But the list of those who don’t mind being named includes talk show host Oprah Winfrey and stockbroker-turned-purveyor-of-good-taste Martha Stewart, who has also featured Rhodes on her television program.

Rhodes Architectural Stone has a contract to build entirely from antique Yangtze stone a 40,000 square foot mansion in Greenwich, Conn., for financier Steve Steinman, a prominent player on Wall Street.

The project, which he believes is one of the largest stone residences in the country, will require 200 shipping containers of shop-drawn, handcrafted antique stone — about 4,000 metric tons.

Rhodes won’t reveal the value of the contract, but his prices posted on Rhodes’ Web site begin to suggest its magnitude: One cubic foot of antique Chinese limestone is listed at $140.

Rhodes stonework has been featured in Architectural Digest, House and Garden Magazine, Beautiful Homes, Estates West.

The brainstorm came in 1998. Rhodes was already in China, working on a project for “an extraordinary client” who was building a replica of a 15th century Japanese palace in Woodside, Calif. (That client has been reported to be Oracle founder and billionaire Larry Ellison. Rhodes does not confirm these reports.)

The contract was massive — for a 16-foot wall that would form the foundation, moat and bridges for the structure, and the client wanted to use Chinese stone. It was big enough to justify setting up a factory in China, and training Chinese masons in the methods Rhodes had studied in Europe. The stones were cut and shaped prior to shipping, thus cutting down on shipping costs.

On a visit to the construction site for the Three Gorges Dam in 1998, Rhodes realized there was a gold mine there — tons of antique material in the path of the hydroelectric project.

Whereas he had used salvaged material out of Italy and France in the past, it would take years sometimes to cobble together enough of one type of material for a large project. “There wasn’t a business there,” said Rhodes. But the volume of ancient material made available by this single Chinese construction site was mind-boggling. “China is where I had the ‘aha,’” says Rhodes, “when I went there to the dam and realized that all those villages were going to be under water and lost.”

By leveraging the California contract, he began negotiating deals in the Three Gorges to salvage stone from villages. Rhodes Architectural Stone now cuts antique stone for export at eight factories. He estimates that the company has salvaged and shipped 16 to 17 villages’ worth of antique material for projects in the United States.

With China as a springboard, Rhodes has started working in other parts of the developing world. In India, the company salvages stone from buildings damaged or destroyed in the Gujarat earthquake two years ago. It offers material from elsewhere in Asia and North Africa, and is exploring sites in South America. In China’s capital, Beijing, hundreds of blocks of traditional homes have been demolished to make way for the 2008 Olympic Games.

“We tell the story about the gorge — that’s where we started — but its really a global stone company at this point, because we realized that there are antique stone resources being demolished for all kinds of reasons — good and bad — around the world and we’re trying to rescue the materials,” says Rhodes.

THREE GORGES QUESTIONS

From the point of view of a mason and businessman, it’s the arbitrage opportunity of a lifetime.

But being connected to the Three Gorges project, however tangentially, always draws criticism. Damming the massive Yangtze river, for flood control and power generation, was first raised by Sun Yatsen early in the century, but logistics and politics prevented it for decades. It was only in 1992 that it was pushed through the National People’s Congress, despite unprecedented opposition in the body, with the strong backing of then-Premier Li Peng. International critics, and some vocal Chinese see the dam as a monumental boondoggle that will cause irreparable environmental and social problems.

The forced resettlement of at least 1.2 million peasants from the project area has been the most controversial aspect of the project. From the start, there has been documentation of regional officials embezzling the funds earmarked for new homes — corruption that has been acknowledged by the central government. Some of the peasants who have led opposition to the project or its handling are in jail for speaking out.

Water began filling the reservoir June 1. The entire project is slated for completion in 2009.

Doris Shen of the International Rivers Network urges international companies and lenders: “Stay away from the project. If you’ve been involved, lean on (local) government officials to treat the farmers in accordance with human rights standards.”

She argues that since China is still taking bids for the later stages of the project, it is not yet a fait accompli, and the world can bring pressure to bear, including smaller companies like Rhodes. Berkeley-based IRN is a longtime critic of the dam on environmental and human rights grounds.

“Companies are profiting from the dismantling and destruction of the villages,” Shen says.

Another watchdog group, Canada-based Probe International said it had looked into Rhodes’ business and concluded that it was largely positive, or did not at any rate contribute to what they see as the “tragedy” of the Three Gorges project.

‘MAKING LEMONADE’

Rhodes argues that his company is saving antique material, which he notes is beautiful, but not historically significant archeological artifacts. He also provides jobs in an area that has suffers chronic unemployment. Locals are employed for three to six months to dismantle the doomed villages and load the stone onto barges for its voyage down river. Rhodes estimates 600 people are also employed cutting the company’s stone before it leaves China.

Because the U.S. firm is interested only in the top three to four inches of the stone, the portion that remains is donated back to China for construction above the new waterline.

When possible, Rhodes compensates former residents of the dismantled homes, but doing business in the evolving communist system is complicated — ownership is poorly defined.

“In the end, we tried to take the most realistic approach, which was that we had to pay everybody something. The government, the military, the local party officials, and if we could determine that your family lived in this particular building, we compensated those people also,” he says.

He is aware of the controversy over the Three Gorges Dam, but not apologetic for his role in the area.

“There are people out there that have a different view, but I think no matter where you stand — whether you think the dam is a good thing, or the dam is a bad thing — the dam is a fact, and the water is rising,” says Rhodes. “If we can make lemonade out of the situation — if we can take beautiful things, prevent part of the world’s patrimony from going to the landfill, that’s just common sense to me.”