Lost in the shuffle between the war in Afghanistan, and the start of the war in Iraq was this news story: Two American teachers and a local colleague were gunned down in an Indonesian jungle. From the start, it was apparent that it was not a random act of violence. But the case, which entangles an American gold mining company, guerrillas fighting for the independence of Papua and the Indonesian military remains officially unsolved. Its implications still resonate on Capitol Hill, raising questions about Indonesia policy and the war on terrorism.

On Aug. 31, 2002, a group of international schoolteachers and family members were traveling on a remote road in Timika, Papua, near the copper and gold mines of their employer, U.S.-based Freeport-McMoran, when unidentified gunmen ambushed them in their vehicles. Hundreds of rounds and 45 minutes later, three people were dead — two Americans and an Indonesian — and 10 others in the party were injured.

The question of who did it goes right to the heart of Indonesia’s deepest political troubles, and raises questions about U.S. policy toward the island nation in the southern Pacific. Washington has long seen Indonesia as an important strategic ally in Asia because of its location, straddling key shipping lanes between Asia and the West, and its population of more than 230 million, mostly moderate Muslims.

The war on terrorism gave the Bush administration new incentive to be involved in Indonesia. The country’s military and police were again essential partners, after most of a decade at arms length, for their widely documented human rights abuses throughout the country. The October 2002 bombing of a nightclub in Bali that killed at least 200 people suggested that affiliates of the terror network al-Qaida, if not al-Qaida itself, had roots in Indonesia, prompting an expansion of the U.S.-Indonesian security partnership.

But as the triple-slaying case in Papua illustrates, it is often not clear whether Indonesia’s military is a force that promotes stability or undermines it.

Military officials immediately accused rebels who are fighting for the independence of the area, West Papua, from central rule by Jakarta. Papuan rights advocates said the military itself organized the attack — and had accused the Papuans in order to justify their own role in the region as security providers. An initial Indonesian police investigation also pointed to military involvement.

Louisiana-based Freeport-McMoran and Freeport Indonesia, for their part, issued press statements that they “deplore this senseless act of violence” but then fell silent, noting that the investigation was in the hands of the FBI. To this day, the probe is still pending.

“The preponderance of evidence,” according to a high-level U.S. State Department official, implicates “elements of the Indonesian army.” But, continued Matthew Daley of the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, during testimony before the House International Relations Committee in March, “we cannot make any definitive judgments until the investigative process is complete.”

High stakes

Just the implication that the military was involved raises awkward issues for the Indonesian government, the U.S. government, and for Freeport.

Indonesia wrested control of Papua from the Dutch in 1963. The United Nations sanctioned the move six years later in a vote by hand-picked local representatives. Although the vote was called an “act of free choice” it has since been widely disputed by rights activists. In the late 1960s, under then-military backed President Suharto, the military was charged with security for what was dubbed a “vital national asset.” Indeed, Freeport’s Grasberg mine alone has deposits worth some $40 billion. Freeport turns over 80 percent of its profits to Jakarta, making it the country’s single largest taxpayer.

Military security has been costly for Freeport, both in monetary and public relations terms.

Since the end of Suharto’s iron-fisted rule in 1998, Papuans and other political activists have openly challenged the Indonesian government, and the military role in Papua, where armed forces have been accused of hundreds of abuses and murders.

Papuan activists, representing some of the world’s most isolated indigenous people, and some of the world’s poorest, have been lobbying hard for the rights to the land and control of its resources.

Freeport’s 2002 company report says it paid $17.1 million for security, $10 million of it for “internal security” and $7 million in fees for the police and military.

There have been beefy one-time costs as well as the annual payments. Following riots by local Papuans in 1996, the company paid $35 million to beef up facilities for a security force that grew to 2,000 from 200 previously.

Core problem

A new report published under the Council on Foreign Relations says the military, and its lack of reform since Suharto’s fall in 1998, is at the core of tensions in Papua, and likely behind last August’s shooting.

According to “Peace and Progress in Papua,” put together by an Indonesia Commission made up of diplomatic, political and U.S. military experts on Indonesia, the military gets only 25 to 30 percent of its operating budget from the Indonesian government. The remaining 70 percent of its vast budget is raised through sanctioned operations, including security fees from Freeport and companies in resource rich rich Aceh, as well as illegal activities such as unapproved logging and mining, and running prostitution.

Its widely known abuses of its power further fuel separatist tendencies, the report says.

The commission urges multinational companies like Freeport to “gradually phase out their security service contracts with the military, as changes in the law permit,” and for the Indonesian government to withdraw the military’s much-feared special forces from the region.

