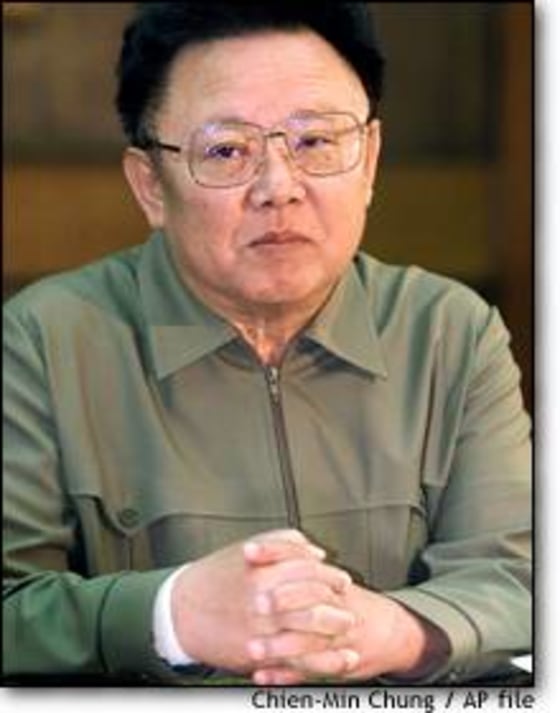

North Korea’s persistent saber rattling and leader Kim Jong Il’s threat that his communist regime may export the nuclear capability it is now openly pursuing beg the question of what concrete steps, short of war, the United States and its allies can take in response. Indeed, the issue tops the agenda for Friday’s meeting between President Bush and Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi at Bush’s Texas ranch.

The White House has tried name-calling, ignoring Pyongyang and stalling, but the North Korea problem has not gone away. In Washington, a growing chorus of policy experts is calling for urgent action to halt that process. There’s growing support for punitive measures, but in some quarters they are seen as a last resort.

The Bush administration has said it seeks a “diplomatic solution” to tensions on the Korean Peninsula, but its approach has been erratic — a product, observers say, of a divide between administration hawks and doves.

While one camp favors economic strangulation, the other favors talks.

“President Bush has apparently chosen so far to effectively follow a policy of isolation, punctuated by occasional, mostly fruitless meetings with the North,” says a major task force report “Meeting the North Korean Nuclear Challenge,” published by the Council on Foreign Relations this week. The end result: Not only has Pyongyang’s apparent resolve to pursue a nuclear program hardened, but it has had time to push the program ahead. In its most serious threat, made at talks hosted by Beijing, North Korea said it not only has fissile material, but may decide to sell it abroad.

As North Korea’s nuclear claims have grown, a new consensus is taking shape among experts and policymakers in and outside the White House. Hard-liners, who have argued that negotiating with Kim Jong Il’s Stalinist regime would be caving in to “nuclear blackmail” are coming to the view that serious talks likely are necessary if only to justify harsher actions later, and win support of key allies.

Meanwhile, a growing number of moderates are beginning to concede that punitive economic measures — possibly even a naval blockade — may be needed to force North Korea to back down.

“Without negotiations, it is diplomatically impossible to take any of the tougher actions you might want to take,” says Marcus Noland, senior fellow at the International Institute of Economics. “All actions require at the minimum acquiescence of U.S. allies in the region.” While there is dwindling hope that talks with North Korea will succeed, he says, it’s the only way demonstrate to China, Japan and South Korea that the U.S. has made a good-faith effort.

In the spotlight: What “tougher actions” would be effective? What can be done in lieu of a military attack to inflict pain on a country whose economy is already so broken?

Little to sell

As it is, North Korea has little to export, and the United States already has at least a dozen laws restricting commercial transactions with it. U.S. efforts also keep North Korea cut off from lending by international institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

One common theme is now recurrent: Cutting two of the mainstays of the North Korean economy — missile exports and illegal drug trafficking, which together generate roughly one-half of North Korea’s hard currency — could deal a serious blow to the country’s pursuit of nuclear weapons.

Sales of North Korea’s missiles, developed from a combination of Russian and Chinese Cold War era technology, raise about $560 million a year for the regime, the U.S. military estimates.

How to stop the trade, however, is unclear, and different strategies have very different political implications. Most effective, but more politically problematic would be a naval blockade.

But Pyongyang is not among the 32 signatories of the Missile Technology Control Regime so these sales do not violate international treaties. For now, the United States is using its considerable clout to lean on known customers — such as Egypt and Pakistan — to halt deals that would help fuel the regime.