It also urges follow-through on a law passed last year, under which 80 percent of the proceeds of the region’s natural resources should go directly to local Papuan administration, far more than currently remains in the province. To date, the law has not been implemented.

Freeport, long derided by rights groups for its unholy contract with the armed forces, has in recent years clearly tried to distance itself from alleged abuses by the Indonesian military — by setting up educational and social programs, and dedicating more funding to local Papuan communities. Publicly, the company remains neutral on political issues, and defers to Jakarta on security.

“In all countries, governments provide for the fundamental security for people living there and bus operating there, and just as other citizens and businesses in Indonesia, we rely on the government of Indonesia for the security of people, and government decides how to do that,” says company spokesman William Collier.

Anecdotally, the line between security and extortion seems to get ever more blurred.

According to one source close to the company, in the months prior to the Timika shootings, Freeport had been planning to hire a third-party security force to prevent the theft of gold concentrate, which the military was suspected of pilfering and secretly refining.

For Freeport-McMoran to extricate itself from its relationship with the military could be “a very dangerous process,” says Brigham Golden, a Columbia University anthropologist who has been researching the company for 10 years. He notes, there would have to be reform within Freeport, because people on staff also have “complex relationships with the military.”

Newer companies on the scene, such as British Petroleum, which has recently gained oil exploration rights off the Papuan coast, are determined not to be caught in the military web.

“They have the wonderful idea about society-based security assistance,” says Octavius Mote, a scholar at Yale University and rights activist. “We don’t know if they will be effective or not.”

U.S. policy

According to the U.S. State Department’s Daley, resolving the Timika murder case is “one of the most important issues of concern in our bilateral relationships with Indonesia.”

“We have made it clear to the government of Indonesia that those responsible must be identified and punished,” he said in his March Senate testimony, adding that an FBI team was returning to the scene to continue its probe.

The findings could call into question the resumption of military ties, under the IMET program (International Military Education and Training Program), which specifies non-lethal sales and training to its forces.

The United States resumed this program with Indonesia’s police and armed forces — long on ice because of U.S. displeasure with the Indonesian military’s human rights abuses in East Timor and elsewhere in the archipelago — in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

The argument used by IMET proponents was that helping to make the armed forces more professional would promote reform and democracy.

But this month, a group of 17 U.S. senators led by Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., wrote a letter to Indonesian President Megawati Sukarnoputri complaining that the second round of the joint military and police investigation with the U.S. FBI had “stalled.” Some $400,000 in funding for the the military training program is on hold.

Jakarta's jam

How to curb a military that has built up its own power and interests is an open question in Jakarta.

Plans to remove the military from politics have slowed to a crawl.

Despite calls for the military to give up its political role, newly proposed legislation shows there is a powerful effort afoot to claw back that role. Among other powers, the bill would give the military unilateral authority to deploy troops in case of an emergency, and only inform the president 24 hours later.

Ominously, in Aceh, the military this week declared martial law and launched a full-scale assault on separatist forces after efforts to salvage an autonomy deal broke down. What happens in that conflict is carefully watched in Papua, with similar claims to resources and autonomy.

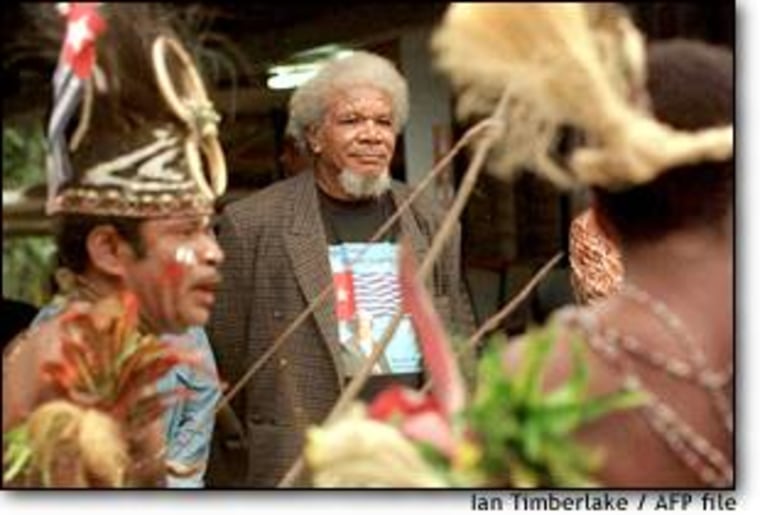

In Papua, there appeared to be the promise of change when seven special forces soldiers were tried for the 2001 murder of Papuan separatist leader Theys Eluay, who headed the Papua Presidium Council seeking the peaceful secession of Papua. But upon conviction this year, the toughest sentence imposed was under four years.