That means a unilateral attempt to blockade North Korea, a strategy that has been mooted by some hard-liners, runs up against international law.

Even the more moderate policy experts at the Council on Foreign Relations say that a blockade would be worth considering if negotiations fail.

But they maintain that the effort would require support of key players in Asia — China, South Korea and Japan who so far balk at such an aggressive measure — or a U.N. resolution expressing approval for ship interdiction.

Pyongyang, for its part, has said that interdiction of its ships would be seen as an act of war.

In what was perhaps a test balloon for this idea earlier this year, Spain boarded a North Korean ship carrying missiles bound for Yemen. But the Spanish, who had acted on U.S. intelligence, ultimately turned over the ship and its cargo to Yemen, which argued that it had legitimately paid for and owned the missiles.

Drugs and suitcases of cash

Australia’s recent discovery of a heroin shipment involving North Korea couriers was yet another reminder that a major source of hard currency for North Korea — in a trade that is apparently conducted by regime officials — it the sale of illicit drugs, worth an estimated $100 million a year. A similar amount is believed to be generated by printing counterfeit money, mostly U.S. $100 bills.

Beefing up existing drug interdiction programs could well be part of this week’s summit between Bush and Koizumi.

Pyongyang has been known to produce and export heroin, and in more recent years it also has been manufacturing methamphetamines, most of which is believed destined for the lucrative Japanese market.

Another common theme among policymakers is this: China has to do more to help bring North Korea to heel.

The old relationship between these communist comrades has long since broken down, and most Asia experts say Beijing is mortified by the idea of a nuclear-armed North Korea.

China's fears

But China is also afraid of a collapse in the neighboring country, which would likely send many thousands more refugees across its border.

Possibly the single most punishing measure could come from Beijing cutting off oil supplies to North Korea, where industry and agriculture are already seriously hobbled by a shortage.

After U.S. envoy James Kelly disclosed in October that North Korea had admitted to a uranium enrichment program, the United States and allies in the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization stopped fuel shipments to North Korea, which had been provided under a 1994 agreement, leaving North Korea even more dependent on Beijing.

“If you could get the Chinese to cut off oil — if there were one action that could really affect (North Korea’s) ability to function at all, that would be it,” says Eric Heginbotham, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, and director of North Korea task force.

Will China close the tap? In a sign that it was beginning to take a more active role in solving the problem, Beijing reportedly did shut down a pipeline carrying oil across the Chinese border for three days, Western diplomats say, to force Pyongyang to join talks with the United States in Beijing.

Hardening positions

It was not the only sign that U.S. allies might be taking a harder view of North Korea.

After Kelly’s revelation last October, Tokyo halted a process of negotiations aimed at normalizing ties with Pyongyang, which would have included a massive economic aid package.

At the same time, Tokyo has quietly tightened the screws on money flowing to North Korea from Japanese nationals of ethnic Korean background who profess loyalty to Pyongyang — some 600,000 to 700,000 people. Although these remittances are not illegal, one bank used as the conduit for much of the money went belly up after years of funneling “loans” to North Korea that were never paid back. The government took it over, and ended the practice.

Food question

One of the most difficult questions is whether food aid should be used as a tool to punish Pyongyang. The country is now dependent on the outside for as much as one-third of its total supply.

In addition to food aid provided through the U.N.’s World Food Program, through which the United States is the largest donor, it is unclear how much aid is provided by China or South Korea.

Even some of its stunning diplomatic success with Pyongyang under former President Kim Dae-jung’s sunshine policy was apparently achieved with massive under-the-table payments to Pyongyang.

An investigation of the allegations that the 2001 summit between Seoul’s Kim and North Korean leader Kim Jong Il was paid for suggest that those who favor aid to the North are losing ground. In addition, says American Enterprise Institute’s Eberstadt, the assembly is in the hands of the current president’s opponents, who oppose subsidies. “The message at the moment is that more foreign aid is a hard sell,” he says.

For Seoul, just 40 miles from the border with North Korea, and its massive buildup of forces, the calculation is a difficult one. Should it continue to court the regime in Pyongyang in the hope for gradual reform, a strategy that imperils its close security with the United States? Should it go along with U.S. efforts to squeeze North Korea — efforts that could trigger famine in the North, or spark a conflict that would put South Koreans on the front lines?